Issue:

August 2023

One weekly’s account of the Meriken-goro murders that scandalized early 1900s Washington State

The earliest Japanese immigrants to North America, in general, earned a well-deserved reputation for being honest and law abiding. A few, however, were not. In the years before World War I, certain less-than-upstanding members of Japanese immigrant communities acquired the sobriquet Meriken-goro – Meriken meaning American, while Goro is shortened form of gorotsuki, a racketeer, hoodlum, rogue or hooligan.

The Meriken-goro who figure in this story have been described in terms somewhat similar to the bakuto (professional gamblers who were forerunners of the yakuza) during the late Tokugawa period (1603-1867). Unlike the bakuto, however, these men were not guided by a sense of honor or chivalry. Still, similarities existed in that they were composed of bosses and their henchmen, and staked out territory and engaged in turf wars in which injuries and killings between rival factions were common.

A long-term resident of Seattle named Kozo Koyama, who worked at various jobs including legal translator and interpreter, penned a fictionalized account of a crime spree by such individuals that appeared in Shukan Asahi on August 11, 1936.

Koyama's story concerns the murders of several Meriken-goro in Washington State in autumn 1913. Most of the perpetrators were apprehended, tried and sentenced in U.S. courts, but the main instigator fled to Japan. Rather than being extradited, he was tried and convicted in Japan, reportedly the first person to have been treated under a new provision in the criminal code that enabled courts in Japan to prosecute Japanese nationals who committed crimes abroad.

Koyama begins his account in Shukan Asahi with the observation that, “Without women, men are brutal” - as evidenced by the many bloody incidents that occur in immigrant areas where women are scarce.

This episode centers on the hamlet of Walville, in the U.S. state of Washington, located about 150 miles south of Seattle. It had already been abandoned by the 1930s, but in the first decades of the 20th century, it was home to a lumber camp and sawmill that employed more than 100 Japanese workers. The boss of the Japanese contingent was a native of Kochi Prefecture named Mitsui, who, according to local news reports, “ruled the Japanese colony with an iron hand”.

“No one would work in the mill unless Mitsui willed,” reported the Evansville Press on March 30, 1914. “He extracted toll of all. He settled disputes, and his word was law. He rewarded or punished as he pleased.

“Mitsui was the leader of as motley a band as ever slit a throat to turn an honest penny.”

Mitsui had earned the status of being "Walville's Big Brother" because of his various ties with Meriken-goro in Tacoma and Seattle.

Mitsui cohabited with a woman named Okane, said to be a former prostitute and with a reputation for being a woman of loose morals. After Mitsui set up housekeeping with Okane, his thuggish behavior was said to have become even more extreme.

One day, a man named Koyama, a hoodlum on the run from several violent incidents in Seattle, arrived in Walville and asked Mitsui to shelter him. Koyama had a reputation for being short-tempered and overbearing.

The two were joined by a third man, named Nakashima, a Tacoma-based tough. It seemed that Koyama and Nakashima had quarreled over a woman in the past, with Nakashima coming out on the losing end. Mitsui was not pleased to learn of this and sought to help Nakashima take revenge against Koyama.

That night, at Mitsui's cabin, things came to a head.

Mitsui summoned Nakashima into the bedroom, saying, “Nakashima, you've got no backbone. Kill him!”

Pulling a pistol from a bureau drawer, Mitsui forced it into Nakashima's hand and Nakashima turned back into the guest room as if possessed.

“Koyama! You son of a bitch!” he shouted, firing wildly at Koyama.

Koyama flung away a glass of whiskey he was holding and was immediately hit by gunshots. With a moan, he fell to the floor.

Miyagawa and Hashida, Mitsui's two henchmen, and Okane were startled by this sudden turn of events, but they could not have foreseen the consequences of Koyama's slaying.

One of Mitsui's underlings, Miyagawa, patted Nakashima on the shoulder as he stood there, lost in thought, and said to him, “You killed him, eh? Good work!”

Shot in the chest, Koyama was sprawled on the floor, his shirt stained with blood. He had stopped breathing.

“Hey, how do we take care of this?” Hashida asked Mitsui.

“Take him out to the mountain and bury him,” Mitsui ordered.

The following night, taking advantage of the darkness, the four men carried Koyama's body to a spot in the mountains some distance away, where they dug a grave in the sand at the foot of a cliff and buried him.

After burying Koyama, Nakashima returned to Tacoma for a while, but feeling emboldened after having killed a man, he began to run up gambling debts, often returning to Mitsui for a new stake. He became increasingly pugnacious, and his efforts at extortion became more demanding. Finally, Mitsui decided he needed to get rid of this troublesome man.

After consulting with Hashida and Miyagawa, Mitsui lured Nakashima out into the mountains one night under the pretext of reburying Koyama's body. Mitsui and Miyagawa shot him dead. Nakashima was buried alongside Koyama at the foot of the cliff.

In Walville, where the two crimes had taken place under the cover of darkness, there was initially no hint of anything suspicious, but after Nakashima's disappearance rumors began to spread among Tacoma's gangsters. A Meriken-goro from Seattle named Deguchi heard things via the grapevine and called on Mitsui in Walville with the intent of putting the squeeze on him.

Four or five days earlier, a man named Yamamoto, who had been paroled from the Washington state reformatory at Monroe, had taken up temporary lodging with Mitsui. The two both hailed from the same town in Japan.

Yamamoto was known to be a dangerous man, and he and Deguchi were said to get along “like dogs and monkeys,” i.e., they disliked each other intensely.

Deguchi seemed to have figured out about Mitsui's two earlier killings, leading Mitsui to feel increasingly nervous. He decided to persuade Yamamoto into shutting Deguchi's mouth permanently.

Yamamoto, who had long felt indebted to Mitsui, readily agreed to cooperate and promised to get rid of Deguchi for good.

Mitsui waited for Yamamoto to appear in the guest room where he had earlier killed Koyama, with Hashida and Miyagawa at his side.

Yamamoto came in affecting a casual air, but at the moment he saw Deguchi he suddenly pulled out a pistol, saying,

“’Degu’, you came here knowing this was going to happen, didn't you?”

In the years that followed, Yamamoto would kill many others. Each time he habitually mocked them as they agonized in his clutches, having been caught unawares.

Deguchi, perhaps sensing his inescapable situation in the midst of the group's excitement, begged Yamamoto for mercy. Assuming an air of amusement, Yamamoto stretched out his long arms, grabbing Deguchi's shoulder, as he said, "He, he, he, this is farewell. Take a moment to reminisce as much as you can, of your parents, your brothers and me. Ten seconds from now, everything will go dark.”

Just as Deguchi boldly reached for his own pistol, Yamamoto fired. The first bullet wounded Deguchi, and as he stumbled on his feet, a second bullet pierced his skull, killing him.

Deguchi's body joined the other two men at the foot of the cliff.

In December 1913, Mitsui set sail from Tacoma to Japan aboard the Arabia Maru. Upon his arrival in Japan, the two bloodhounds he had brought with him were blocked by animal quarantine authorities and, ironically, he wound up donating them to the Tokyo Metropolitan Police Department.

Upon his return to his hometown in Kochi, Mitsui spent many days carousing in geisha houses and enjoying the pleasures of life.

Back in the U.S., Deguchi, the last of the three to have been killed at Walville, had a younger sister who was married to a businessman in Seattle. Fretting about her brother's fate, the sister dreamed she saw her brother's bloody corpse. Her anxieties were further stirred when she heard rumors of troubles in Walville. She filed a missing person’s report with South Bend County authorities, which had jurisdiction over Walville.

With two assistants in tow, the sheriff of South Bend traveled to the Walville sawmill unaware that three murders had taken place there. Yet, when questioned by the sheriff, Miyagawa and Hashida readily confessed. The sheriff immediately placed the two men and Okane under arrest, but Yamamoto, armed with two rifles, had already fled deep into the mountains.

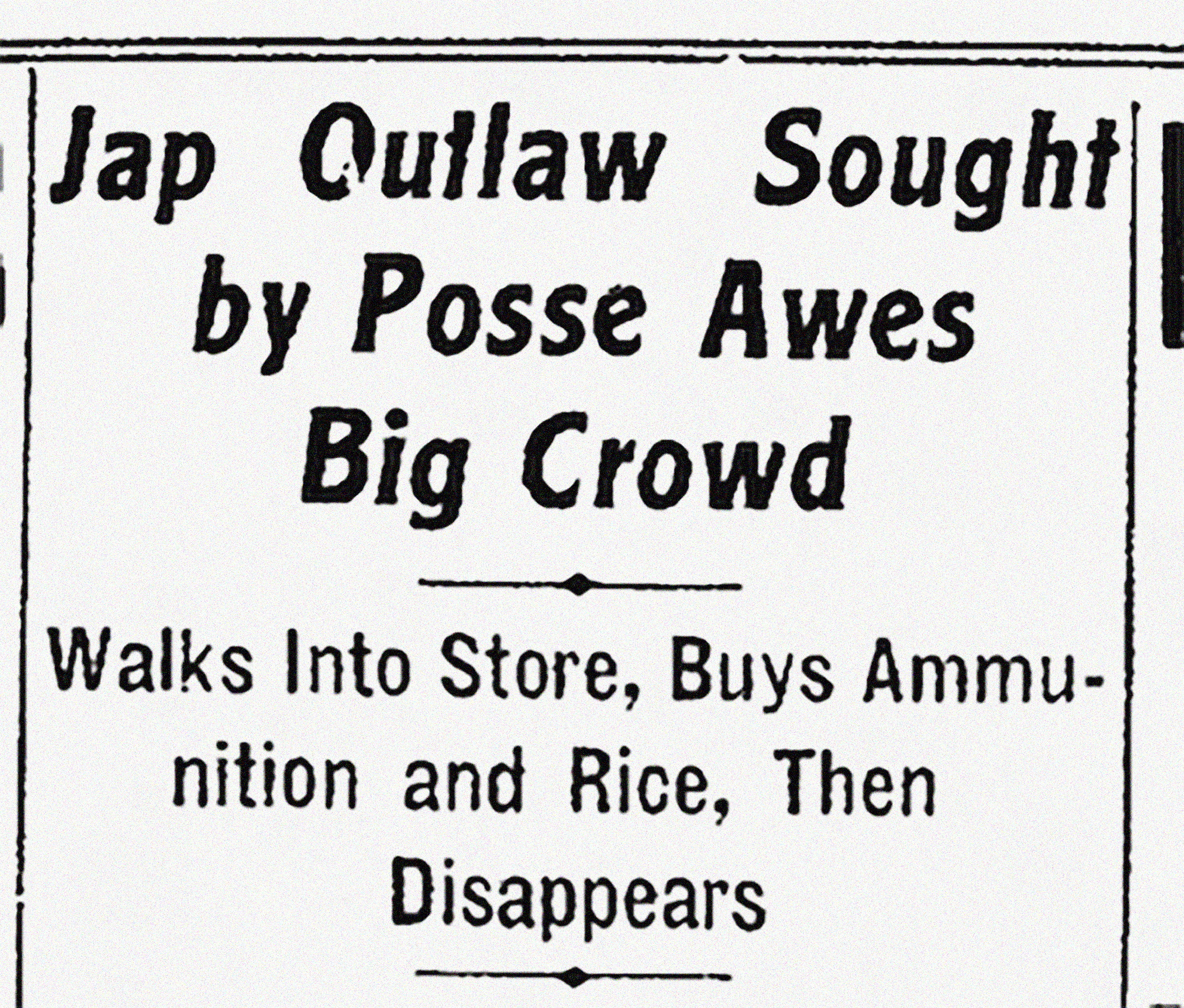

Following the medical examiner's inquiry, Miyagawa, Hashida and Okane were formally indicted for the murders. Yamamoto, apparently unaware that he was wanted by the law, was last seen walking into a dry goods store with his dog, where he bought rice and ammunition, and then rode off into the mountains. More than a dozen policemen formed a posse to track him down, but further details are scarce.

At their trial, Miyagawa and Hashida were sentenced to 15 and five years, respectively. In exchange for her witness testimony, Okane eluded punishment, although she may have been subsequently deported.

The question then arose as to whether or not to extradite Mitsui from Japan, which was possible under the extradition treaty. To do so, however, would cost the state a considerable amount of money. County officials approached Seattle's Japanese consul-general Seiichi Takahashi, who advised them that Japan's criminal law provided for punishment of crimes committed overseas.

The South Bend County court's report detailing the triple murders was thus forwarded to the Japanese consulate and from there to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Finally in March 1915, the Tokyo Metropolitan Police sent a telegram to the Kochi Police Station ordering Mitsui's arrest.

Mitsui, who had been apprehended while asleep in his newly built house, stubbornly denied the murders, but the testimonies of Okane, Miyagawa, and Hashida left no question of his involvement.

The Kochi District Court sentenced Mitsui to 18 years in prison. The Osaka Court of Appeals rejected his appeal and upped his sentence to life imprisonment. At the time of his Shukan Asahi article in 1936, Koyama was unable to determine Mitsui's fate.

The law concerning extraterritorial jurisdiction over crimes by Japanese nationals abroad still remains in force. In one recent celebrated case, businessman Kazuyoshi Miura was arrested, tried and convicted on a charge of attempted murder of his wife, Kazumi, while in Los Angeles. Based on the testimony of Michiko Yazawa, a former bus guide and pornographic actress he had befriended, Miura had persuaded Yazawa to attack Kazumi with a blunt object on August 13, 1981, while in her room at the Hotel New Otani in Los Angeles. Four months later came the shooting incident during a staged robbery in downtown Los Angeles that would result in Kazumi's death.

Miura was never convicted of those charges, either in Japan or the U.S. His death in Los Angeles in October 2008 while on arraignment, following extradition from Saipan, Marianas Islands, was ruled as suicide.

A translator, columnist, author and mystery fiction enthusiast, Mark Schreiber has lived in the Far East since 1965.