Issue:

March 2024 | Letter from Hokkaido

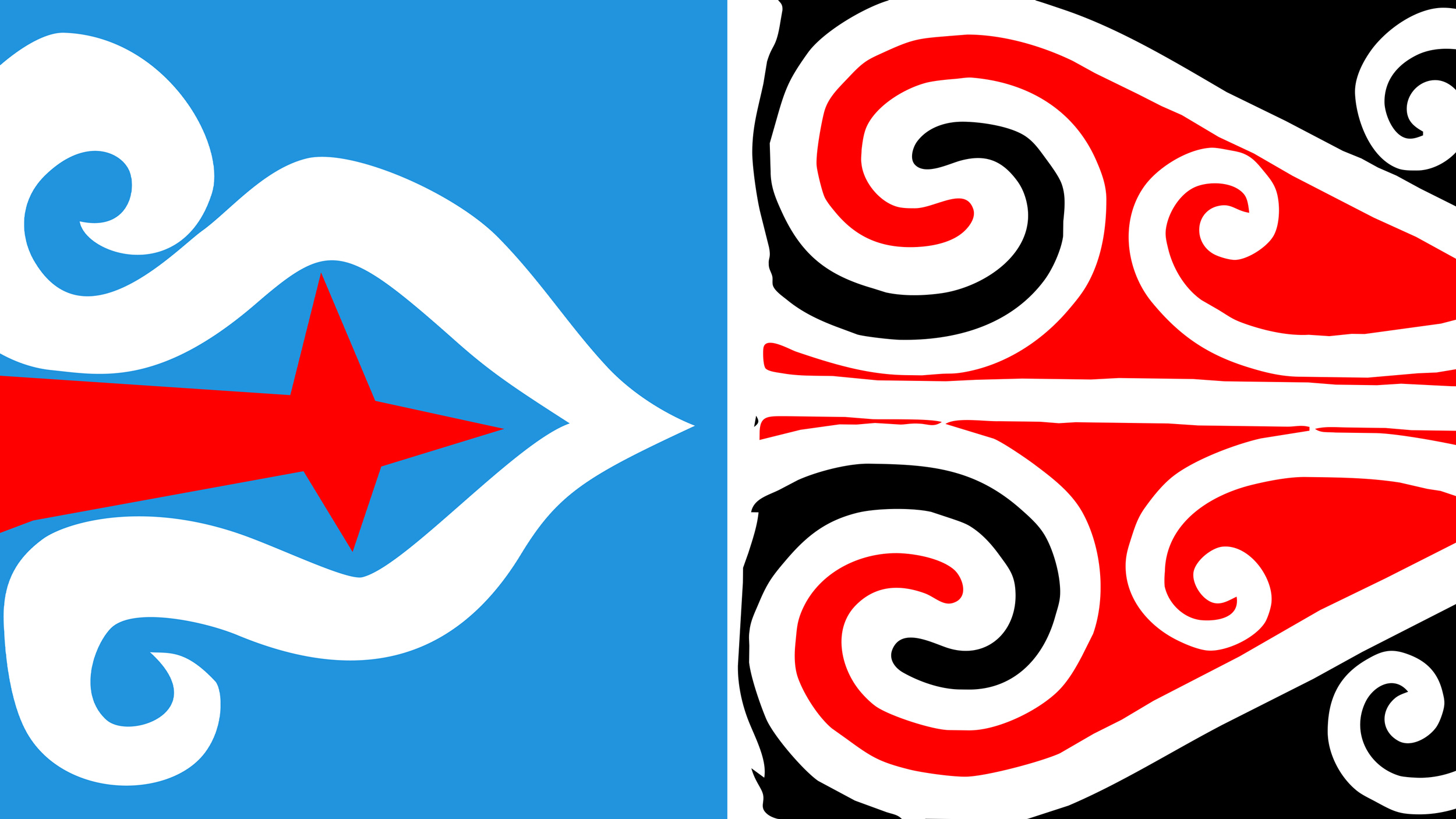

Exchanges between Ainu and Maori groups underline challenges facing all indigenous peoples

February is one of the busiest months of the year in Hokkaido, with the annual Sapporo Snow Festival and the slopes of Niseko drawing people from all over Japan and the world.

Recent visitors included a group of Maori representatives, who stayed at the homes of members of Nibutani’s Ainu community.

This area, a few hours by car from Chitose airport, is leading the way in Hokkaido in promoting exchanges with other indigenous peoples, along with more adventurous tourists seeking views of Ainu history and culture that are not welcome among official Japan’s nationalist circles.

The dozen or so Maori delegates who visited Hokkaido are from different areas of Aotearoa (the Maori name for New Zealand). They were members of Rangaranga Ltd., an indigenous organization that promotes international exchanges with other indigenous peoples. In addition to learning about each other’s language, customs, beliefs, and culture, Rangaranga places a strong emphasis on the concept of self-determination, or mana motuhake – a message they shared with the Nibutani Ainu.

The group’s visit was one of many exchanges between the Ainu and the Maori that have been held in both countries. It also came 100 years after the first recorded contact between the two peoples. In 1924, Tāhupotiki Wiremu Rātana, a Maori leader who founded the Rātana Church, a religious and political movement, travelled to Britain with a group of nearly 40 Maori to petition King George V to return confiscated Maori land.

He was denied a meeting, so his group then went to Geneva to appeal to the League of Nations, an effort that also failed. Having no choice but to make their way home, they travelled via Asia, stopping off in Japan. There, they encountered people of Ainu heritage, and the seeds for future exchanges were planted.

A century later, the Maori and the Ainu continue to struggle for their rights and against discrimination. While Ainu culture is celebrated in popular Japanese films such as Golden Kamui, people-to-people exchanges, especially with the Maori, remind the Ainu that they are not alone in their campaign for indigenous rights – especially when those efforts are belittled by Japan’s elected representatives.

Late last year, the far-right Liberal Democratic Party [LDP] lawmaker Mio Sugita suggested that people involved in a government project to promote Ainu culture were taking advantage of public subsidies, hinting they were misusing the money.

Sugita, a member of former prime minister Shinzo Abe’s political faction, has a history of making discriminatory remarks against the Ainu. In September last year, the Sapporo Legal Affairs Bureau ruled a 2016 blog post by Sugita about the Ainu people violated their human rights. The Osaka Legal Affairs Bureau issued a similar judgment.

In her post, Sugita derided Ainu and Korean representatives who wore traditional dress at a meeting in Geneva of the U.N. Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination Against Women. She called them “middle-aged women who were completely devoid of dignity”, saying they were engaging in “cosplay” by wearing traditional chimageogori and Ainu dress.

Sugita was widely condemned for her remarks. But the LDP’s vice president, Taro Aso, a former prime minister, finance minister, and arguably the country’s most powerful behind-the-scenes politician, said as recently as 2020 that, for the past 2,000 years, only one race of people – the Wajin – has lived in Japan.

There were no calls for his resignation. Instead, Aso's colleagues pointed out that his remarks contradicted the government’s position that the Ainu are an indigenous people, while apologists dismissed them as “typical Aso” – embarrassing, but essentially harmless. Aso is a far more powerful presence in the LDP than Sugita. He commands fear as well as respect and can get away with saying things that she can’t.

Thankfully, at least in Hokkaido, it is unusual to hear prominent politicians indulging in the kind of bigotry that Aso and Sugita have made their stock in trade. That’s progress of a sort, but it doesn’t mean Hokkaido’s prefectural and local municipal governments are rushing to pass legislation giving the Ainu greater autonomy over their lives.

This is why exchanges with the Maori are seen by Ainu groups as a chance to learn about Maori culture and their political strategy in New Zealand. In addition to the Maori, some Ainu groups have established similar exchanges with indigenous peoples in Canada, the U.S., Australia, Taiwan, Finland, and elsewhere.

It is all well and good that, via popular culture, more Japanese are embracing Ainu culture. Local efforts are being made in many parts of the prefecture to promote the Ainu in ways that would have been unthinkable when I first visited Hokkaido a quarter century ago.

While that might be enough for official Japan, which prefers a cautious approach to Ainu claims to indigenous political, social, and cultural rights as recognized in international law, PR campaigns and pop culture alone are not going to lead to real political change.

The Maori concept of mana motuhake and grassroots exchanges benefit everyone involved. That is particularly true for Hokkaido’s Ainu, who understand that sharing indigenous knowledge is a form of self-determination that will eventually help all indigenous peoples realise their goal of greater political autonomy.

Eric Johnston is the Senior National Correspondent for the Japan Times. Views expressed within are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Japan Times.