Issue:

August 2023

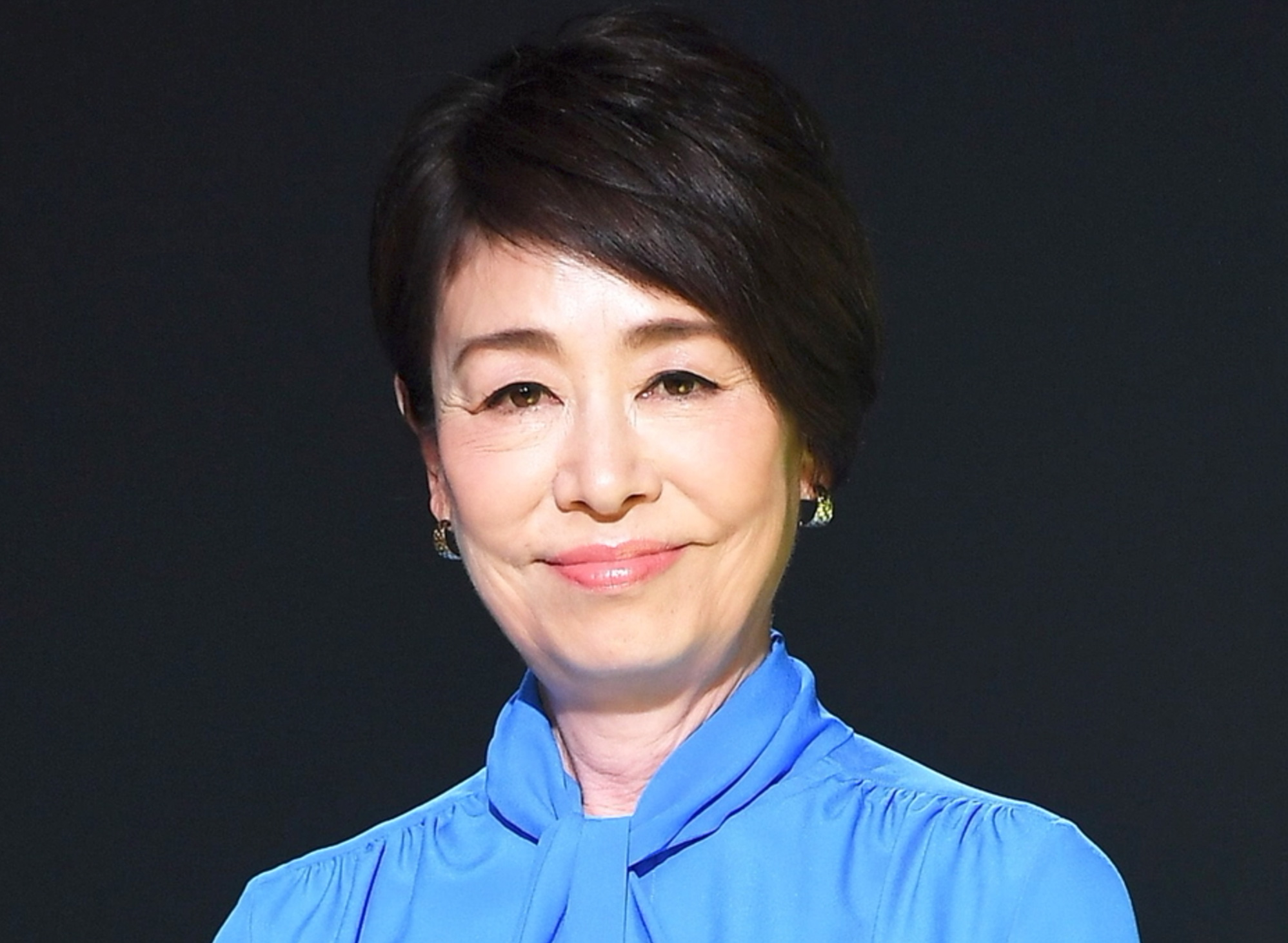

TV anchor Yuko Ando on how she went from ‘plastic chrysanthemum’ to primetime legend

One of the best-known faces in Japan, Yuko Ando has for years been a staple of primetime TV news shows. In an industry where women have often been relegated to decorative sidekicks to their male colleagues, Ando stands out for being not just the main anchor on shows such as FNN Super Time, News Japan and Super News, but as a journalist with her own unassailable resume.

In addition to interviewing many of the world’s most famous political figures, including U.S. President Bill Clinton and British Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, she has worked in numerous conflict zones. Among the stories she recalled during an open lecture on July 5 at the University of the Sacred Heart in Tokyo was how she nearly died when a landmine exploded near her during a reporting trip to Cambodia.

Like all great careers, Ando’s owes something to serendipity. She was recruited as an assistant by TV Asahi 40 years ago, luring her away from a potential job in hotel management. “I never imagined I'd become a journalist,” she told a packed audience. “I studied the hotel industry at an American university and was saving money to go to the United States.”

One of the attractions of her new post was financial: ¥5,000 a day was a lot of money in the early 1980s, she said. She quickly found, however, that her job was simply to nod alongside an older male presenter. Ando colorfully described her role as being a “plastic chrysanthemum flower”. “This was my first foray into the world of news reporting,” she said.

Her first big interview was with Shin Kanemaru, then secretary general of the Liberal Democratic Party, later a figure of infamy when police discovered gold bars under his bed, along with over $50 million in bearer bonds. Ando says she was chosen by her boss because he thought she might disarm the television-phobic Kanemaru. “Such a person has to be a young girl, he reasoned.”

The LDP grandee appeared in shorts and an undershirt, recalled Ando, and told her to go home. She battled though Kanemaru’s sullenness, managing to bag the names of several new appointees in a cabinet reshuffle. “I was happy that I was able to film the interview, but the program producer told me I did it because I was a young girl. I was very disappointed, but on the other hand, it was true.”

Later, when she reflected on the encounter, she concluded that if the “young girl” tag could be made to work for her, she could exceed expectations and render the tag meaningless. “From that point on, I was committed to ‘working like a dog and acting like a lady,’ so to speak.”

Ando said her philosophy on life as a woman in a mostly male industry was reinforced during a trip to South Africa in 1993, after the fall of apartheid and the release of Nelson Mandela. Japanese were considered honorary whites at the time, she said. “The locals sarcastically referred to the Japanese as bananas that were yellow on the outside but white on the inside.”

She said she met a seven-year-old black girl and asked the obvious question: Did she regard their different skin colors as a problem? “She replied: ‘The difference in skin color is just a difference, not a problem.’ I used to think that physical differences were my problem, my handicap. But then I realized that it is our mind that makes the existence of difference a problem.”

Ando said she became freer by shutting off the part of her mind that says, “because I’m a woman”.

Nevertheless, little changed for women in Japan during the decades she was reporting. A key factor, she said, is the LDP-dominated political system, which has in effect relegated women to appendage roles as assistants, housewives and mothers. “All rules have been made mainly by men. However, men do not think it is their problem.”

Structural sexism is the subject of Ando’s doctoral thesis (国会における女性過少代表の分析—自民党の政治指向と女性認識の形) completed (for Sophia University) and published last year as a book. “The book takes as its starting point the question of why there are not more female members of national legislatures.” The conclusion, she says, is that it is society's “perception" of women”.

That, she admitted is vague. So, she set out to analyze how those perceptions of women have been formed, focusing on the LDP, which has shaped Japan's political culture as the party that has been in power almost uninterrupted since the end of World War II. “What emerges is that the LDP has formed and reproduced the ‘perception of women’ as a party strategy to this day,” she said.

It's a weighty topic, and one that must surely have Kanemaru’s successors squirming in their seats, but Ando says the LDP has invited her to speak about the book – political flexibility, of course, is one reason why they have survived all these years.

As for advice to the mainly female audience at Sacred Heart, she told them to resist the urge to conform. “There is pressure for homogeneity and intolerance of those who stand out. We may not want to make the situation more troublesome, but we can change it by raising our voices when something is wrong.”

Nao Kato is a PhD student at University of the Sacred Heart, Tokyo. David McNeill is professor of communications and English at University of the Sacred Heart in Tokyo, and co-chair of the FCCJ’s Professional Activities Committee. He was previously a correspondent for the Independent, the Economist and the Chronicle of Higher Education.