Koki Fukyama’s Children of Iron is that rare thing in Japan: a bittersweet coming-of-age drama that is powerful yet completely unsentimental, deceptively simple and infused with both humor and pathos. FCCJ’s audience immediately recognized its deeper import, however, and during the Q&A session following the screening, attempted to probe the director for his thoughts on the convulsive changes currently redefining the dynamics of Japanese families. But Fukuyama demonstrated the same restraint and reliance on brevity that his film (only 74 minutes long!) champions.

He was surprisingly open, however, about the source of the story, which is set against a backdrop of single parenting, midlife remarriage, domestic violence, school bullying and economic hardship in a blue-collar suburb north of Tokyo. It is Fukuyama’s own boyhood story, in fact, and it grew into a film only after his onetime stepsister found him online, some 35 years after they’d been separated. The grown-up Mariko recalled their childhood quite differently than he did — “In certain cases where I’d remembered helping her out, she said, No, she was helping me out. I realized that guys tend to cast themselves in a heroic role in our memories” — but Fukuyama took the rough outlines of their shared past and worked with a professional scriptwriter to polish it into Children of Iron.

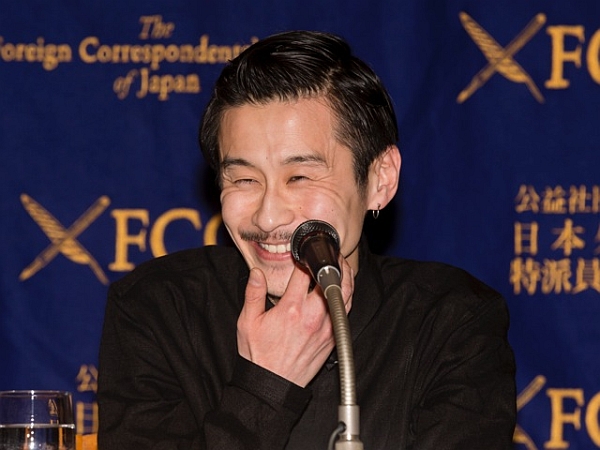

Fukuyama's own childhood inspired the story, which he decided to "soften," since the

reality was so harsh, and he didn't want to create a polemic. ©Mance Thompson (left)

After winning acclaim for his short films and his first feature, Fukuyama was selected by the Skip City International D-Cinema Festival to receive funds for production of his second feature, with the stipulation that it take place in the festival’s home, Kawaguchi City. Children of Iron then became the opening film for the Skip City Festival in 2015.

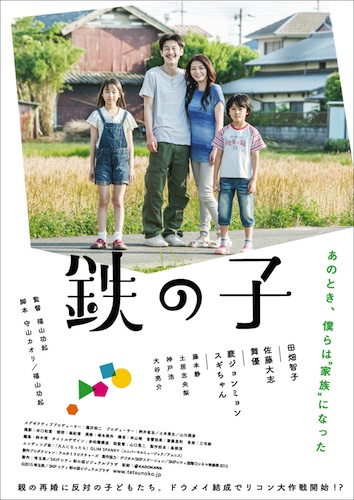

The two protagonists of the film, Mariko (Mau) and her new stepbrother Rikutaro (Taishi Sato), are living near the iron mills of Kawaguchi, made famous in their heyday by the 1962 film Foundry Town (Kyupora no Aru Machi), starring Sayuri Yoshinaga, but now even less prosperous. Mariko’s unemployed father (Jyonmyon Pe) and Rikutaro’s bar-hostess mother (Tomoko Tabata) have just married, and the kids must now share both a room at home, as well as the same class at school. When their classmates bully them — “siblings the same age are weird!” — Mariko enlists Rikutaro’s support in a “Divorce Alliance” to force their parents apart. The alliance is draconian, with rule breakers to receive the death penalty.

The two set about sabotaging the new marriage: ruining mom’s curry while she’s at work, scaring dad into thinking the house is haunted, smearing lipstick on his collar… but their plots seem to produce the opposite effect. And before they realize it, Mariko and Rikutaro have become friends. Yet as suddenly as they’ve come together, the family begins to fall apart… and a lump of polished iron and a tube of lipstick assume talismanic import.

Metropolis film critic Rob Schwartz probes the director

for details about the Rashomon-esque process of recalling the past.

Children of Iron depicts its struggling modern family mostly from the children’s point of view, finding an endearing balance between their often-grim reality and the magical coping mechanisms that comprise the process of growing up. Most of us had a favorite spot in childhood, a place we could go whenever we felt anxious or fearful. But few of us had a spot like Mariko’s — a magical tunnel to different lands, where she can make a wish and emerge at the other end in Candy Land or No Homework Land or No Mushrooms Land or even We Can Fly Land. When she allows Rikutaro to visit the tunnel with her, it is one of the film’s most enchanting, yet haunting, scenes.

“To me,” Fukuyama admitted during the Q&A session following the screening, “family is a very complicated thing. There is love, but there ’s also hate. There’s both good and bad. Situations can be very harsh. But I didn’t want to vilify either of the parents, because I think the father and mother were doing their best. So I think this is a story about trying to survive and do one’s best in situations that you really can’t do anything about. That goes not only for the children, but the parents as well.”

Pe's biggest struggle? That curry with carrots. ©Mance Thompson

From his hints about a father who was far more neglectful and abusive than the character onscreen, Fukuyama’s choice of actor Jyonmyon Pe is unexpected. A mainstay in many of the rough-and-tumble films of Sion Sono and other genre hits, as well as a regular on TV and stage, Pe is neither physically imposing nor particularly paternal-seeming. But he turns the father’s childishness into a malevolent force. “ Because it was my first role playing a father,” Pe told FCCJ’s audience, “I was really nervous going into the project. I didn’t have that many conversations with the director, but I made some suggestions that he incorporated into the shooting process. I can’t say much about my approach to the character, but I can tell you about [my biggest challenge]. We were rehearsing the curry scene, and I discovered there were carrots in the curry. I hate carrots! But I didn’t want to let the child actors know that, even though we were doing one take after another.”

©Mance Thompson

Fukuyama added that Pe had been cast after read-throughs of an early script draft, which contained several scenes between the children and the father that had to be cut when the filming period was reduced to just eight days. “Since he knew more about the relationships from reading that script,” said the director, “it was really easy to direct him, because I didn’t have to explain so much.”

Japan is only beginning to confront many of the social issues that are depicted in Children of Iron, so although Fukuyama’s experiences took place decades ago, they feel completely of the moment. Unlike most local films about fissures in the family structure, in which divisions are inevitably resolved in a happy ending, this one doesn’t soft-pedal the future. It’s a welcome addition to the genre, and should be widely seen.

— Photos by Mance Thompson and FCCJ.

©2015 Skip City D-Cinema Festival

Posted by Karen Severns, Wednesday, February 10, 2016

Media Coverage

- Children of Iron / 鉄の子

- ‘Tetsu no ko’: Aleación de recuerdos

- 『鉄の子』外国特派員協会試写、福山監督ら

- 「スギちゃんのシーンが一番良かった」にペ・ジョンミョン苦笑い

Read more

Published in: February

Tag: Koki Fukuyama, Jyonmyon Pe, Kawaguchi, Skip City International DCinema Festival, midlife remarriage, bullying, domestic abuse

Comments