Issue:

February 2024 | Cover Story

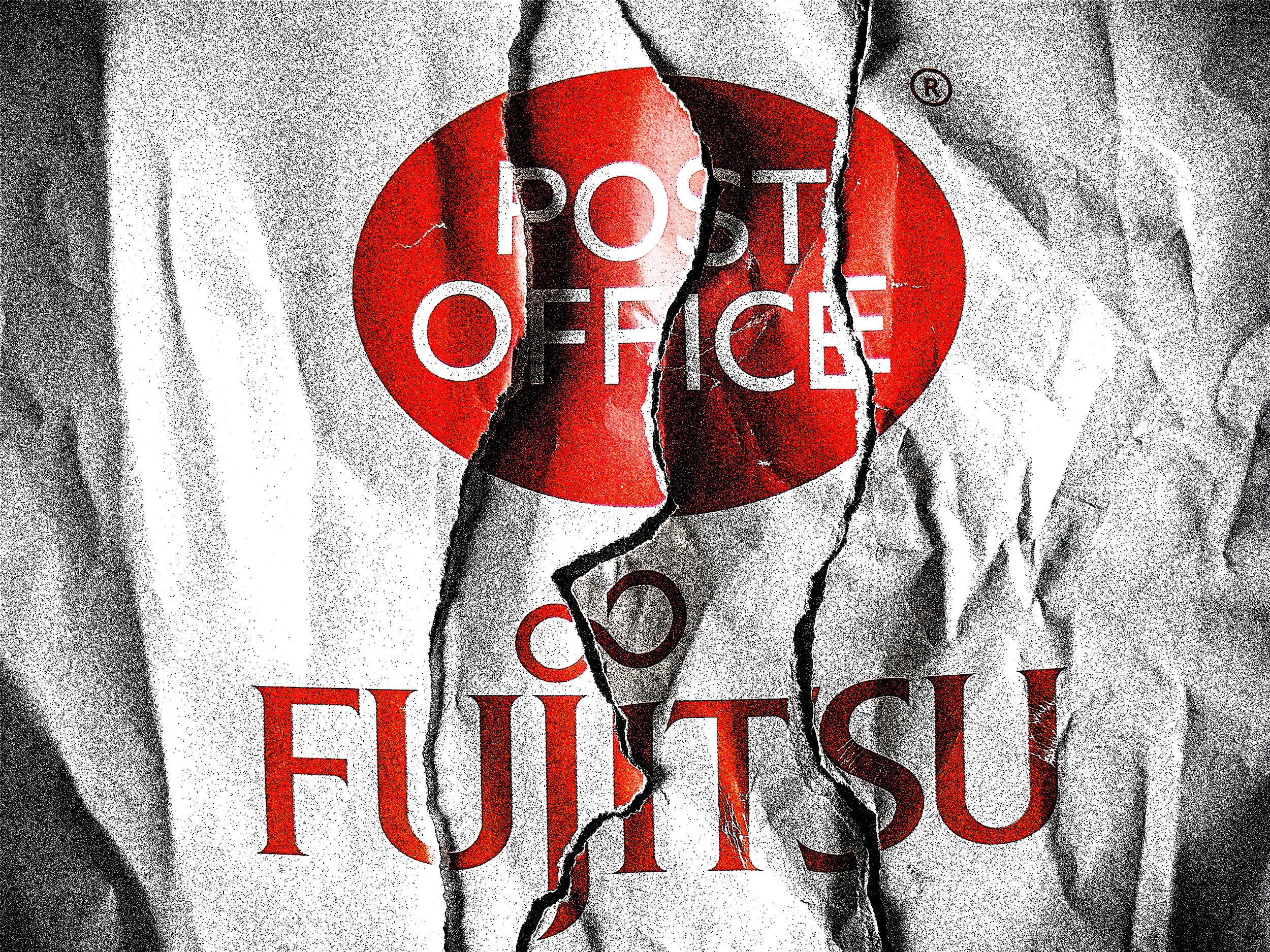

The Japanese tech giant Fujitsu played a key role in the Great British Post Office scandal. Now it faces a day of reckoning.

“Rebuilding trust” was the theme of this year’s World Economic Forum [WEF] at Davos. Few among the 3,000 or so of the globe’s wealthiest and most powerful who flew in by private jet and helicopter probably knew what it meant, but that’s hardly the point of the Swiss schmoozefest held every January. Underneath an Alpine avalanche of virtue-signalling and edifying speeches – redemptive excuse for parties, luxury and other assorted hedonism - lies the hard business of networking and cutting deals.

Fujitsu spared no expense on making a splash at Davos. Seven top executives, including CEO Takahito Tokita, were on hand. On the main promenade leading to the WEF conference center, protected by rooftop snipers and roadblocks, the Japanese computer giant turned an upmarket bakery, patisserie and confectionery shop into the “Fujitsu Uvance House.” Cash registers and refrigerated counters were replaced with sofas, bonsai trees, orchids and a well-stocked cocktail bar. Visitors were invited to “learn more about how the planet, prosperity, and people framework is already making inroads to a better tomorrow”. (A sample insight: “Happier employees can have a positive impact on your value chain.”) Guest speakers included the “chief futurist” of a German software company, and a 2thought leader” from the Financial Times. If all this sounded too exhausting, you could brush up on calligraphy or experience the tea ceremony, all at maison Fujitsu.

Alas for Tokita, it was not to discuss how Fujitsu could sprinkle stardust that a BBC television crew collared him outside on the promenade. Would he like to apologize? “Yes, yes, of course,” Tokita replied in halting English. “Fujitsu has apologized for the devastating impact on them, their lives and their families.”

Tokita’s belated apology was for Fujitsu’s role in blighting the lives of hundreds of British sub-postmasters wrongly convicted as a result of the firm's faulty Horizon IT system.

In 1990, Fujitsu acquired 80% of International Computers Ltd. [ICL], a one-time UK “national champion” that gave Fujitsu access to important and lucrative UK public-sector contracts. In 1998, ICL became a fully owned subsidiary of Fujitsu, and in the following year, the UK Post Office installed Fujitsu’s Horizon accounting system in its nearly 20,000 branches.

What Fujitsu called the “largest non-military IT system in Europe” was riddled with bugs that led to false reporting of large cash shortfalls in post office balances. The Post Office ignored mounting evidence of IT errors, and between 2000 and 2015, prosecuted 844 sub-postmasters – an average of nearly one a week.

A total of 705 people were imprisoned following convictions for false accounting, theft, and fraud. Some were financially ruined and ostracised by the communities where they lived and worked. Four committed suicide. Another 33 died before seeing justice.

Seema Misra served four months of a 15-month jail sentence in 2011 while pregnant. An audit had found a discrepancy of £74,000 [¥13.8 million] in the accounts at her post office. After release, “People stopped talking to us,” she said. “I was beaten up and called a ‘f***ing P*ki, coming to this country and stealing old people’s money.”

She developed depression and felt too ashamed to show up at her children’s school. Her criminal conviction made it difficult to find new work.

Martin Griffiths was suspended after auditors found a £23,000 hole in the balance at his post office. He was reinstated, but losses continued to escalate. More than £57,000 was “missing” from January 2012 to October 2013, and to make up the shortfall, his parents had to lend him their life savings. There was also an armed robbery, and a large sum of cash was taken. The Post Office cancelled his contract. Soon after, he took his own life.

Nicki Arch was tried for fraud, theft, and false accounting, but was acquitted by a jury. The ordeal led to a nervous breakdown, for which she was hospitalised. According to Private Eye magazine, she was “penniless for years and spent a decade on antidepressants.” Her marriage was also ruined.

Phil and Fiona Cowan faced similar accusations of money missing from their post office. Fiona was charged with false accounting and was “spat at in the street and called a thief”. In 2009, she committed suicide, aged 47. In December 2019, the Post Office agreed to a £58 million settlement of civil cases with 555 claimants. Some £46 million was immediately swallowed up by victims’ legal fees.

In a ruling on the Horizon system, Mr. Justice Fraser said that “assertions and denials” by the Post Office “ignore what has actually occurred,” and were “the 21st century equivalent of maintaining that the earth is flat”. He was scathing of a Post Office description of Fujitsu as “an organisation which was thorough, professional and conscientious and which took considerable care to ensure that matters were properly investigated and dealt with”.

Judge Fraser said: “I do not see how a thorough, professional and conscientious organisation can have produced for disclosure in this litigation so many thousands of KELs [known error logs] during 2019 itself, both during and even after the trial. I reject that description; it is an inaccurate description of Fujitsu and/or its investigative motivation.” A technical annex to his ruling lists 29 different “bugs, errors and defects” present in Horizon.

Computer Weekly cited a former senior developer at Fujitsu UK as saying that Horizon’s problems were well-known within Fujitsu even before the launch, and that its electronic point-of-sale system was built with “no design documents, no test documents, no peer reviews, no code reviews, no coding standards”.

In April 2021, the UK Court of Appeal quashed the convictions of 39 former sub-postmasters, declaring them “an affront to the public conscience”. This opened the way for legal action over malicious prosecution, with potential for significant damages.

The UK government agreed to a judge-led inquiry into the scandal, with statutory power to compel witnesses to give evidence and hand over documents.

The public inquiry has produced mountains of often highly detailed and complex testimony. Meanwhile, the wheels of British justice have been grinding at a stately pace and immoderate cost. (The most sought-after English barristers, who represent cases in court, can charge between £500 and £600 per hour.) By December, only 93 of the wrongful convictions had been overturned.

Karl Flinders, who had first reported the scandal for Computer Weekly, showed dogged persistence and determination in pursuing his investigation, as did freelancer Nick Wallis, who reported for Private Eye and presented an 11-part series for BBC radio called The Great Post Office Trial, as well as a BBC television documentary, Scandal at the Post Office. The rest of the British media took a desultory interest, with only occasional reports or features. No leading newspaper seized the chance to launch a sustained, old-fashioned crusade to demand redress for the innocent and punishment of the guilty. In Japan, the Post Office-Fujitsu scandal remained almost unknown, despite all the major Japanese media organisations maintaining large London bureaux.

In the end, it took a four-part TV docudrama, screened on successive January evenings by the ITV channel, to fully ignite public anger at what had happened. Mr Bates vs the Post Officetook its name from Alan Bates, one of the wronged sub-postmasters and a campaigner for justice. Even the writer and producer were taken aback by the way the drama electrified the nation’s conscience. Prime Minister Rishi Sunak announced emergency legislation to exonerate all those who had been convicted. Jolted from their torpor, media and politicians have competed to wax indignant, and a furious search is underway to uncover the full facts, and above all, to apportion blame.

Rather than duck, dive and squirm, Fujitsu decided the best course of action was honesty. Fujitsu Europe director Paul Patterson apologised to the inquiry for an “appalling miscarriage of justice” and called the deliberate omission of Horizon error logs from witness statements presented in court “shameful and appalling”. He said Fujitsu had “let society down” and would contribute to a fund for “victims of this crime”. The government minister in charge of the Post Office has said the compensation bill is likely to cost £1 billion – “maybe more than that” – and Fujitsu is expected to fund “hundreds of millions".

Fujitsu will not bid for any more government contracts until the public inquiry is complete. In spite of being mired in controversy, since 2012 Fujitsu has been awarded almost 200 contracts in the UK public sector, worth a total of about £6.8 billion. About 43 of these contracts, worth about £3.6 billion, are still in operation, including for the Foreign Office and the Ministry of Defence.

Few British politicians emerge well from the scandal.

The Labour government of Tony Blair took office in 1997, one year before ICL was absorbed by Fujitsu. An adviser warned Blair that Horizon was “plagued with problems”, and a Treasury document of 22 April 1999 stated that “independent reviews of the Horizon project by external IT experts have all concluded (most recently this week) that ICL Pathway [the subsidiary building system] have failed and are failing to meet good industry practice in taking this project forward, both in their software development work and in their management of the process”.

Sir David Wright, the then British ambassador to Japan, countered that scrapping the system would lead to the collapse of ICL and have “profound implications … for bilateral ties” with Japan. Blair decided it should go ahead.

From 2010 to 2015, the Conservatives ruled in coalition with the Liberal Democrats. Ed Davey, now LibDem leader, was in charge of the Post Office from 2010 to 2012. In spite of claiming that he was lied to “on an industrial scale” by the Post Office, Davey has refused to meet with Bates or issue an apology. His popularity has plummeted.

The BBC has obtained unredacted minutes of an April 2014 meeting of a Post Office sub-committee called Project Sparrow that secretly decided to sack forensic accountants who had found bugs in the Horizon system. A senior civil servant from the UK government – the 100% shareholder of the Post Office – belonged to Project Sparrow and therefore agreed to the coverup.

The latest Post Office accounts show that between 2014 and 2023, Post Office CEOs were paid an average annual bonus of £287,900 on top of an average £319,100 in basic pay. No Post Office or Fujitsu executive in office during the scandal has been arrested. Indeed, many have gone on to hold other lucrative positions in the UK.

It has taken two decades since Alan Bates first began campaigning for the government to promise swift redress to the sub-postmasters. Victims of the UK’s contaminated blood scandal have been waiting even longer for justice.

In the 1970s and 1980s, 4,689 people in the UK with haemophilia and other bleeding disorders were infected with HIV and hepatitis through contaminated transfusions. Since then, more than 3,000 have died, and of the 1,243 infected with HIV, fewer than 250 are still alive. Private Eye published its first report on the scandal back in 1987.

The Infected Blood Inquiry heard evidence between 2018 and 2023 while victims continued to die. The report will finally be published on 20 May. To date, the inquiry has cost the UK taxpayer £130,350,00, including £6,317,028 for the hire of barristers and another £25,702,353 on miscellaneous legal costs. Travel and subsistence consumed another £1,459,500. Experts were paid £533,462.

Surviving victims and bereaved partners have received interim payments of £100,000 but the UK government has to decide on final pay-outs.

Like many other advanced countries, Japan settled its own blood product scandal decades ago.

Peter McGill is a UK-based writer. A former Tokyo correspondent of the Observer, he was FCCJ president from 1990 to 1991.