Sometimes it just doesn’t matter that FCCJ’s seats aren’t well-padded or that unimpeded views of the screen are limited. Sometimes, all that mattersis having the privilege to watch a film by one of our greatest cinematic visionaries.

And this was one of those times.

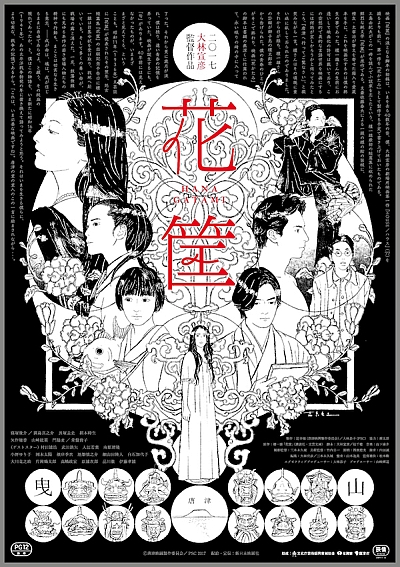

A surprisingly large audience arrived for the screening of Hanagatami from the early hour of 6pm; and when the lights came up 169 minutes later, they stayed glued to their seats for a Q&A session that went on nearly another hour.

The new masterwork by 79-year-old writer-director Nobuhiko Obayashi realizes his 40-year dream to bring Naoki Prizewinner Kazuo Dan’s 1937 novella to life, and it’s no exaggeration to view it as the culmination of his many impulses and obsessions, his magnum opus. A visual, aural and metaphorical feast, Hanagatami is also marked by an unbridled joie de vivre that borders on the contagious.

Producer Kyoko Obayashi has been her husand's filmmaking partner for 60 years. ©Koichi Mori

Those familiar with Obayashi’s work — he is the author of 2,000+ singular creations — may have been primed for the film’s staggeringly inventive visuals, its narrative density, its kinetic editing, elaborate soundtrack and fist-bumping creative energy. But as everyone in Japan now knows, the director learned he had stage-four lung cancer just before going into production on Hanagatami, and was told he had only 6 months to live.

That he finished the film is remarkable enough. That he underwent chemotherapy while shooting in 40 locations, with a huge cast of up-and-coming actors, is inconceivable. Yet Obayashi seems to have been cured by the very process of self-expression. Hanagatami fairly explodes with youthful vigor.

That vigor may no longer emanate as confidently as it once did from the director himself. Yet, as FCCJ’s crowd discovered when he took gingerly to the stage with his wife and producer, Kyoko, his physical diminishment has not affected his eloquence nor quenched his passion for his vocation. Obayashi is still a master storyteller, both on screen and in life; and the Q&A session, although too brief even at 50 minutes, did not disappoint.

The legendary creator of House, the 1977 comedy-horror extravaganza that brought him to overnight global renown when it was discovered in the West some 32 years after its release, the filmmaker has been exceedingly prolific in the third act of his career. Not only has he received critical acclaim for recent work like Casting Blossoms to the Sky (2012) and Seven Weeks (2014) — which together with Hanagatami form an antiwar trilogy of sorts — he has traveled the globe to be feted with career retrospectives and a handful of awards.

The main characters assemble in Hanagatami. ©karatsu film partners/PSC 2017

He has also become increasingly vocal about the role of filmmakers as messengers of peace, believing that their work must convey the urgency of today’s political situation in Japan. The first Q&A question addressed that role, when an American film historian asked, “Why did you choose such a fantastical, rather than a realistic, style to present the tragedy of war?”

“I chose a stylized approach because I didn’t think it would help cinematically to depict the subject realistically,” Obayashi answered. “My wife Kyoko sat beside me during the editing, and kept saying it didn’t matter how many incendiary bombs we had going off in a certain scene, the reality was 5 or 10 times worse. Even with the CG technology we have available today, it’s just not possible to depict reality with realism. I thought it would be more effective to use the construct and the deceit of fiction to convey reality. So I chose a heightened approach — heightened beauty, heightened reality, heightened acting, heightened directing — to get at what is really real.”

He then emphasized: “The lie that is most prevalent among us is the lie of peace. No matter how much we hope for it, we can’t attain it. This isn’t exactly an antiwar film; I just hate war, and I think that sentiment is conveyed.”

©Koichi Mori (left), ©Mance Thompson (right)

Obayashi had first planned to make Hanagatami in 1975, when he was enjoying a successful career directing commercials and short films. But history intervened with an invitation from Toho to help them reach a younger demographic with a new style of film that eschewed logic. (The resulting work, House, marked his feature debut.) Why then, asked a journalist, did it take 4 decades to finally make Hanagatami?

“Akira Kurosawa would often say that he had 30 films he wanted to make,” recalled Obayashi of the great auteur, “but that the proper timing would be decided by [the winds]. Hearing that, I realized that even if you have an important message to convey, there’s no point in trying to convey it unless there are ears willing to heed it. The purpose of [filmmaking] is to create a dialogue with the audience, and if they’re not willing to listen, there ’s no point.

“The author of the original novella, Kazuo Dan, did not have the liberty to say that he hated war and hoped for peace, because that would have instantly made him an enemy of the state in those days. Yukio Mishima [who was inspired by Hanagatami to become a writer himself] said that the only thing that matters during wartime is to love as if your life depends on it, or else to be a delinquent. The novella depicts characters who are loving as if their lives depend on it, and a close comradery between the male characters, who drink and smoke together. They even ride horseback together naked. But they end up wanting to kill each other. And these motifs were really the only way you could depict the horrors and atrocities of war.

High-school hijinx with, from l., Kubozuka, Emoto, Mitsushima and Nagatsuka. ©karatsu film partners/PSC 2017

“Now that times have changed, we have a younger generation that doesn’t know much about war, but they can hear its footsteps gradually approaching, and they’re finally beginning to open their ears to what we have to say. We’re living in dangerous times. I felt that [Dan’s and] my father’s generation was telling me, ‘Now is the time. You have to make this film.’”

Hanagatami is set in the spring of 1941, and opens with 17-year-old Toshihiko Sakakiyama (Shunsuke Kubozuka), who has just returned from Amsterdam to Karatsu. Lonely in his high school dorm, he often visits his Aunt Keiko (Takako Tokiwa) and her young sister-in-law, Mina (Honoka Yahagi), who is suffering from tuberculosis. Mina’s brother also had TB, which emboldened him to march off to war. At school, where the teacher has them reading Poe’s The Black Cat out loud in English, Toshihiko meets a number of eccentric fellow students, including the “brave as a lion” Ukai (Shinnosuke Mitsushima), who goes swimming every dawn and enjoys being shirtless; the “zen monk” Kira (Keishi Nagatsuka), who walks with a cane, grew up as a Christian and utters cynical proclamations; and eager-to-please class clown Aso (Tokio Emoto). There are also the girls, friends of Mina’s: Akine (Hirona Yamazaki), whose family runs the town’s best izakaya and provides endless delicacies to Keiko’s household; and the mysterious Chitose (Mugi Kadowaki), Kira’s cousin, whom he has taught to use a camera.

As Japan marches inexorably toward war, these carefree youths gather for parties and picnics (and never seem to lack for the very best in creature comforts, including imported delicacies). But the boys know that all too soon, they will be sucked into the chaos of battle, try as they may to resist their destiny. One of the characters even references Sadao Yamanaka’s Humanity and Paper Balloons, the last film the director made before being sent to Manchuria, where he died. Finally, the friends gather one last time to attend the Karatsu Okunchi festival with its enormous floats, just outside the old castle...

From left, Yamazaki, Yahagi and Kadowaki. ©karatsu film partners/PSC 2017

In Obayashi’s bucolic fever dream, the Karatsu moon is always full, cherry blossoms bloom and fireflies flit, colors are eye-popping, poetry is on every lip, music ebbs and swells, mirrors crack, ghosts return with messages, and metaphors are hard to parse (like the falling crimson rose petal that transforms into blood as it hits a tabletop, a recurring image that is perhaps a memento mori for the generation destroyed by WWII, its souls lost and its survivors forever scarred).

But if Hanagatami is a cautionary tale for the Japanese who haven’t experienced war or hard times, as the director claims, it also touches on the familiar Obayashi lament over the loss of communities and traditions, local customs and cultures.

He discussed his approach: “When I became a filmmaker, I decided not to join a company and be a professional, but to live my life, with my wife as my producer, as an ‘amateur’ filmmaker. As an amateur, you have the freedom to do only what you believe in. Moviemaking is a business, and your freedom is [often] hindered. Filmmakers like Ozu and Kurosawa had limitations — maybe Ozu wanted to make a film like Ikiru; maybe Kurosawa wanted to make Tokyo Story. But it wasn’t possible for them, because they were commercial filmmakers. So I decided to become a freelance director, or honestly speaking, to be often unemployed.

“Kurosawa and Ozu had their own styles and themes. Kurosawa made films about society for Toho, Ozu made family films for Shochiku, Mizoguchi made period films for Daiei. [As a freelancer] I had to find my own path, and starting out with 8mm film, I decided I should become a furusato (hometown) director, and make films set in my hometown, Onomichi. Japan’s lush greenery and landscape were destroyed after the war, because we were such a hurry to revitalize our economy that all the scenery was ruined. What better thing to do than to make ‘home movies’ about the old ways of life and culture?”

To a question about Hanagatami’s length, Obayashi replied, “I don’t want to be bound by the rules of economics, because I think there can be 1- second films, 100-second films and films that could take a lifetime to watch. Film emerged from technological inventions, and I think I’m free to be an inventor myself, to try out possibilities and come up with new expressions that people haven’t seen before.”

Asked why he set the film in Karatsu, a small castle town in Saga, Kyushu, Obayashi explained, “Dan mentioned that the story could be set in a fictional town, not a specific one. So I asked him, when we were thinking of shooting the film [in 1975], where it should be set and where we should location hunt. He said, very seriously, ‘Go to Karatsu.’ At that time, he had been told that he had stage-four lung cancer, so I took this to be akin to a final request. I went with his son, Taro, to Karatsu, and was very impressed with it. [Forty years later] we shot every scene in Karatsu, although we couldn’t depict the landscape of the original novella. We depicted its spirit, and the spirit of Dan. But [the festival] was my wife’s idea.”

“We had looked at Nagasaki first,” said Kyoko Obayashi, but the reason I was really impressed with Karatsu was the Okunchi Festival, with all the floats. I discovered that only men, not women, are allowed to participate. I usually just go with my instincts, and intuitively, I thought that the spirit of this festival — the spirit of the floats and the men who pull them — would go well with Hanagatami. So I suggested that to my husband.”

Obayashi (in sunglasses) is surrounded by the Hanagatami cast after a screening of the film

at the Tokyo International Film Festival in October. ©Mance Thompson

“My wife’s instincts are really wonderful,” said Obayashi. “She manages to get to the truth, to the essence of things, so I usually go with her instincts. That allows me to find the right approach to directing the scenes. The spirit of the festival arises from some historical facts. Karatsu is a castle town, and even now, you can see a separation: those who lived within the castle walls were of the samurai class, and those outside were the merchants or commoners who worked for the samurai. The festival is very much a commoners’ festival, and those who participated were risking their lives.* When they were drafted into war, they would [go AWOL to] return to their hometown to participate, which was also risking their lives.”

[*According to sources online, the 400-year-old autumn festival, designated an Important Intangible Folk Cultural Property, features 14 massive floats called hikiyama, with the largest ones standing 6.8 meters tall and weighing 3 tons. They are designed to look like lions, grampuses, samurai helmets, sea bream, and flying dragons called hiryo, and are lacquered and finished with gold and silver leaf. The potential danger for participants can easily be seen in clips on YouTube.]

©Mance Thompson

Obayashi continued, “The festival site is the same location as warlord Hideyoshi Toyotomi’s base of operations, from which he would send troops into the Korean Peninsula. In this area of powerful samurai, the festival was all about the common people, a way for them to show their local pride to those in power. I also discovered that Kazuo Dan had committed a crime and been labeled a Communist when he was 18 years old. He spent time in Karatsu, so going there and shooting felt like I was coming full circle, and truly making a furusato film about the spirit of these townspeople.”

“If war is worth fighting for,” goes one line in Hanagatami, “so is a festival.” And no one puts on a festival like Obayashi. May his next film — yes, he has announced plans to go into production soon — be as brilliantly idiosyncratic and inspiring.

©karatsu film partners/PSC 2017

Posted by Karen Severns, Tuesday, December 05, 2017

Selected Press Coverage

- 大林宣彦、「反戦映画を作っているわけじゃない」外国人記者に戦争観

- 大林宣彦、最新作「花筐」に託した希望語る「平和という“嘘”が本物に」

- 大林宣彦が『花筐/HANAGATAMI』に注いだ、語りつくせぬ“映画”と“平和”への情熱

Read more

Published in: December

Tag: Nobuhiko Obayashi, Kyoko Obayashi, Akira Kurosawa, antiwar, WWII, Kazuo Dan

Comments