Issue:

Is “collective defense” necessary or a shift toward a more aggressively militaristic Japan?

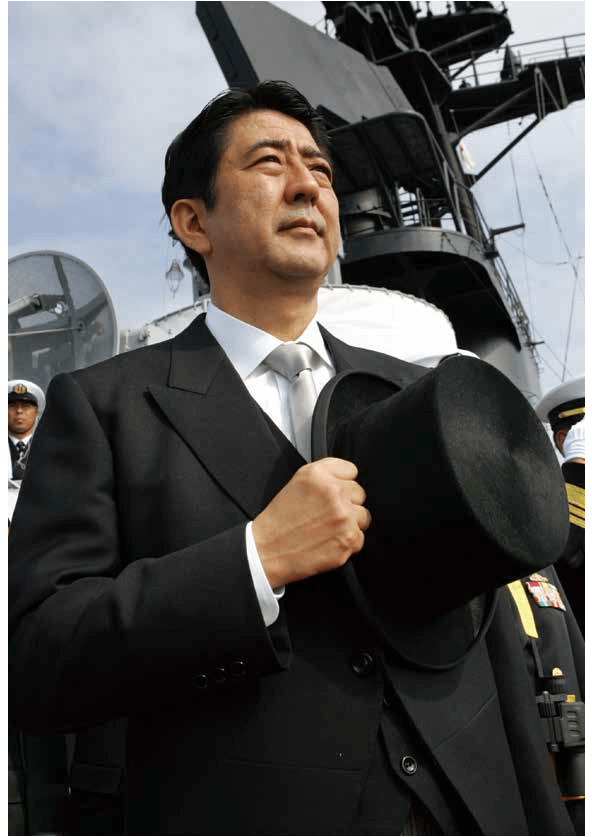

AP PHOTO/ITSUO INOUYE

Imagine this scenario: a lightly armed U.S. Navy intelligence gathering ship cruising off the coast of North Korea is suddenly surrounded by DPRK patrol vessels demanding its surrender. Only a few kilometers away, a destroyer belonging to the Japanese Maritime Self-Defense Force (the Japan’s navy) happens to be cruising close enough to offer help.

The prime minister must make a quick and agonizing decision. Does he order the destroyer to the rescue of a friendly vessel in harm’s way, thereby violating the constitution, breaking the law and possibly exposing the ship’s captain to criminal charges if any North Korean is killed? Or, should he obey the law, restrain the captain and almost certainly destroy the alliance with the nation’s main protector?

This scenario is by no means far fetched. A lightly armed U.S. Navy vessel, the U.S.S. Pueblo, was waylaid by the North Koreans and seized in January, 1968. The only difference is that there were no Japanese naval vessels (or American naval or air assets, for that matter) close enough to help the Pueblo when it was surrounded and captured.

Yet it is this kind of scenario that lies behind the renewed push to pass the necessary changes to the Self-Defense Forces Act that would permit Japan to engage in what’s called “collective self defense.” Briefly, it refers to a country coming to the aid of an ally when it is under attack and the country is in a position to help out. For years the Japanese government has interpreted collective defense as going against the country’s war renouncing constitution.

The U.S.-Japan security arrangement is often called an “alliance.” It is not. The term alliance is purely a courtesy title. The so-called alliance is, in essence, a deal. The U.S. promises to defend Japan if it is attacked, with nuclear weapons if necessary (the nuclear umbrella). In return, Japan agrees to permit American bases on its soil for Americans to use basically as they see fit.

However, Japan is not obligated to defend the U.S. if she comes under attack. The most commonly mentioned scenario intercepting a North Korean intercontinental ballistic missile fired over Japan on the way to the U.S. mainland is considered by most observers as far fetched. The “Pueblo scenario,” of rendering assistance to U.S. Navy ships if needed, is a more likely contingency.

The main practical emphasis behind a push to approve collective defense is Japan’s rapidly expanding involvement in United Nations Peacekeeping Operations. In the past 20 years, more than 8,000 Self-Defense Force troops have been involved in PKOs in half a dozen countries. Engineering troops are currently stationed in South Sudan, and army medical personnel help in earthquake ravaged Haiti. The navy takes part in anti piracy patrols in the Gulf of Aden.

The 2007 changes to the Self-Defense Forces Act made participating in U.N. approved peace operations one of the main missions. But it did not address such issues as lending assistance to other nations participating in the joint operations. So now Japan cannot come to the assistance, say, of an NGO targeted by terrorists, for example, or help a non Japanese ship attacked by pirates based in Somalia.

“The SDF is literally crossing its fingers that nearby friendly units won’t come under attack,” says Yuichi Hosoya, a law professor at Keio University. Other naval vessels on anti piracy patrol avoid getting too close to Japanese vessels, he said. “It’s too dangerous.” That Japan has never been in a quandary over protecting is colleagues on anti piracy patrol “has been sheer luck.”

Earlier LDP administrations had sought to modify the current restrictions against collective defense, but they were in office for too short a time to accomplish anything. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s recent remarks to the effect that he is in no rush to enact the change probably comes from a realization that the current government, still enjoying 60 percent plus approval ratings after eight months in office, is in power for a long stretch.

Currently, two special committees have been convened to consider aspects of Japan’s future security posture. They are expected to make their recommendations later this year for introduction to the Diet next year. One is the Advisory Panel on Reconstruction of the Legal Basis for Security, dealing with the collective defense issue. The other is the Advisory Panel on National Security and Defense Capabilities.

Additionally, the Diet will consider two security related bills in the current special session that began in October. This includes a law to create a National Security Council similar to the American NSC, and a projected doubling of the penalties for leaking classified information. Washington considers the current regulations too slack, obliging it to withhold certain sensitive information.

The panel on National Defense Capabilities is separate from the collective defense panel and looks into other issues such as the question of permitting preemptive strikes against a country (say North Korea) that it believes is preparing to launch a missile attack against Japan. Another issue under study is the advisability of creating a marine corpslike branch of the ground forces to defend or, if necessary, retake Japanese islands south of Okinawa.

These could possibly be considered offensive capabilities outlawed by Article 9 of the Constitution. On the other hand, the Defense Ministry specifically defines proscribed offensive weapons systems as being Intercontinental Ballistic Missiles, long range bombers and aircraft carriers. It does not mention cruise missiles, troops trained in amphibious assaults or aerial refueling aircraft.

Put this all together and it seems to herald a significant shift toward a more militaristic Japan. That, certainly, is how many would interpret it, since these measures would gut the war renouncing Article 9, destabilize the regional security environment, irritate China and drag Japan into American inspired conflicts it has no desire to take part in.

Changing aspects of Japan’s security posture

Guidelines for Japan-U.S. Defense Cooperation A planned revision of the bylaws that determine each country’s security role in peacetime and in war, last revised in 1997, to reflect changing realities in Northeast Asia. Due by end of 2014.

Advisory Panel on Reconstruction of the Legal Basis for Security The committee looking into legal aspects and constitutionality of collective self-defense. Report due end of 2013 with necessary laws enacted or amended in 2014.

Advisory Panel on National Security and Defense Capabilities A separate committee looking into possible preemptive actions by the armed forces such as creating a marine corps like unit of the ground forces. Report due by end of 2013 with revisions adopted in 2014.

Legislative Initiatives in Current Diet Session A bill to establish a National Security Council patterned on the American NSC and establishing more severe penalties for civil servants who leak classified documents.

Or, it may simply be recognizing the changing security circumstances in Northeast Asia, including North Korea’s nuclear weapons and China’s growing military and its intransigence over the disputed Senkaku islands. Speaking at the first session of the Defense Capabilities panel in September, Abe said: “I will proceed with the rebuilding of a national security policy that clearly addresses the realities facing Japan.”

The prospects of any of this being enacted are uncertain. The current relatively short Diet session is crammed with many potentially contentious issues, mostly related to the government’s economic program. There may be opposition from the LDP’s parliamentary coalition partner, New Komeito, which is more pacifistic. But at the moment the government has the luxury of time.

Todd Crowell was Senior Writer for Asiaweek from 1987 to 2001, and is the author of Who’s Afraid of Asian Values.