The day after Tezuka’s Barbara received the Golden Bat for Best Film at the 40th Fantafestival in Rome, Macoto Tezka appeared at FCCJ to discuss his prizewinning work.

“This is the first award given to the film, and I’m really happy that it comes from a fantastic film festival,” he told the audience following a sneak preview screening. “It has a lot of fantastical elements in it, so it brings me great joy that it’s been so wonderfully received by film enthusiasts who have an eye for such films.”

The Fantafestival jury had cited Tezuka’s Barbara for its “representation of an outside-the-box love story” and for “transcending the supernatural genre with great visual impact, in which the refined photography of the master, Christopher Doyle, excels.”

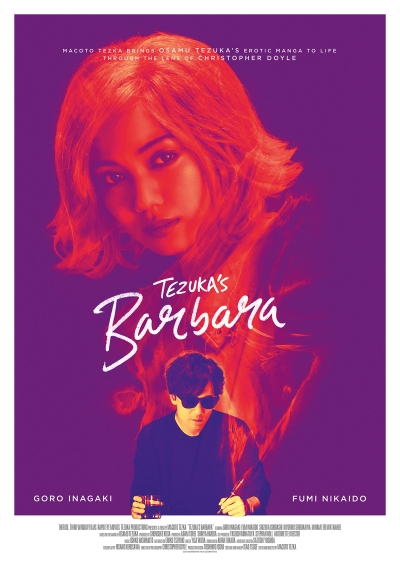

Barbara (Fumi Nikaido) and her latest rescue, Mikura (Goro Inagaki). ©2019 Barbara Film Committee

Admitted Tezka, “I have an affinity for Italy. I received an award for Hakuchi: The Innocent at the Venice Film Festival (in 1999), and have received many invitations from other Italian festivals since then. It’s also an honor for me because Italy has given us so many great filmmakers and such influential aesthetics. I’m overjoyed that my film’s aesthetics and beauty have been recognized.”

Tezuka’s Barbara is the second film he has based on an original manga by his father, Japanese comics godfather Osamu Tezuka (Astro Boy, Kimba the White Lion), but the first live-action adaptation. Planned in celebration of what would have been Tezuka’s 90th birthday, with support from producers in Japan, Germany and the UK, it refocuses the manga’s increasingly transgressive story on the love affair at its core, captured by Doyle (In the Mood for Love, They Say Nothing Stays the Same) in swooning retro-glam images, and driven by a jazzy soundtrack from frequent Tezka collaborator Ichiko Hashimoto.

Mikura and a figment of his wayward imagination. ©2019 Barbara Film Committee

The elder Tezuka had serialized “Barbara,” a dark and sexually-charged tale about a famous author’s gradual descent into debauchery and eventual madness, from 1973-74. Loosely inspired by Offenbach’s The Tales of Hoffman, it was not only a satire on Japan’s literary and political establishments, but also a supernaturally-tinged exploration of the power of the authorial voice.

Like the manga, Tezuka’s Barbara follows writer Yosuke Mikura (played by former SMAP superstar Goro Inagaki), who is at the pinnacle of success but whose crippling sexual perversions have rendered him creatively bankrupt. One night, he finds a young woman lying in a drunken stupor and, after she’s quoted French poetry to him, takes her home. Barbara (Fumi Nikaido) remains drunken and obnoxious, but her presence jolts him out of writer’s block and away from self-absorption. Once their relationship is consummated, however, harm begins to come to Mikura’s closest friends and his suspicion that she is a muse seems to be confirmed. And then she disappears.

Mikura with his muse. ©2019 Barbara Film Committee

Why, Macoto Tezka was asked by one audience member, did he decide to update the story to the modern day? “Although it was written in the early 1970s, I had no intention of actually setting the story in the 70s,” he explained. “I felt it had a universal thread and wanted to place it in an unspecified time. The retro feeling of the manga is an important ingredient in the original, so I wanted to [maintain that]. What you see on the screen is contemporary Tokyo, but we’ve added the flavor of taking you back in time. The use of jazz music, which was prominent in the 1950s-60s, is an additional nuance that gives it a sense of déjà vu.”

Prodded for particulars about the autobiographical nature of the work, Tezka said, “We always hear that while he was writing this, my father was living through hard times as a [creator]. But of course, needless to say, artists always have a conflict in our hearts — that’s what it is to be a writer or an artist.

©FCCJ

“The fact that the protagonist is a novelist comes naturally to me, since I was raised in that kind of environment, with people in that line of work very close to me. I think it was the same with my father — I don’t think he was trying to divulge his private life through his work. I think the profession of novelist is used as a metaphor. The conflict that we see is that of an artist who is bound by logic and words, but is also very aware of this world that is beyond logic or language.

“In psychology, this would be characterized as logos vs. eros. What you see in the film is a merging of the two. I took it as a challenge to include things that could be explained logically as well as to infuse the film with things that go beyond those boundaries.”

Tezka was asked “how faithful or how rebellious” he’d been with his father’s work. “I’ve read the manga tens of times, so it’s [part of me]. However, I didn’t want to be too attached to the original. There are many fantastical elements in the manga, and those are the ones I especially liked and wanted to include in the film. They were the scenes that were really joyful to make.

One of the film's many fantastical scenes, with an unforgettable Eri Watanabe. ©2019 Barbara Film Committee

“The cast and crew were also fans of the manga, so that allowed me to not be too stubborn about my own vision for the film, since they had their own ideas about the work. I was like a spectator on set, watching how the actors created their characters and how the crew created the scenes. It was all very interesting, and all I had to do was bring all the elements together.”

As for working with screenwriter Hisako Kurosawa, “What I told her was that, although the manga comprises many themes and many characters, I wanted to trim it down to just the two main characters and not include any superfluous characters. Since the manga was written by a man and I’m also male, I wanted a female perspective. So I left her with a lot of freedom in writing the screenplay.”

©FCCJ

One audience member, noting that Tezuka’s Barbara feels very international despite being so specifically Japanese, asked how the director had melded the two approaches. “Although the backdrop [of my father’s manga] is Japan,” Tezka responded, “it has a universality, an internationality to it. I had offers to develop it overseas, to create a film that was set elsewhere, including changing the setting to Prague. But I was more interested in setting it in Shinjuku, because I thought I would be able to shed light on aspects of the area that even the Japanese are unaware of.

“There are quintessentially Japanese facets to the story as well as to the behavior of the characters, and whatever I made was going to be quintessentially Japanese. But we used a [non-Japanese] cinematographer because I wanted to capture the wonderful, interesting aspects of Japan that we haven’t noticed.”

©Koichi Mori

With its story inspired by The Tales of Hoffman, and its references to the work of Nietzsche and Verlaine, a film historian asked, “Is it possible to make such a film in today’s Japan, given your strong artistic vision, without the support of German and UK distributors like Rapid Eye Movies and Third Window Films?

“I’m someone who thinks that even in Japanese filmmaking, we should be employing more international talent,” responded Tezka, “because in terms of mindset, technique and technology, things have gotten quite insular. Filmmakers have become complacent and smug. I think cinema is a very international thing, and it’s important to include diversity. When we look back at Japanese cultural history, we’ve always brought in and adopted various international elements.

“I think the support [of foreign distributors] in bringing Japanese [films] to an international audience, and to spreading awareness of what we do, is essential. In all my future work, I intend to continue teaming up with international talent to make Japanese films.”

Inevitably, Tezka was asked about the impact of Covid-19: “Considering the current situation, do you think the film takes on any new significance?”

Tezka with his Italian award and the gorgeous Japanese poster. ©FCCJ

He replied: “When I first considered adapting my father’s work, I saw the film as focusing on connections or relations, either between people or between people and the city. The prominent theme I wanted to depict was eroticism. It’s about two human beings coming together physically, through the flesh, rather than through words or logic.

“As the world tries to weather this pandemic, we see a rupture in human relations because we’re not allowed to touch each other. That makes this sense of human connection even more valuable. Because we’re living in a digital age, where people are increasingly communicating through digital networks, I wanted the film to depict a quiet, subtle resistance to where the world is headed.”

©2019 Barbara Film Committee

Posted by Karen Severns, Thursday, November 19, 2020

Selected Media Exposure

- 映画『ばるぼら』手塚眞監督が日本外国特派員協会で会見

- 『ばるぼら』会見に手塚監督、伊で受賞発表

- 手塚眞監督登壇『ばるぼら』日本外国特派員協会上映会・Q&A

- 手塚治虫禁断の問題作を実写化した映画『ばるぼら』、手塚眞監督が上映会Q&Aに登壇!

- イタリア「ファンタ・フェスティバル」最優秀作品賞受賞に手塚眞監督「大変嬉しい」―『ばるぼら』上映会Q&A

- 先日イタリア・ローマで開催されたファンタスティック映画祭。 なんと『ばるぼら』が最優秀作品賞を受賞!

Read more

Published in: November

Tag: Osamu Tezuka, Macoto Tezka, Christopher Doyle, Fumi Nikaido, Goro Inagaki, manga adaptation, awardwinning

Comments