Behind many great works of art are dark stories about their creation, and The Ondekoza is no exception. Gracing the FCCJ with his presence — despite having skipped the first two screenings of the film, at the Venice and Tokyo Filmex festivals — Ondekoza’s star, taiko pioneer Eitetsu Hayashi, spoke eloquently about the genesis of the musical group and the eponymous film that pays tribute to its extraordinary accomplishments. There is no hint on screen about its true backdrop: that of a powerful mentor and his cruel exploitation of the young.

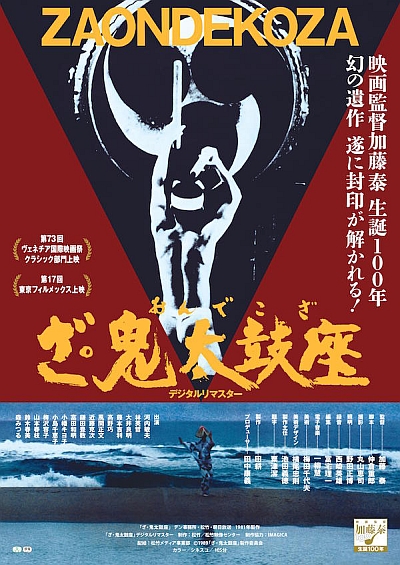

Thirty-five years after its heralded premiere and subsequent disappearance from public view, the musical masterpiece The Ondekoza now returns in a blaze of cinematic glory, thanks to Shochiku, which first commissioned the documentary in 1979, and has now digitally restored it, in 4K, to mark the 100th anniversary of the birth of its director, Tai Kato (1916-1985).

Kato had begun shooting in 1979 and continued for two years, following the young people who had formed the Ondekoza Japanese music ensemble in 1971 on Sado Island, north of Niigata, under the leadership of Tagayasu Den. The teens had been lured north by Den’s plan to build a liberal arts college on the island, and had decided, despite their lack of musical training, to raise funding by performing updated versions of Japanese standards, particularly by forming a tight unit of taiko drummers.

Hayashi generously detailed his behind-the-scenes experiences. ©Mance Thompson

The first half of The Ondekoza follows the group’s daily routines, as well as the rehearsals and concerts in local halls, and the efforts to adapt traditional folk pieces to fit their burgeoning repertoire. They live communally, work and train together in Spartan conditions, craft their own instruments, create their own choreography and sew their own costumes. They run together, too, building up physical stamina, as they traverse many miles across the island’s rugged terrain. (They would go on to run the Boston Marathon each year from 1975 – 1981, playing drums immediately after crossing the finish line.)

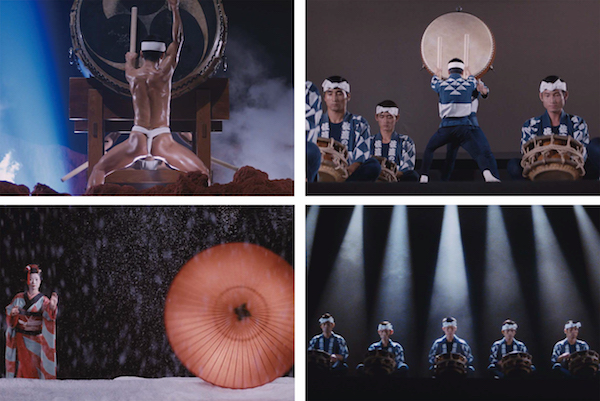

In its second half, the film positively explodes in vivid colors across the screen, as the group performs a series of dazzling setpieces — many on sets designed by legendary designer Tadanori Yokoo and Chiyo Umeda — including Devil Sword Dance (Oni kenbai), O-Shichi of the Tower (Yagura no O-Shichi), Changing Cherry Blossom Song (Sakura Hensokyoku), The Big Taiko (Odaiko), Monochrome II (Monokuromu II), Float Orchestra (Yatai bayashi) and Tsugaru Shamisen (Tsugarujamisen). Kato’s unique camera techniques heighten the visual brilliance of the numbers, capturing the performers as they achieve astonishing levels of virtuosity, transforming the screen into a perfect expression of art’s transcendent power.

©1989 "The Ondekoza" Film Partners

Perhaps the film’s most spectacular sequences involve scenes of drummers, clad in loincloths, beating enormous taiko drums, encircled by leaping flames of hellfire. While most people assume that groups of drummers playing together in disciplined unison is the Japanese tradition, it first occurred after WWII. Eitetsu Hayashi himself is credited with originating the wadaiko form, in which a carefully choreographed group (like those in the film) plays large taiko drums, often with their backs to the audience for greater dramatic effect.

Speaking at the Q&A session following the screening, which he had watched, Hayashi explained, “In the 1960s, I was a huge Beatles fan and had my own amateur band. Since I had that experience and a sense of rhythm, I wound up supervising the drum sequences in the film, and composing the music for them. Usually with musical films, you record the music first, then you lip synch and match the dancing to the music. But the director wanted to shoot everything live. We only had one camera, so we had to shoot [again and again] from various angles. With wadaiko, there’s a lot of intensity when you play, and you’re working up a sweat. When you cut to shoot from another angle, you have to work up to the same intensity again, so I had to play the entire piece from the beginning each time. It was a very strenuous shoot.”

Hayashi demonstrates the now-familiar taiko drumming stance, with sticks up above the head. ©FCCJ

After spending 11 years with the Ondekoza, Hayashi would go on to cofound the globally acclaimed taiko troop Kodo, before commencing a solo career. He has since moved from one triumph to the next, beginning in 1984, when he became the first-ever solo taiko performer to play with the American Symphony Orchestra at Carnegie Hall. Renowned for his virtuosity, his physical stamina and his range, which fuses traditional, classical, jazz, rock and world music, his performances have influenced such popular musician- percussionists as the Blue Man group and Stomp.

But before the flourishing career and the happy circumstances that have finally brought about the release of The Ondekoza, there was the agony. Hayashi admitted, “I had qualms about coming here to see it tonight. It took a lot of courage for me to watch it again. It reminds me of those days when we were putting our heart and soul into our performances … not knowing that the film would not be released. My life changed drastically after that.”

Pressed to elaborate, he told the audience, who sat transfixed throughout, “What you see up on the screen may seem like we came together for the love of art, and aspirations to become great performers, but that’s not the case. We didn’t set out to become professional musicians, but the leader of the group [Den] was very strong, very determined, a bit of a dictator. He’d been one of the students who led the student protests [at a university in Tokyo], and he was draconian. He did not allow any TV, radio or newspapers, we weren’t free to spend time with friends outside the group, we were not paid, we did not have any vacations or time off.

Nakagawa, manager of Shochiku’s Home Entertainment & Licensing Division, is the man responsible for working to clear the myriad copyright and other issues that had prevented the film from being shown more than a handful of times since 1981. ©Mance Thompson

“It was our duty to listen to whatever he had to say, and to follow his orders. But we thought the money we were earning [from performances] was going to the establishment of the college. It was an honor, back then, to earn money overseas, and we were grateful to him. However, he gradually changed his mind. The college never came to fruition. And the group became like a cult. As cults go, as dictatorships go, it was impossible to escape. We had no money, no boats, so we couldn’t leave.

“We were increasingly gaining attention overseas — even Seiji Ozawa, who was conducting the Boston Symphony Orchestra then, invited us to appear together in 1976, and we won many accolades. After that, we started to perform in very large venues, going on tours, even appearing on Broadway. At that point, the leader thought, ‘We should make a film about ourselves and take it to the Cannes Film Festival, to show how successful we’ve been overseas.’

© FCCJ

“So a large amount of money was borrowed to make a film. But once it was completed, the leader said, ‘I don’t like this film. I’m going to direct my own film.’ There was no means to return the money we’d borrowed to finance it, and no way to continue operations with the Ondekoza. The group members finally voiced our concerns, and the dictator that he was, he said, ‘You’re all fired.’ So the group ultimately dissolved, which meant that Shochiku couldn’t release the film.”

Before Hayashi provided this painful context for The Ondekoza, the FCCJ audience had been able to experience the film’s lasting artistic achievement without the shadows cast by its backstory. That the backstory has now deepened their appreciation is beyond a doubt; but its troubling questions linger, much as they did in Damien Chazelle’s 2014 Whiplash, another film about a mentor’s monstrously autocratic abuse of musicians, particularly one young drummer, and the toll that it takes upon his soul.

Hayashi and Nakagawa pose with one of the three remaining original posters for the film (right), designed by Tadanori Yokoo.

©Mance Thompson

©1989 "The Ondekoza" Film Partners

Posted by Karen Severns, Friday, December 16, 2016

Read more

Published in: December

Tag: Eitetsu Hayashi, Sado Island, taiko drums, documentary

Comments