Issue:

A gathering of journalists from the Asian region share knowledge and camaraderie in the quest to bring truth to power.

By Daniel Hurst

They say the pen is mightier than the sword. Even so, Zunar, a renowned political cartoonist who has campaigned against corruption in Malaysia, faced an uphill battle with authorities intent on suppressing his freedom of expression.

In recent years, he has been arrested numerous times, detained, charged with sedition and slapped with travel and book bans. His printers were harassed for publishing his work and he was forced to cancel an exhibition because of threats from progovernment mobs. “I told the police: ‘Look, you can ban my book, you can ban my cartoons, but you cannot ban my mind,’” Zunar recalled in the keynote address to a large gathering of investigative journalists in South Korea in early October. “I said to them: ‘I will keep drawing until the last drop of my ink.’”

But Zunar may have the last laugh: the fallen prime minister of Malaysia, Najib Razak, is now the one who is subject to a travel ban and facing a raft of serious charges over corruption allegations that helped fuel his defeat at the general election in May. Najib has pleaded not guilty.

In a passionate speech peppered with light hearted anecdotes, Zunar urged journalists to use their talents to expose wrongdoing and to keep fighting for the truth and free speech, saying it was a never ending marathon. “Responsibility is bigger than fear,” he said. “My philosophy in cartooning is: How can I remain neutral? Even my pen has a stand.”

Zunar was addressing the 3rd Asian Investigative Journalism Conference, held in Seoul’s Millenium Hilton Hotel after previous gatherings in Manila in 2014 and Kathmandu in 2016. The three day event, the biggest one to date, attracted 455 participants and speakers from 48 countries, including investigative and data journalists, media law experts, security specialists and representatives from leading non government organizations. “It’s incredible to see this great ballroom full of investigative journalists from across Asia and around the world,” said Kim Yongjin, editor in chief of the Korea Center for Investigative Journalism, one of the co hosts of the conference.

Apart from arranging panel discussions and workshops, the organizers scheduled extra long coffee and lunch breaks, giving journalists from across the region an opportunity to network and potentially even generate cross border collaborative projects. “We were struck this time by the high levels of collaboration, brainstorming and camaraderie among the participants,” said David Kaplan, executive director of the Global Investigative Journalism Network (GIJN), another co host. “A lot of the action at our conferences takes place not just in the panels and workshops but in the restaurants, bars and hallways.”

Kaplan, a former Tokyo based journalist, said a post event survey of the participants’ reaction was “off the charts” with nearly 98 percent of respondents saying their capacity as journalists had been increased. “It’s also inspiring to our attendees to find out that they are not alone that the threats, harassment, and lack of information access they face are all too common,” he said. “They also discover they share a stubborn commitment to the truth and accountability. That’s a powerful feeling to take home.”

Increasing hostility to ‘fourth estate’

The conference comes amid signs of increasing pressure on journalists in many countries. Apart from the financial difficulties that many legacy media outlets are experiencing as part of the industry’s digital transformation, loud voices can often be heard denouncing reporters. Journalists are also having to confront sophisticated disinformation campaigns along with legal threats and other risks to their personal safety.

Sheila Coronel, an event panelist and dean of academic affairs at the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism, said it was a fraught and difficult time to be an investigative journalist. She said there used to be a broad consensus that the press played an important role as a watchdog on power, as the “fourth estate.” “That consensus is rapidly fraying,” Coronel told the audience, adding that journalists have been denounced in some quarters as “presstitutes,” purveyors of “fake news” or tools of the liberal global elite.

Zaffar Abbas, another panelist and editor of Pakistan’s English language daily Dawn, said journalists are facing multipronged attacks including accusations of being unpatriotic. This notion of patriotism, he continued, was destroying journalism and free thinking.

Maria Ressa, chief executive of the Philippines based social news network Rappler, explained how the outlet has faced numerous threats, including a government attempt to revoke its license. “We feel like the time to fight is now,” she said. “The only way to fight is to shine the light, because if we do not fight we will lose.”

In a later plenary session, Patricia Evangelista, an investigative journalist for Rappler, provided a compelling account of her work in documenting the effects of the so called “drug war” that has led to thousands of deaths at the hands of police or vigilantes.

She emphasized the importance of fact checking in order to make a story bulletproof. “I know the world is howling about fake news but that’s not the worst of it,” she said, arguing it was worse when the general public believed a story about an unjust killing in the drug war was true “but say ‘It’s okay. . . . They deserve it, so what?”

Japanese journalists share their stories

A number of Japanese journalists spoke at the conference about topics ranging from access to information about misuse of taxpayer funds, to shining a light on human rights abuses. Satoshi Kusakabe, a deputy editor of the Mainichi Shimbun, explained how he used Freedom of Information (FOI) laws in 2004 to reveal the lavish spending of then Tokyo governor Shintaro Ishihara, as well as his frequent absences from the office. “It was an eye opening experience for me because [the laws enabled us to act as] a watchdog without any special sources,” he said.

More recently, Kusakabe has used FOI applications to investigate the development of Japan’s controversial state secrets law an extraordinary search that, he said, uncovered 40,000 pages of documents. Kusakabe advised the gathered journalists that even a failure to find specific documents under FOI could become the basis of an article, if it suggested flaws in the proper decision making process.

Makoto Watanabe and Hideaki Kimura, both from the Waseda Chronicle, spoke about their reporting on the practice of forced sterilization in Japan. Journalist and documentary filmmaker Shiori Ito also addressed the conference about her efforts to counter the taboo of sexual abuse in Japan.

Support for jailed reporters

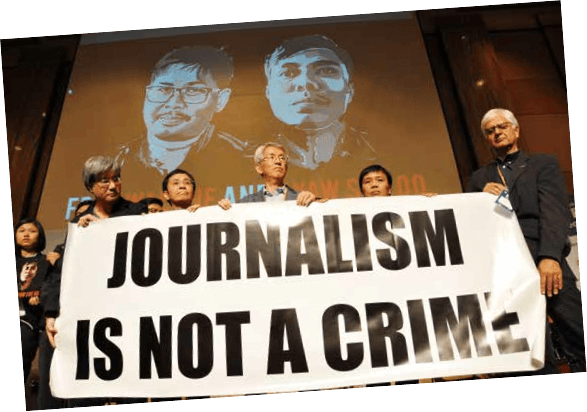

The conference focused heavily on press freedom and at tempts by governments to suppress critical reporting. At the gala dinner on the final evening, the attendees endorsed a statement calling on Myanmar’s government to immediately and unconditionally release Reuters journalists Wa Lone and Kyaw Soe Oo, who were recently sentenced to seven years in prison for breaching state secrets.

The pair, who have maintained they were framed by the authorities, were in the process of exposing a massacre of 10 Rohingya Muslim men and boys in the coastal village of Inn Din in Myanmar’s Rakhine state. They were, according to the conference statement, “unjustly convicted and jailed, simply for their crime of exemplary reporting on a matter of great public interest.”

In a speech to the assembled media, Reg Chua of Reuters spoke of the two journalists’ commitment. “Despite the toll on them personally Wa Lone has a young baby girl he has never met, since she was born while he was in jail they have called at every trial hearing and every opportunity for the need for a free press and the need for independent journalism,” he said. He added that it was important “to call for their freedom and the freedom of journalists everywhere who face a similar plight.”

“It’s a really sad commentary on the world that we live in that we have so many panels here [at this conference] about the harassment, hate and violence directed towards journalists,” said Chua. “Forty two journalists were killed last year, a record 262 were imprisoned this year.”

In the statement, published in seven languages, the conference attendees demanded that governments, multilateral agencies and authorities worldwide “commit to protecting the press, freeing those held arbitrarily, and ending impunity for those who attack journalists.” Attendees held up pictures of the Reuters duo along with a large banner saying “Journalism is not a crime”.

If you can’t beat them . . .

In his speech, Malaysian cartoonist Zunar described finding his way to maintain resolve and a sense of humor throughout his own ordeal. He said that as a cartoonist he believed that “if you cannot beat them, laugh at them.” “No dictator in the world can stand it if you keep laughing at them,” he quipped.

“Just laugh, until one day they introduce an anti laughter law,” he said. “Then if you want to laugh, you’ll need to get a permit, a license from the police, you know, and fill out a form: When do you want to laugh? Next month. Where are you going to laugh? Who are you going to laugh at the opposition or the government? And what kind of laughter will it be hahaha or hehehe? Until then we really have to fight with laughter. It is very, very important for us to use our skills and our own way to fight with corrupt regimes.”

Daniel Hurst is an Australian freelance journalist based in Tokyo who writes news and feature articles for a range of international publications.