On April 19, 2012, corporate whistleblower Michael Woodford appeared at FCCJ, just a day before his former employer’s annual shareholders meeting. “The Olympus scandal would have been a wonderful opportunity to really get it right,” he told an enormous crowd of reporters. “All they’ ve done is make it worse. Olympus may get away with it, and the institutional shareholders, after sweating tomorrow, may be fine with it. But the damage is done. Would you invest in Japan? Do you believe in the integrity of company accounts?”

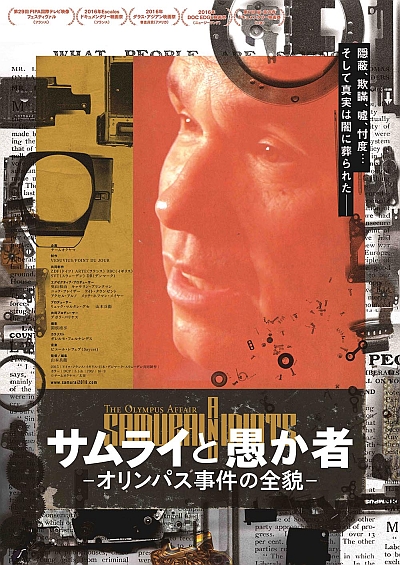

In Samurai and Idiots — The Olympus Affair, Woodford and other eyewitnesses demystify one of the biggest corporate governance debacles in postwar Japan (it was neither the first nor the last). An engrossing case study of a documentary, it is finally being released in Japan some 3 years after its heralded UK premiere, and some 5 years after Olympus was fined ¥700 million ($6 million) and its three top executives plead guilty to massive accounting fraud.

Watching it all unfold, as director Hyoe Yamamoto forensically peels back layers of the onion to reveal more rot within, is jaw-dropping stuff.

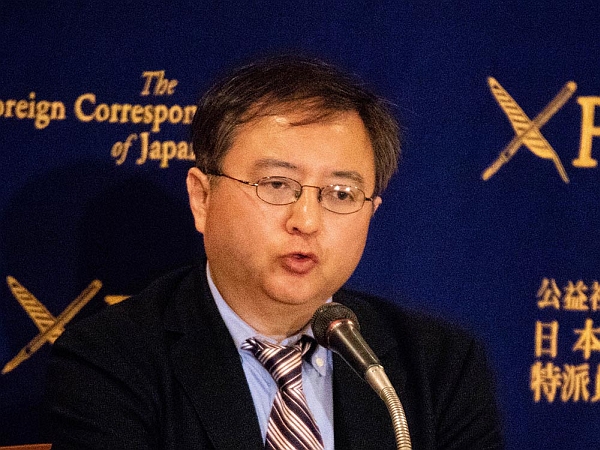

At top, Yamamoto and Soble ©FCCJ; bottom, Miller and Yamaguchi. ©Koichi Mori

But for the large contingent of financial and cultural reporters in FCCJ’s sneak preview audience, many buffeted by today’s impediments to truth- telling — from internet trolling to state secrets laws to presidential tweets — it was also a reminder that their work is absolutely essential. Samurai and Idiots is not just a dissection of corporate governance gone wrong, it is also a celebration of the courage and perseverance of journalists and others who support whistleblowers, sometimes at great personal risk.

In October 2011, Woodford had become the first non-Japanese appointed CEO of the multibillion-dollar optical firm, having "exceeded expectations" as Olympus president and COO for the prior six months. Just two weeks later, he was at the center of a widening uproar, having gone public when the board ousted him rather than answer his questions about $1.7 billion in fees that Olympus paid to and for what he termed “Mickey Mouse” companies (some with ties to organized crime), apparently to hide old losses.

Woodford had been tipped off by a series of articles written by Yoshimasa Yamaguchi in the bravely independent news magazine Facta. Woodford gave his own inside scoop to reporter Jonathan Soble, then at the Financial Times, the same day he was fired; and while Japan’s press toed the Olympus line (the foreign CEO had “failed to overcome cultural differences and communications difficulties” and “ignored the hierarchy”), the truth began exploding across global business pages.

Tracing the unfolding mystery from its beginnings, and presenting pithy data with a streamlined digestibility, Samurai and Idiots reveals that Woodford sparked an East-West cultural showdown that grew increasingly polarizing, and continued to be vilified, even after the corporate malefactors were finally arrested.

Michael Woodford gives his side of the story. ©Team Okuyama / Uzumasa

At the lengthy Q&A session after the FCCJ's sneak preview screening — which evolved into a master class in corporate governance, whistleblowing and deteriorating employee trust in today’s Japan — director Hyoe Yamamoto recalled, “One of our first major hurdles was how [to cover so many] technicalities and present this as a very simple story, so that people who may not have knowledge of how the financial world works will understand exactly what happened … We had a lot of discussions about where to take the film, and there were a lot of angles we could have covered. I felt my job as a storyteller was to make it as accessible to as many audiences as possible. It presents so many aspects of the ‘culture clash’ and what’s going on in the world right now.”

Yamamoto was joined on the dais by journalists Yoshimasa Yamaguchi and Jonathan Soble, and by Waku Miller, a longtime friend and adviser of Woodford — all of whom are expert talking heads in the film. They were asked what has changed in the years since the scandal broke.

“It’s said that the Olympus scandal was one impetus for new corporate governance rules that came into effect a couple of years ago in Japan,” responded Soble. “It’s probably worth noting that, on paper, Olympus had great corporate governance. The [new 2015] rules stated that you have to have independent directors on your board, but Olympus actually had that. In some ways, it’s a reminder that on paper, it can only go so far. Toshiba, which got into trouble recently for [hiding its profit-padding], on paper also had great corporate governance. There’s a debate right now in Japan about whether the new rules are good or bad, whether they go far enough or not, and that’s all very healthy. But I think it’s a reminder that the Olympus story is about how the rot inside a company goes beyond what you can do with rules on paper.”

Facta editor-in-chief Shigeo Abe, says, "Things haven't changed much since the feudal era...

Anachronistic practices are preventing needed reform." ©Team Okuyama / Uzumasa

The director concurred, adding, “I couldn’t put it in the film, but there was a lot of struggle between Olympus and the auditing company, Azusa, which [had pointed] out a lot of questionable dealings. After Azusa asked too many questions, Olympus switched to Ernst and Young [instead]. I’m assuming it was clear that shady deals were going on, and the auditors had to point them out. But obviously, Olympus decided to switch auditors at a curious [juncture].”

Yamaguchi cautioned, “If we start talking about the auditing, we’ll be here until tomorrow morning.” Waiting for the audience laughter to die down, he added, “Let me reassure you that the government is taking this seriously. The individuals in the industry, the CPAs and others in auditing firms, have a strong sense of urgency about the way they operate. But organizationally, we face what you’d have to characterize as systemic rot.”

Said Yamamoto, “All these rules and other systems were in place, but no one took a stand except Michael Woodford. I think that’s the important point. This could have been stopped. I can see this happening all across the board in Japanese society, and this is something we really need to confront and recognize. It’s happening everywhere, even now.”

But recognition doesn’t always lead to change. As Yamaguchi told the audience, “Seven years [after I wrote the initial articles], we find that Olympus has continued to engage in all sorts of shenanigans, including fraud in China and the employment of representatives of organized crime groups to facilitate that fraud, as proven by investigations conducted by multiple legal offices. So has Olympus changed? I would conclude No. The faces have changed in management, but the mindset has not. It makes me want to go after them with an endoscope [a reference to one of Olympus’ key products], to see what’s going on inside.”

Yamamoto marks his feature debut with Samurai and Idiots, which was produced by

Japan, France, Germany, Sweden and Denmark. ©Koichi Mori

Mentioning that Woodford had certain “luxuries” as the CEO that lower-ranking employees would not have had if they had blown the whistle, Soble said, “The idea that whistleblowers need some kind of protection is spreading. You see a lot of cases in Japan right now. A lot of the business news has been taken up with falsification of product quality data at companies like Mitsubishi Materials and Kobe Steel. A lot of that is coming from whistleblowers. Whether they’re doing that because they feel more protected, or whether it’s because the relationship between Japanese employees and their companies is changing and they don’t feel the loyalty that they used to, there are more people coming to authorities and speaking out than there used to be. Olympus was definitely a catalyst in that.”

Queried about the mainstream Japanese press’ toeing of the Olympus line on the Woodford story, playing it as an East-West showdown, Yamaguchi noted, “I never regarded this as a clash of cultures, but when I first started working on the story, I didn’t know about the hiding of losses that was underneath it. As I learned more about the accounting fraud that had occurred, I began to see it as a characteristically Japanese reaction — the notion of moving losses off the balance sheet to hide them was something we could regard as a cultural issue.”

Said Soble, “It’s important to remember that it was Olympus that initially framed it as a cultural clash in the announcement about Woodford’s firing. They didn’t say he was fired because he asked questions about some dodgy acquisitions; they said he was fired because he wasn’t fitting in. The Japanese media basically took that and ran with it.”

The director expanded, “Playing up Michael as a very aggressive guy who didn’t understand the culture was just total nonsense… This was just a cover story, and after Woodford went to the Financial Times and it was known around the world, I think that became very clear, even to the Japanese press. You see in the press conferences with the executives in the film, the Japanese press were asking very tough questions and turning pretty nasty, but the executives weren’t giving any answers. Seeing those interactions, it becomes obvious that this is a case where these guys… no one in their right mind would say the things they were saying in a public forum, when this is a listed company that has access to public funds. But I was in the court when [former Olympus Chair] Mr. Kikukawa testified, and he [was convinced] that the firing of Woodford had nothing to do with [the financial issues].”

Jonathan Soble scooped the scandal in the Financial Times. ©Koichi Mori

One longtime FCCJ member argued that tobashi, the deferring of losses, should not be considered cultural, since “it’s a normal accounting practice” on a worldwide basis. “After the bubble collapsed,” he said, “tobashi was taken for granted, because otherwise a lot of companies in Japan would have gone bankrupt... so what is the cultural dimension?”

The director recalled, “I asked the same question to Jonathan [Soble], because apparently, tobashi was a word used outside of Japan as well. I asked if there was something specifically Japanese about the concept, and his answer was that it was something that could be done in a similar way, on the books, in other countries.”

Added Soble, “The Japanese term caught on, but it doesn’t mean it’s a particularly Japanese thing. And it’s true, it was perfectly legal for the first decade or so after the bubble burst. If it hadn’t been, if companies had been forced to admit all their losses, you would have had all these companies, employing tens of thousands of people on paper, that would’ve been bankrupt. You would’ve had a whole lot of unnecessary economic and social disruption in Japan. So the government essentially allowed a long time for companies to defer losses, using various techniques to get them off their balance sheet, so it didn’t show up. Many companies, not just Olympus, did this. You had whole departments in respectable investment banks in Japan dedicated to helping them come up with methods to keep these losses off the books.”

©Koichi Mori

He continued, “But you can’t do that forever, and eventually the government said, ‘We’re going to tighten the rules.’ It went from perfectly legal to frowned upon to illegal but not enforced to ‘We have to stop this.’ Most companies took those 10 years to put their houses in order. Olympus failed to do that. It’s a bigger story than this, but these are the bones of the story.”

Said Yamaguchi, “I don’t want to stretch things out, but I would insist that the urge to hide the shame of having incurred losses is, to a certain extent, a characteristically Japanese trait. When we look into the cottage industry that’s taken shape here, an industry of experts who are prepared, for a fee, to help company’s hide losses, we find that a lot of the experts are non-Japanese. Olympus received a lot of assistance from a European investment bank. So to that extent, I would agree with you that this is not confined to Japan.”

Miller interjected, “I would like to argue that there was a tremendously cultural dimension to what happened at Olympus. At the end of the day, there was no magic. The balance sheet remained balanced… and you had three presidents in a row who would have been incredibly ashamed and embarrassed to have incurred such huge losses on ill-conceived financial speculation, but who were much less embarrassed or ashamed to have recorded grossly inflated goodwill in connection with stupid acquisitions. This is something that would never have occurred in America, because these transgressions are equally silly. Only in Japan would you look at one as being more grievous than the other. It’s very much a cultural problem.”

Soble agreed. “The idea that you can get away with that rests on the idea that your shareholders will never come down hard on you for overpaying for an acquisition. This is probably more true in Japan than in other countries. There’s an economic argument for not bankrupting companies, but these guys weren’t motivated by big economic calculus, they were motivated by the internal pressure to make sure that [a former] president isn’t embarrassed because of decisions he took. Those motivations are probably stronger in Japan.”

Articles by independent journalist Yoshimasa Yamaguchi first prompted Woodford to

ask the financial questions that lead to his firing. ©Koichi Mori

Another longtime FCCJ member, referencing Nissan CEO Carlos Ghosn’s firing of Nissan employees, “using gaiatsu, or foreign pressure, to cover up the embarrassment,” asked what might have happened if Woodford had not decided to “air his company’s dirty laundry” in public. Explained Soble, “Initially, to the extent that Olympus wanted to use Michael as an outsider, even though he’d worked for the company for 20 years, it was on the operations side. Olympus had to restructure. And Michael, in Europe, was known as a cost-cutter, kind of like how Carlos Ghosn was known as a cost-cutter. So the idea was that you bring in the European and have him do things that, for social reasons, would be difficult for a Japanese CEO, to cut jobs and cut costs. The idea was to have him do that, but to keep the past losses out of sight. Which is a pretty risky decision.”

Miller clarified, “I want everyone to go home with an accurate understanding of Michael’s stance. Long before he became president of Olympus, I argued with him many times about the massive employment in Olympus’ camera operations, for example. I said, ‘Don’t you have to get rid of those people?’ And Michael always said, “No! You don’t cut jobs. My job is to save jobs and protect lives.’ He’d been saying this to me for the past 15 years. After he was named president, of course he looked for places to get rid of people who were making huge salaries for doing very little. But that was not the people who were generating value in the trenches. He was always dedicated to preserving those jobs.”

Samurai KM--9217

Waku Miller is a longtime friend and advisor of Woodfords's, and now his de facto

representative in Japan. ©Koichi Mori

Asked whether lax oversight by shareholders had been a major factor in the crisis, Soble said, “You can disguise a big loss on an investment you made 20 years ago as a foolish and massively overpaid acquisition you made yesterday only if you can be confident that your shareholders aren’t going to question you or punish you for it. That worked at Olympus until the press got hold of it and it all came out.”

But Yamaguchi noted, “I perceive some gradual changes for the better. Just today, I read a story about a metals processing firm that had moved to name a new president. One of their largest shareholders actually came out and objected, and blocked the proposed change. This would have been unheard of several years ago. Nomura Asset Management is moving a lot of money and becoming something of an activist shareholder too. These are small steps, but they’re significant.”

The director, asked why the documentary doesn’t present Olympus’ side of the story, responded, “We approached their lawyers, but access was denied. We knew, going in, that it was going to be very difficult to have any access. My job as a filmmaker was to figure out how to present this in a somewhat comprehensive manner without having that perspective. Japanese investors and distributors pointed out that we don’t have a movie without that perspective, without new revelations, whether [former Olympus chair] Mr. Kikukawa’s testimony or other people involved. I felt it was worth telling without having that perspective, that there was so much we could present that was more relevant to what was going on and is still going on.”

Executive Producer Kazuyoshi Okuyama explains the documentary's genesis. ©Koichi Mori

Explaining why the Japanese release had been delayed, Yamamoto said, “We finished the film in 2015 and were looking for a distributor, but we knew not many would be willing to put it in theaters. Olympus are big advertisers in many major media outlets. It took a long time, but Uzumasa stepped in with an offer and that was really a lucky break for us. I made this especially for the Japanese audience, and I’m happy we’ve been given this opportunity.”

In the night’s most unexpected line of questioning, a film historian in the audience asked about the involvement of Kazuyoshi Okuyama, one of the film’s executive producers. Okuyama, he said, “had his own unceremonious removal from his company, Shochiku, and [I’m wondering if] perhaps he felt something sympathetic with Mr. Woodford.”

To his surprise, Okuyama was in the audience and willingly took the microphone: “Absolutely,” he concurred. “When I read Michael’s book, I saw compelling parallels between his experience and mine. [But] the most compelling aspect for me was the story’s universal message, a message about the struggle between the organization and the individual; the inevitable conflicts that arise between them in any society. That’s what grabbed me about the story, originally, the common ground between what happened at Olympus and what happened at Shochiku.”

The finished documentary refrains from mentioning Shochiku, the kabuki and film production behemoth. But as Yamamoto put it, “I think we shared the mutual goal of telling a universal story with universal themes. And I think that’s what we’ve done.”

©Team Okuyama / Uzumasa

Posted by Karen Severns, Tuesday, April 10, 2018

Read more

Published in: April

Tag: Olympus scandal, Michael Woodford, corporate governance, tobashi, profitpadding, whistleblower, culture clash, documentary

Comments