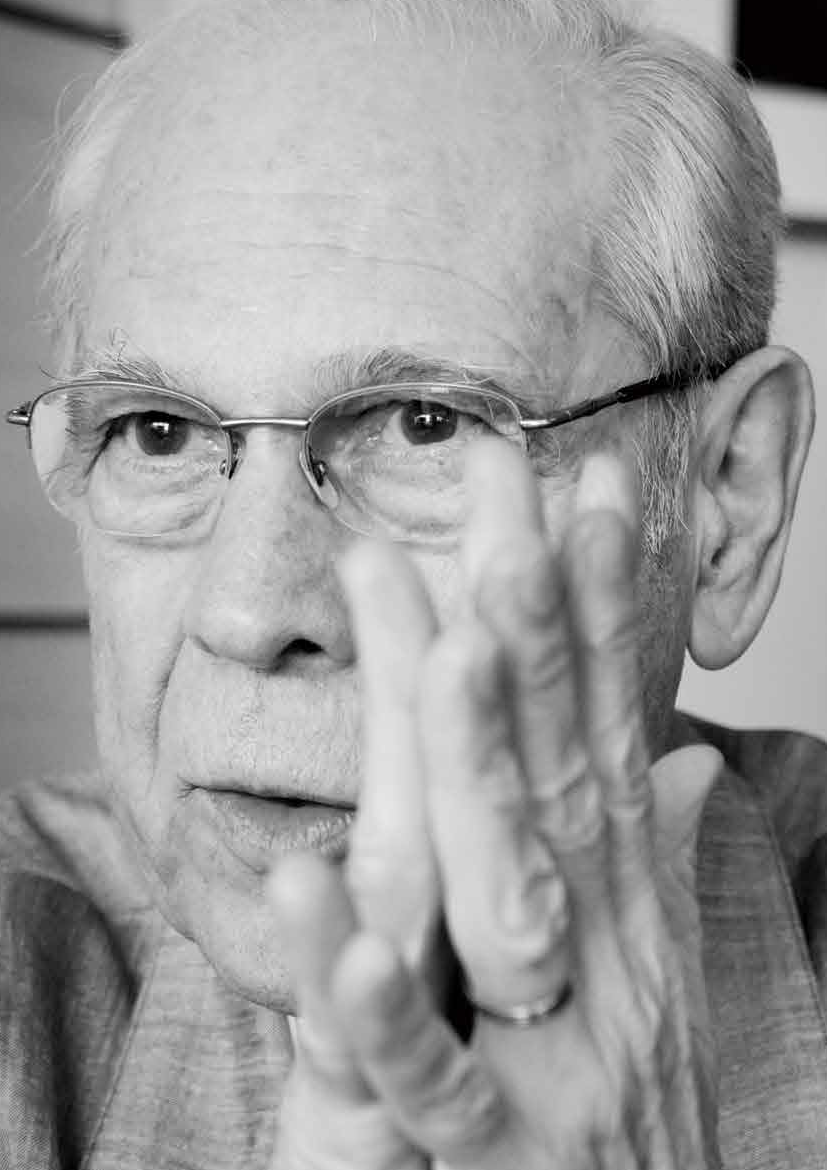

Issue:

For a 17 year old who had been through a Depressionera childhood, punctuated by frequent moving around and the eventual break-up of his family, the U.S. Navy seemed like a ticket to another world for the young Charles A. Pomeroy. Partly inspired by tales of exotic places in the war time adventures of his new stepfather, whom he convinced to adopt him so that he could sign the papers allowing Pomeroy to enlist, military service did indeed turn out to be his pass port to a different world.

“That was the smartest move I ever made in my life,” is how Pomeroy describes the decision he took back in 1947.

Only a few years later, while still a teenager, Pomeroy found himself part of one of the first naval aviation squadrons deployed in the Battle of Pusan Perimeter.

“I was by the pool in Hawaii on June 25, 1950, after being given the day off after a night-training flight, when I heard the [Korean] war had started,” recalls Pomeroy, whose squadron was then sent to Guam’s Andersen Air Force Base for deployment. “We knew something was up when we landed and were greeted by a pickup truck from which flight crews were served cold beer. That was most unusual in a Navy setting.”

Pomeroy’s squadron was soon sent into action, given orders to “stop anything that was coming south,” referring to the North Korean and Chinese forces that were then in control of most of the peninsula. The military command, however, was worried about the danger of the cutting-edge technology in their Lockheed P2V Neptune planes falling into communist hands one had been shot down and they were subsequently restricted to reconnaissance missions. Nevertheless, among the 79 missions that Pomeroy flew during the conflict were a number when his plane came under fire, including an encounter with a North Korean anti-aircraft ambush that downed his wingman.

The wingman’s crew ditched their plane off the coast and escaped into their life rafts. Pomeroy’s crew held off the enemy patrol boats intent on capturing the airmen, until the arrival of a British light cruiser, the HMS Kenya. Short of fuel, they headed back for Japan and landed at Iwakuni, an airbase in Yamaguchi Prefecture.

“We jettisoned everything we could,” Pomeroy remembers. “We came straight in and landed, and once we pulled off the runway, the starboard engine cut. We taxied in on the port engine; that was all the fuel we had left.”

The war also provided his introduction to Japan, where much of the U.S. military operation was based. “I remember walking down to the hangar on my first morning and an obaasan who was crossing the road said ‘Ohayo gozaimasu’ to me. That was my first exposure to the spoken Japanese language.”

After the Korean War ended, Pomeroy landed a posting to the Naval Attaché in Rome; years later he was to hear that it was thanks to the fact that the man giving out the assignments was the pilot of the downed plane in Korea, who recognized his name. In Rome, he studied Italian and Japanese, rode a Vespa, learned to make a martini, dated members of a visiting Takarazuka troupe and enjoyed the early days of la dolce vita. A Japanese diplomat he met there suggested he attend university in Tokyo, which eventually led to him graduating with a degree in Japanese language and Asian history from Sophia University in 1962.

“On my first morning an obaasan said ‘Ohayo gozaimasu’ . . . my first exposure to the spoken Japanese language.”

Pomeroy began working as a translator and freelance writer for local publications. One of his translation jobs led to a longstanding fascination with Japanese woodblock prints, which he had to learn in order to complete the translation. A Sophia connection at the FCCJ led to work as a correspondent covering the healthcare industry, a field that was to remain his mainstay until retirement in 2004. With bilingual correspondents a rarity in those days, Pomeroy was offered a position in the Tokyo bureau of UPI, but he declined. He was happy with his niche, which allowed him to meet top medical professionals as well as travel around Japan.

In the ensuing decades, Pomeroy found time to write a number of books, as well as compiling Foreign Correspondents in Japan: Covering a Half-Century of Upheavals: From 1945 to the Present, a history of the first 50 years of the Club, with leading members writing about a decade each.

Following his retirement, Pomeroy moved to his wife’s hometown of Otsuchi in Iwate, where they had built an expanded family home with a studio to indulge his passion for woodblock printing. March 2011 changed all that. Pomeroy and his wife happened to be in Tokyo when the earthquake and tsunami struck, killing members of their family, destroying the house and devastating the town. They are waiting for the ground in the town to be raised by 2.5 meters before rebuilding their house in 2018.

At the end of 2014, Pomeroy published Tsunami Reflections Otsuchi Remembered, a book he authored about the experience. “It’s not so much a book about the tsunami, but about life in Japan in a small port town, family relationships and how real people live in Japan.”

The summer after the tsunami, flowers began to grow around the ruined house. “We knew they were the flowers that Yuji had brought over from next door when we were first doing the garden,” Pomeroy says, recalling his wife’s brother-in-law, who perished in the disaster. “We took some of them back to Tokyo with us and put them on our veranda.” He says a reader of his book emailed him to say how struck she was by the symbolism.

“It was symbolic: life goes on.”

Gavin Blair covers Japanese business, society and culture for publications in America, Asia and Europe.