Issue:

August 2023

Journalists in the U.K., Japan, Palestinian territories and China honored at FCCJ Freedom of the Press awards ceremony

The FCCJ honored its 2023 Freedom of the Press winners in a hybrid ceremony last month, with participants accepting the awards in person and online in locations as diverse as the U.K., Okinawa, China, and Palestine.

“Since FCCJ’s founding in 1945, freedom of speech has been at the heart of what the club stands for. Back then, foreign correspondents had to navigate U.S. General Douglas MacArthur and the post-war Japanese government in order to write about the what was happening with the Occupation,” outgoing FCCJ president (now ex-officio) Peter Elstrom said in his opening remarks.

“Now, if anything, freedom of the press is under assault as never before. Not only in autocracies like China and Russia but also in democracies, including India, the United States and Japan.”

Elstrom noted specific cases in which journalists in Bangladesh, the Philippines, Russia, and China had been killed, jailed, threatened, or harassed, intimated and expelled for “simply doing their jobs”.

Journalists in Japan are relatively free, he added. But the media is often contained through intense cultural pressures and libel laws that are very favorable to the plaintiffs. “That’s led to a Japanese press that is, at times, complicit in the face of wrongdoing and silent in exposing bad actors,” Elstrom said.

The Freedom of Press committee chooses awards winners for two categories - Asia and Japan - with nominees including individual journalists and media organizations that have distinguished themselves in the struggle for press freedom over the previous year. There was also a Lifetime Achievement Award.

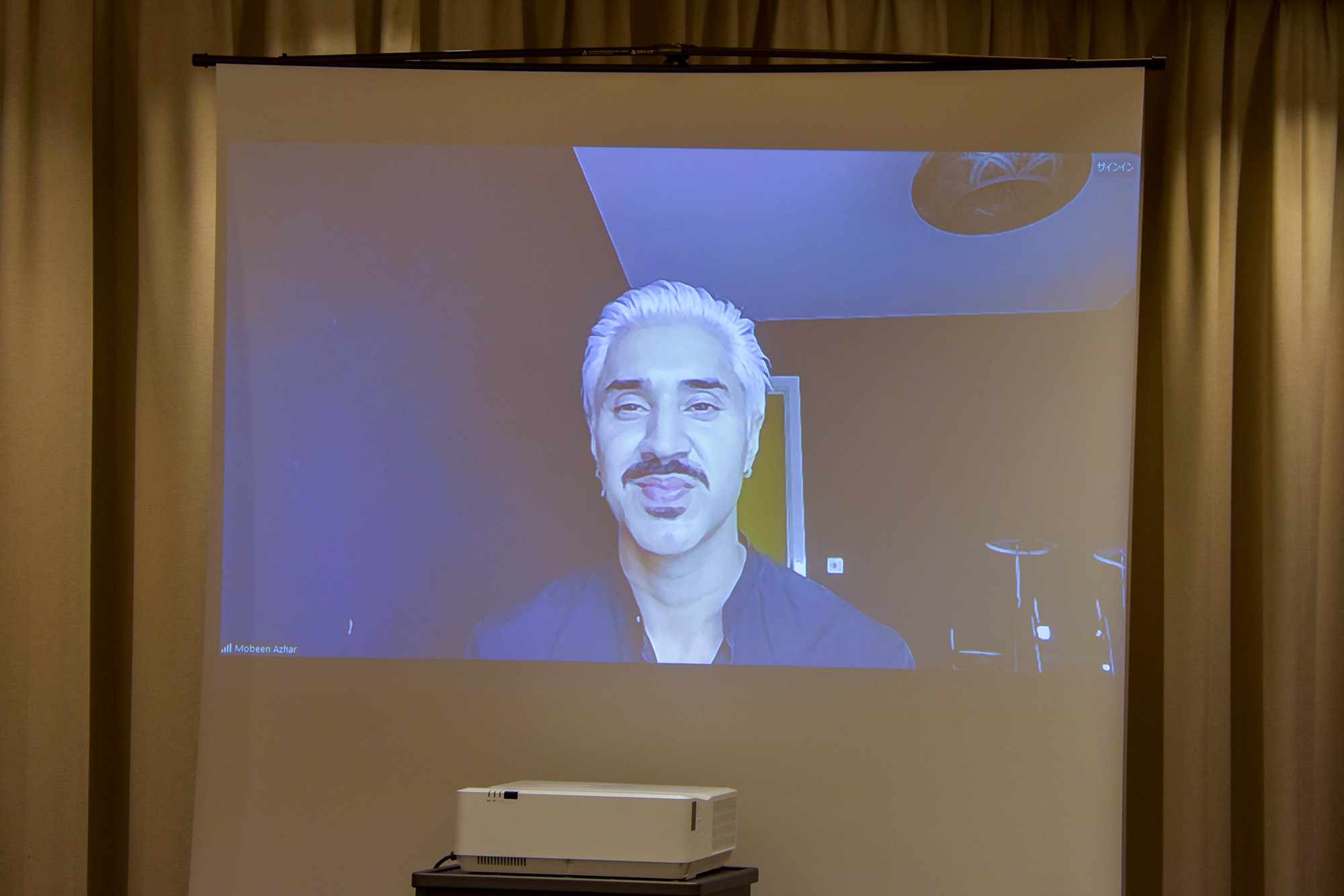

The winners of the Freedom of the Press Japan award were Megumi Inman and Mobeen Azhar, who produced a BBC documentary, Predator: The Secret Scandal of J-Pop, about sexual abuse allegations involving the talent manager Johnny Kitagawa. The film pushed the long history of Kitagawa’s abuse of children back into the headlines and forced the Japanese media to reflect on their own negligence in covering the story because of their connections to Kitagawa’s influential agency, Johnny & Associates.

Following March events at the FCCJ to discuss the film, the club hosted press conferences by Kauan Okamoto and Yasushi Hashida – who alleged they had been abused by Kitagawa – that were well attended by the Japanese media.

“As journalists who are not resident in Japan, we were aware of accusations of parachute journalism,” Inman said. “But we’ve been humbled by the response we’ve received in Japan to the film. Much of the Japanese press had failed to cover the story of Kitagawa’s abuses. But the film’s release started a national discussion about it.”

The awards ceremony came just before a visit to Japan by the Office of the U.N. High Commissioner for Human Rights’ working group on business and human rights in late July and early August to meet with former members of Johnny & Associates. Their report will be submitted to OHCHR next June.

National discussion and international attention on Kitagawa were only possible because of the bravery and testimony of the abuse survivors, Azhar said.

“To all who spoke to us, who continue to speak out, and to those survivors of abuse thinking about speaking out, we express our absolute solidarity and respect,” he said. “Japan and much of the world is listening to you. So please continue to speak out.”

One of the few Japanese publications to pursue the abuse scandal was the weekly magazine Shukan Bunshun. In 2001, Bunshun, alone among major media outlets, ran a series of reports alleging sexual abuse by Kitagawa.

Kitagawa sued Bunshun for libel and was awarded damages, but the judgment was partially overturned on appeal, with the Tokyo high court ruling in 2004 that the magazine had sufficient reason to publish the allegations against him. Kitagawa’s appeal was rejected by the supreme court. He was never charged with a crime.

Now, more than 20 years later, Shukan Bunshun stands entirely vindicated.

Daisuke Takahashi, a journalist at the magazine, blamed decades of silence by Japan’s mainstream media for effectively allowing the abuse to continue.

“When we at Shukan Bunshun asked the victims why they had not spoken up about being harassed, they said they had actually spoken to the media in the past about sexual harassment at the Johnny’s office,” Takahashi said. “But their stories were not picked up by the Japanese media. They thought the stories had been spiked and that they had been ignored. That’s why they could not speak up.”

Decades of media silence about abuse by an organization close to powerful public figures, including politicians, was mirrored in the case of the Unification Church, officially known as the Family Federation for World Peace and Unification. But the code of silence ended in July 2022 with the assassination of former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe.

After the alleged killer, Tetsuya Yamagami, told police he had shot Abe because he was angry about the politician’s ties to the church - which he blamed for destroying his family - a series of almost daily mainstream media reports revealed the extent to which Abe and senior Liberal Democratic Party leaders had sought the church’s cooperation and assistance.

For analysis and comment, many turned to freelance journalist Eito Suzuki who – almost alone among Japanese journalists - spent years investigating the church. For much of the latter half of 2022, Suzuki appeared on mainstream TV programs and in newspaper reports on an almost daily basis to detail the depth of LDP-church ties. Suzuki received an Honorable Mention for his work.

“The Japanese media did not monitor the relationship between the church and the politicians. It was only with Abe’s shooting that they finally began disclosing these connections,” he said.

Suzuki praised an October 2022 FCCJ press conference featuring Sayuri Ogawa, a second-generation church follower who broke with her parents over their involvement in the organization. In a moment of drama, her press conference was interrupted by a messaged faxed to FCCJ by her parents labelling her a liar and urging her to stop speaking The press conference continued.

In echoes of the Kitagawa scandal, Suzuki said other victims of the church needed support. “These are people who are suffering from defamation and harsh slander (by the church),” he said. “Our mission should be to figure out how to protect them.”

The Freedom of the Press Asia award went to the late Palestinian journalist Shireen Abu Akleh of Al Jazeera, who was killed by what appeared to be sniper fire on May 11, 2022. She was shot while covering clashes between the Israeli army and protestors in the West Bank city of Jenin. Al Jazeera said she was wearing a helmet and vest clearly marked “Press” when she was shot “in cold blood”.

The Israel military said it returned fire after coming under attack and suggested that Abu Akleh was killed in crossfire, but it was noted that Israeli forces have been accused of targeting journalists in the past.

“Shireen was a household name everywhere in the Palestine territories and the Arab world. Everyone knew her,” said Walid Al-Omari, Al Jazeera's Palestine bureau chief, in accepting the award.

Al-Jazeera has demanded an investigation into Abu Akleh's death by the International Criminal Court.

“With the FoP award and other actions, I hope we can do something more for colleagues all over the world who sacrifice their lives,” Al-Omari said.

The Honorable Mention Asia award went to the FCCJ’s sister organization in China, the Foreign Correspondents’ Club of China. In a 2022 report, the FCCC, which does not release the names of its members or hold public events, detailed a litany of abuses against foreign journalists and their local staff by Chinese authorities, showing just how daunting a challenge it is to cover the country.

Some FCCC members joined the awards ceremony remotely from China, while Koichi Yonemura, a Japanese journalist from the Mainichi Shimbun who was an FCCC member until returning to Tokyo earlier this year, accepted the award on their behalf.

“It’s a really sensitive time now, and we can’t reveal the names of current FCCC board members or their affiliations,” Yonemura said.

The Lifetime Achievement Award went to broadcast journalist veteran Hisayo Saika, who is known for her film about attempts by the Japanese right to politicize high school education.

Saika has had a long career in TV journalism, mostly with Mainichi Broadcasting System. She first became a news reporter in 1989, covering education, and since 2015 has been working as a documentary director. She won the Broadcast Woman Award in 2018.

Speaking from Okinawa, Saika said she would continue to monitor political intervention in Japanese education. “I am really worried that political intervention will change the shape of this country,” she said.

Eric Johnston is the Senior National Correspondent for the Japan Times. Views expressed within are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Japan Times.