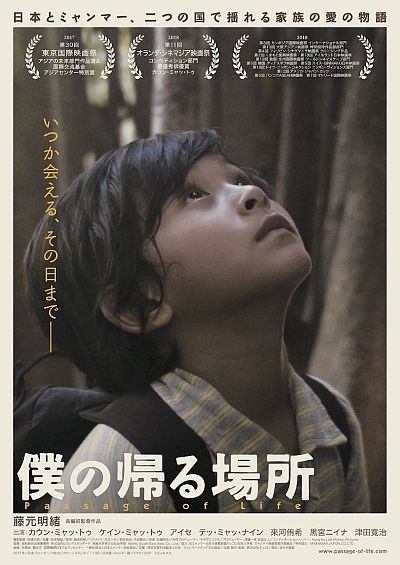

The line between fiction and reality is blurred in Akio Fujimoto’s debut feature, Passage of Life. A poignant family drama with an undercurrent of political urgency, the Japan-Myanmar coproduction won both the Spirit of Asia Award and the Best Asian Future Film Award at the 2017 Tokyo International Film Festival — the first time a Japanese director had been so honored.

It went on to screen around the world to critical accolades, winning awards in the Netherlands and Thailand (where it qualified as a Burmese film). Just last month, it also received a Special Recognition honor from Japan’s Education Ministry, meaning that it is recommended for school viewings. As the awards season looms, there is every expectation that Passage of Life will be on many year-end lists.

The domestic accolades are especially important, since there are surprisingly few contemporary Japanese fiction films that incorporate pressing social issues into their storylines, and fewer still that treat non-Japanese characters (who barely seem to exist on screen here) with understanding or real compassion.

©Mance Thompson

At the Q&A session that followed the FC’s sneak preview, producer Kazutaka Watanabe explained the film’s genesis, way back in 2013: “The idea [to depict Burmese immigrants] came from Yuki Kitagawa, who appears in the film as the Japanese man who’s helping the family, and who also became the film’s co-producer. We had no money, and I didn’t have any experience as a producer yet, but we decided to go ahead with the project. Most of the information about Myanmar online is about the military government and Aung San Suu Kyi, not about the daily lives of Burmese. We wanted to tell a story that Japanese audiences could empathize with, that could also be full of discoveries. So we put out a monthlong open call for writer-directors online, and had about 40 responses. Mr. Fujimoto was the only one who wrote an entire script in that month, and he was also one of the most passionate. We were really impressed that despite his limited knowledge of Myanmar, he was able to create a believable world.”

Fujimoto conducted his initial research in Takadanobaba, which has one of Tokyo’s largest Burmese populations, and decided to portray one of the hard-luck stories he’d heard. He didn’t realize that his script would have to be vetted with the Myanmar government, nor that a representative would be on set during the shoot there. But despite the censorship, the film’s family can be seen as a metaphor for every family that has and is still facing an uncertain future.

Kaung contemplates life in Myanmar. ©E.x.N K.K

Passage of Life drops us without preamble into the lives of Issace (Issace) and Khin (Khin Myat Thu), who immigrated to Japan from Myanmar without visas, along with their two sons, Kaung (Kaung Myat Thu) and Htet (Htet Myat Naing). They were following in the footsteps of many others, who began coming here in the wake of the 8888 Uprising (1988 pro-democracy demonstrations) in Myanmar. (There is briefly-seen newsreel footage of brutal military clampdowns on protestors.)

Issace and Khin find illegal work in Tokyo and create a happy life with their boys — although Kaung, now 7, and Htet, 4, believe they are Japanese and have the attitudes to go with it (“Idiot!” yells Htet, nearly hitting his mother in one fit of pique).

After several years of residency, Issace learns it is possible to file an application for political refugee status, and during his interview with Immigration, explains they left their country because “it was no longer safe.” But the request is denied, as happens all too frequently here, and no clear explanation is given. Issace tried to reassure Khin, who is struggling with an unnamed illness, but she pleads with him to return to Myanmar before their re-application is rejected again. “Things have changed back home since we came,” she says hopefully. “No way,” he responds. “Things can’t be that different. There’s no way we could back.”

Kaung gets lost enroute to the airport. ©E.x.N

Then one night, Immigration shows up at the door and warns Issace to stop working. Khin says, “We can’t be safe, not even in our own home… coming here was a big mistake. I want a normal life.”

After a hospitalization and with options fast dwindling, Khin makes the choice to takes the boys to Yangon, where they will grapple with their loss of friends and Japanese identity — as well as their distance from Issace, who has stayed in Japan to continue working so he can send them money. But Skype calls are not the same as being there, and one day, Kaung packs his rucksack, grabs a toy gun and heads for the airport.

©FCCJ

Despite the film’s impressive social-issue immediacy, the initial Q&A questions focused on the extraordinary performances of the two small boys. Noting that it was the one thing he had been asked everywhere he traveled with the film, Fujimoto said, “No matter what nationalities the audiences were, everyone seemed to empathize with Kaung and this family. That made me really happy.”

He continued, “The most difficult part was that this was not an actual family, so the challenge was how to make them as real as possible. Since the father is not the boys’ real father, we had to figure out how to build a loving relationship between them. Khin-san [Khin Myat Thu] is their real mother, but the father is a Myanmar-based [stranger]. It was very difficult for the boys to call him ‘Papa’ at first.”

Fujimoto laughs as Myat Thu recalls mock-fighting with her son. ©Koichi Mori

Myat Thu, who has lived in Japan for 18 years, and whose sons were raised here, signed on to portray the mother when her elder boy, Kaung, decided he wanted to be in the film. She recalled, “The most challenging part of the process for me was the scene in which Kaung and I had to have a fight. That never happens in real life, so we had to find a way to fight realistically, and that was difficult.”

To capture a high degree of authenticity from the children, Fujimoto decided to shoot lengthy takes without interruption, and then spent 2 years editing down the resulting tens of hours of footage. He was asked why he had adopted the film’s documentary-like shooting style. The director answered, “It’s difficult to lock down the camera when you’re shooting children, unless you direct them to move in a restricted way. We wanted to have them move freely, and to have the camera move freely along with them.”

Mom and the two boys explore the forests outside Yangon. ©E.x.N K.K

Fujimoto also said he had accepted a certain degree of improvisation from the children, as long as the meaning of the original dialogue did not change. “We were extremely lucky, because although the younger boy, Htet, couldn’t read the script, he didn’t veer too far from it. But there was a certain scene in which he cries profusely, and that wasn’t included in the original script. It was supposed to be a very heartwarming scene, but when I explained what was happening [in the story] before the camera rolled, he just burst into tears.

“The original plan had been to tell the story of the older brother, Kaung, and [his coming of age]. We shot in sequence, and I was quite happy with how things were going. But thanks to [Htet’s outburst], it created a sudden juxtaposition with the younger boy’s own growth, or coming of age.”

Watanabe and Fujimoto. ©Koichi Mori

Asked what he thought the film’s main message is, producer Kazutaka Watanabe replied, “What I found most impressive is that we had a Japanese director who was able to empathize with Burmese children. I feel that’s a rarity here — most creators don’t seem to feel empathy for people from Southeast Asian, or any foreigner, for that matter. Of course immigrants coexist with us in Japan, you see them working in convenience stores and family restaurants. But there’s no empathy. If we manage to get the audience to empathize with characters like this, we can expose them to something different. Of the film’s many messages, I think that’s the most important.”

Another journalist asked the director why Passage of Life was vague about the reasons that Isaace’s application for refugee status had been rejected. “It was intentional not to include too much exposition, or to give the background for why they had come to Japan in the first place,” responded Fujimoto. “This was a point I thought a lot about, but I ultimately decided to pare down those details. I could have given some explanation of why the system in Japan is so complicated and so strict. But what I really wanted to do was to show to daily lives of these people from their viewpoint.”

He added, “I think it’s probably very difficult even for professionals working in the immigration field to explain the reasons for a rejection, and it’s also difficult to prove that you’re a refugee. It would make me very happy if the film instigates discussion among immigrants in Japan.”

©Mance Thompson

There are an estimated 10,000 Burmese currently here on legal visas, although watchdog groups suggest there are many more undocumented immigrants (from many nations) than the government’s official count.

Last year, Japan granted refugee status to only 20 people, out of nearly 20,000 applicants (a sharp increase over the previous year’s applications). The year before, it approved just 28. The Justice Ministry started a stricter screening system in January this year to eliminate applicants believed to be purely job-seekers, and reported in late August that applications had plunged 35% in the first half of 2018 (22 applicants were approved).

But Japan has not officially adopted an immigration policy, and as security is beefed up ahead of the 2020 Tokyo Olympics, the government is cracking down on those working illegally while awaiting the outcome of their refugee applications, putting them in detention centers and creating the sense that every visa overstayer is a criminal.

In a perfect world, every Japanese would watch Passage to Life and help, somehow, to implement correctives.

©E.x.N K.K

Posted by Karen Severns, Saturday, September 22, 2018

Read more

Published in: September

Tag: Tokyo International Film Festival, awardwinning, immigrants, refugees, Myanmar

Comments