The Film Committee’s final screening event of 2020 - our final screening event of the tumultuous 2010s, in fact — returned the audience to perhaps the decade’s biggest story, at least in Japan: the Fukushima disaster.

We had presented the big-budget Fukushima 50 at the beginning of the year, with stars Ken Watanabe and Koichi Sato on hand for the Q&A session. At the end of the year, we were privileged to provide a bookend of sorts with Bolt, the art-film version of similar events, and to welcome veteran director Kaizo Hayashi and star Shiro Sano for an illuminating Q&A.

(In a curious coincidence, Bolt features three of the actors who appear in Fukushima 50, Shiro Sano, Koichi Sato and Kazuhiko Kaneyama, although Bolt was completed several years earlier.)

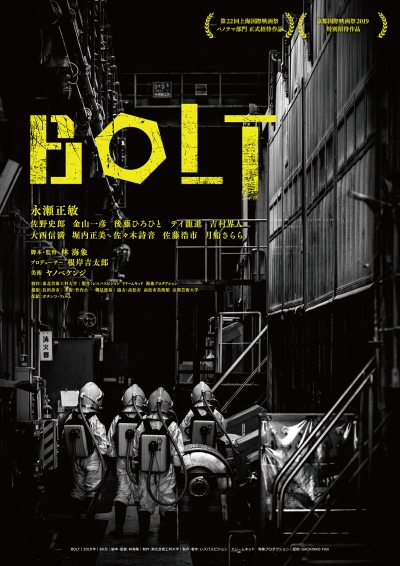

The first responders in Bolt. ©Photo by JUMPEI TAINAKA

The 3/11 tragedy at the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant is never far from the news. Nearly 10 years after the triple meltdowns, there are still 7,000 people at the plant, working on the decommissioning work. In October, the Japanese government announced it would soon decide whether to release a huge quantity of treated water into the ocean so as to speed up the effort; and a November survey revealed that 65% of evacuees say they’re never going back.

While Fukushima 50 pays tribute to the first responders, there were 20,000 people on the site when the disasters hit. Hayashi brought together several celebrated collaborators to create a hauntingly beautiful tribute to one of those 20,000, a nameless character played by Masatoshi Nagase.

©Photo by JUMPEI TAINAKA

In the first of three episodes, which is based on a true story, the nameless man is an emergency worker at the plant on 3/11, leading a small team through a dangerously radioactive environment to fasten a bolt that will prevent contaminated water from leaking. In the second episode, set 2 years later, he is a cleanup technician clearing out houses in the evacuated zone. In the third, set in 2014, he is living and working in a Goodyear Tire garage. On a snowy night, a sports car crashes outside, and he rescues the driver. She bears a striking resemblance to his wife, who was swept away in the 3/11 tsunami…

Arguably the most visually and aurally ravishing work of art related to the Fukushima disasters, Bolt calls to mind the films of David Lynch (Blue Velvet, Lost Highway) and Jean-Pierre Jeunet (City of Lost Children). Rooted in reality but impressionistic in its dreamlike imagery, Bolt evokes the physical, emotional and spiritual tolls of a tragedy that continues to cripple the nation.

©Photo by JUMPEI TAINAKA

Kicking off the Q&A session, film critic Mark Schilling remarked, “Fukushima 50 is somewhat similar in theme to the first part of your film, and I came into this thinking, ‘How can he do this differently?’ That film had a lot of resources that maybe you didn’t. But I saw this and realized that you’re not just talking about Fukushima; you’re talking about something bigger. And to do that, you’ve used genre. The first part is action, the second part is like a docudrama, the third part is sort of noir, but also like Kwaidan, a ghost story. How did you conceive of using those genres to reflect your themes?”

Hayashi replied, “The film is realistic in a sense; it’s [inspired by] what really happened. As is the case with Fukushima 50, we’re dealing with real issues here. But the way I see storytelling is that there’s always a fantasy element in it, there’s always a bigger, broader message when you tell stories. It was my intention to use genre, or various genre tropes, to tell a story that’s bigger than what actually happened. Meaning, that it touches on broader subjects. Meaning, where is mankind headed and how we do make amends with the mistakes that we’ve made?”

Film critic James Hadfield, noting that Bolt has “references to ghosts and hints of the divine,” asked the director about the spirituality in the film. “I felt you were suggesting that maybe through nuclear energy, people had unleashed something that was beyond their understanding. Can you tell us about that?

©FCCJ

Hayashi responded immediately and tellingly, in English: “Yes. I agree with you. It’s very dangerous. We’ve touched Pandora’s box already. Many countries are the same, but Japan is the most dangerous. Other countries have now stopped the operation of nuclear plants. In Japan, with Fukushima, the box is opened. We can never close it. Why does someone want to open it again? It’s too dangerous. That’s my message to humans.”

Mentioning that two reactors have recently restarted in Japan, one audience member asked the director whether he thought art and cinema could effect change. Said Hayashi, “One of the characters in Bolt is asked what he’s planning to do, going forward, and he answers, ‘I have no other choice but to continue, to live.’ As a filmmaker, I think that’s our plight. To live, for creators and artists, is to continue making art. That’s the only way that we can arrive at ‘the light.’ I don’t look at it as resistance, but rather, the only way to go forward.”

Bolt had a rather unique production history. Asked to clarify the process, Hayashi explained, “The first episode I shot was the last episode you saw, Good Year. The idea was to release it as a short film. I didn’t have any plans to shoot other episodes. I shot the second chapter, Life, (two years) later, and went to the 20km evacuation zone three times in order to do that. Then I realized that I should shoot the first episode you saw, Bolt.

©Koichi Mori

“I was talking to (artist) Kenji Yanobe, who became the production designer for the film, and we decided to shoot it on a set that he was creating inside the Takamatsu Art Museum (in Kyushu). I knew, of course, that we were going to have to spend a lot of money on that episode because of the set design. So Mr. Yanobe said that he would shoulder the costs if we made it as part of his exhibition at the Takamatsu museum.”

In a first for Japan, the episode was shot during regular museum hours, and the exhibition was the museum’s main attraction. Surely that presented enormous challenges for Hayashi and his team?

“We had visitors and patrons of the museum coming to watch while we were shooting,” the director said. “We didn’t want to bore them between takes, while we were doing the setups, so I would go out and explain to them what the next scene was about.

©Photo by JUMPEI TAINAKA

“When we shot the scene in the tunnel, the actors were inside the set. In order to show the visitors what was happening in there, we had a camera inside and connected a monitor to it so they could watch. We also prepared a little director’s chair in front of the set, and there was a kid who came every day and sat in that chair, watching our progress.” He laughed, “I’m sure he’s a director by now.”

Shiro Sano is a veteran stage actor, as well as one of Japan’s most prolific performers on screens large and small. Still, performing in the museum — in full Hazmat suits and helmets — must have been a little strange, no?

“It was a lot of fun to do, actually,” he said. “My first film with Mr. Hayashi, and my first leading role, was in To Sleep So As to Dream. The architecture, the buildings that were shown in the film, were a very important element of the visuals. I think you can say that they were almost characters themselves. The same was true with the art direction and production design on Bolt. They were as important a force as the actors. Shooting in the museum, with the set already there, made me very aware of the fact that as an actor, I’m only on a par with the design.

Masatoshi Nagase works on a gyroscope, one of Hayashi's favorite motifs. ©Photo by JUMPEI TAINAKA

“I’ve made some 10 films with Mr. Hayashi, and this one was the closest to the experience I had shooting To Sleep So As to Dream. I say that because first, we had the same cinematographer, Yuichi Nagata, who always works with Mr. Hayashi. Added to that was the fact that there wasn’t a lot of dialog, which was very much like the experience of To Sleep So As to Dream, which is almost entirely a silent film, although the stories are different.”

Bolt’s production was also unique for another reason, as an academic in FCCJ’s audience pointed out. She asked about the schools that were listed in the credits. “We used professional actors, and the production designer, DP and sound department were all professionals, as well as myself,” explained Hayashi. “But we had about 25 students from the Tohoku University of Art and Design (where Hayashi is a professor), six graduate students from the Kyoto University of Art and Design and about 10 more students who were studying under Mr. Yanobe.

“We had each of them perform one task, after we gave them some quick training. We didn’t ask them to be assistants, but rather, to be completely responsible for their tasks. I discovered they were quite capable. I’d done the same thing with my previous film, Miroku, and it had gone quite well."

©Koichi Mori

Sano interjected, “There were also a few university students acting, but it was a thoroughly professional atmosphere on the set.”

Hayashi continued, “I think that films should be made by the younger generation. Of course Japanese film has a 120-year history, but when we go way back, we have filmmakers like Masahiro Makino, who was making films at the ripe old age of 16. It’s only appropriate that we have young people make films. On my films, I want to utilize their strength and just be an old man on the set.”

Sano, who’s well known as a connoisseur of ghost stories (he has appeared around the world in staged readings of Lafcadio Hearn works for the past decade), was asked whether Bolt might inspire him to create a new, Fukushima-themed tale. “I don’t have any plans, but I’m open to offers,” he said, looking pleased at the thought. “Through my readings of Lafcadio Hearn, I know that he also had experience with natural disasters, including the Ansei Great Earthquake, which led to the (1855) Tohoku tsunami.

©Photo by JUMPEI TAINAKA

“Right after 3/11, I started to perform Hearn’s A Living God (in which the term tsunami was used for the first time, in 1897). What he depicts in that story is not related to Fukushima, of course, but it teaches us a lot about natural disasters, about the decisions we make in the face of these disasters and how we live, going forward. I wouldn’t equate Hearn’s natural disasters with Fukushima, which was partially a manmade disaster, but I think there’s a lot of wisdom in terms of how to react to such situations.”

Loath to see such an enlightening Q&A session end on such a somber note, a Japanese film critic asked what many others surely had on their minds: “Seeing you two together on stage, I wonder if we can expect a new detective story soon?”

©Koichi Mori

The reference was to Hayashi’s 1986 directorial debut, To Sleep So As to Dream, made when he was just 29. Championed by the late, great film historian (and FCCJ mainstay) Donald Richie, who had done the subtitles, the film had earned Hayashi international acclaim, domestic awards and enduring cult status. It had also launched his long collaboration with Sano, whose role in the film as an egg-addicted, brain-addled detective, is thoroughly unforgettable.

The men smiled and nodded, nearly in unison. Said Hayashi, “The character of Detective Jin Uotsuka is really interesting. At one point I was considering making To Sleep So As to Dream into a series.”

Said Sano, although it’s unclear whether he was being serious, “After seeing the digitally remastered version*, I now really want to play the part of the butler, who’s an old man (in the original, he was played by 75-year-old Yoshio Yoshida). It doesn’t have to be a recreation, but if we could do a remake with [everyone aged], that would be interesting.”

With the poster for Bolt. ©FCCJ

Kaizo Hayashi nodded once again. “Let us think about it.”

*For those lucky enough to be in Japan, the digitally remastered To Sleep So As to Dream will be playing in theaters alongside Bolt. For those overseas, urge your local festivals to program both.

© L'espace Vision, Dream kid, Kaizo production