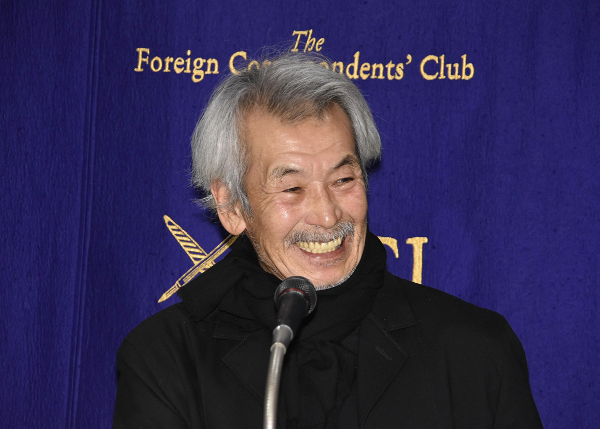

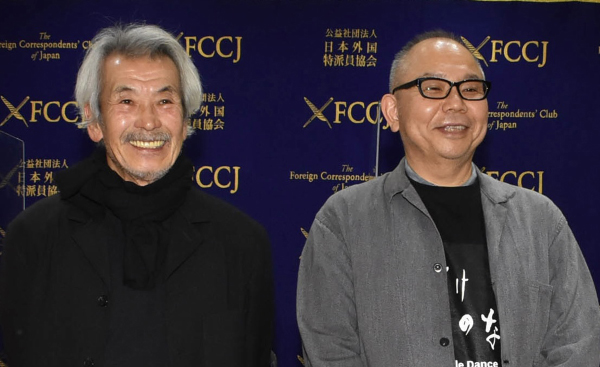

Internationally acclaimed dancer, award-winning actor and devoted farmer Min Tanaka responded so enthusiastically to questions from the FCCJ audience during the post-screening Q&A session following The Unnameable Dance (Nazuke-yo no nai Odori), that he extended the session to a full hour.

As he was descending the dais for the photocall afterward, he told the moderator, “Everyone was so alive, so engaged — it was just beautiful. I felt like I was in another country.” One imagines that Tanaka is in the habit of spontaneous generosity.

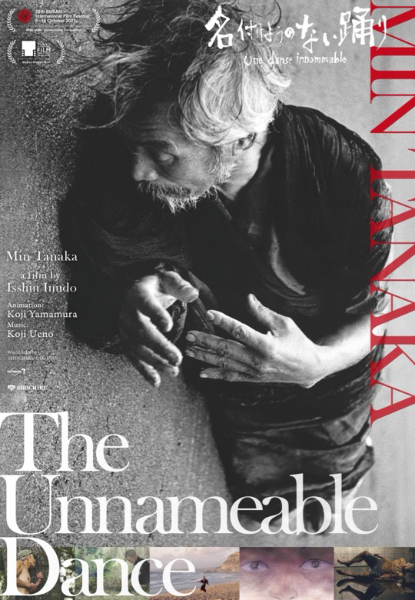

His life and work, with further examples of bigheartedness, are the subject of Isshin Inudo’s luminous documentary, which follows its 75-year-old star for nearly three years as he performs in multiple locations at home and abroad, tends to his organic farm in the mountains of Nagano, and reminisces about a challenging childhood. The film celebrates the artist’s sublime craftsmanship, as well as his restless spirit.

"Now that we've been through this process," said Tanaka,

"I think of Mr. Inudo as a comrade in dance." ©FCCJ

A predominately solo performer for over five decades, since 1966, Tanaka’s singular “unnameable dance” evolved from the inspiration he draws from his immediate surroundings, and belongs to no school or style. In the film, his site-specific, genre-bending, improvisational pieces take place against the backdrop of everyday life in locations both beautiful and prosaic, from Santa Cruz, Portugal to Ehime, Japan.

Inudo, a director known internationally for such films as Josée, the Tiger and the Fish (2003) and La Maison de Himiko (2005) — which marked his first collaboration with Tanaka — combines dance performances. vital archival footage and snippets of Tanaka’s films with evocative animation by Annecy Award-winning, Academy Award-nominated Koji Yamamura. Used primarily to illustrate Tanaka’s recollections of growing up during WWII and finding his own feet in contemporary dance, Yamamura’s vibrant vignettes allegorize the dancer’s effervescent inner spirit (“my kid”) and in one spectacular instance, interact with Tanaka himself.

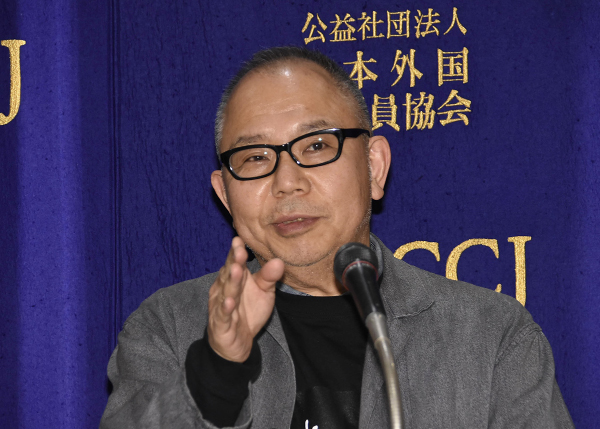

Inudo told the audience, “From the time I was a little boy, I’ve been watching all the

grownups speaking here at FCCJ. So I'm very, very happy to be invited tonight.

My mother is thankfully still alive, so I look forward to telling her about it later.” ©Koichi Mori

Asked about the inception of the project, Tanaka explained, “It all began when I was in Prague and a festival director from Portugal visited me, wondering if I would like to dance for his festival. I had danced and performed in various countries, but not yet Portugal, so I thought, why not go there? I talked with Mr. Inudo, whom I already had a longstanding friendship with, and asked if he would like to tag along.”

The director, who recalled admiring “scenes of Portugal in films by Wim Wenders” and had been wanting to visit the country himself, agreed. Then, “I began to think that if I was going to be traveling to Portugal with Mr. Tanaka, it would be a real waste not to capture his performances. So I brought along two cinematographers that I’d worked with before, as well as my wife” (Minori Inudo became one of the producers of The Unnameable Dance).

Tanaka in Portugal, following a street performance. ©2021 THE UNNAMABLE DANCE FILM COMMITTEE

“After shooting eight performances, “we brought the footage back to Tokyo and edited it into a 15-minute short. We took a look and thought it was quite a good dance film. At that point, I started to think about making a 2-hour feature.”

That film would go on to have its world premiere at the 2021 Busan International Film Festival and the 2021 Tokyo International Film Festival.

Here are further highlights of the Q&A:

Q: How did you go about making this film practically? It’s very much a collaboration between equals, which is different from Mr. Tanaka being an actor in Mr. Inudo’s film. As a dancer who mostly dances alone and moves very freely and spontaneously, how did you adapt that to a filmmaker and his crew when filmmaking is not a very spontaneous art form?

Tanaka: I was very doubtful whether it would even be possible to capture dance on film. I had to clarify that point, and we had to start from there, because I dance in a way that is succinct and complete in that moment. And that moment is not something I can recreate.

To just simply record that ephemeral creation, just that moment, it wouldn't be an exact recreation of what I had delivered to the people who are watching. I told Mr. Inudo, ‘If you’re going to capture my work, you are free to recreate it in any way you like. You’re free to cut it up and edit it any way you like. Capture my dance on film and make your own thing out of it.’ We came to an agreement on that point and it started from there.”

©Koichi Mori

Inudo: “I didn’t think through what kind of film I ultimately wanted this to be for the two years of shooting him [on the road]. I decided I would think about that afterwards. So we recorded 30 pieces during his travels. After that, I decided what kind of film I wanted it to be and wrote the script. Then, based on the script, I rearranged the sequences of the dances that we’d recorded during his travels. I wanted to deliver a sense of this temporal experience where an audience member leaves home, goes to [Tanaka’s] performance and then returns.

“What I was very careful about, and this is a very important point, was that I never conducted any interviews with Mr. Tanaka while we were recording his dances. I made it a point not to ask, ‘What is this dance that you're dancing right now?’ Or ‘What are you going to be dancing next?’ That was a conscious decision.”

Tanaka: “During those two years of shooting, my task was to just keep dancing. Not once did I try to recreate the same moment. So it was just me existing and living in front of the camera, and I think that’s one of the characteristics that sets this film apart. There is no ‘Lights, camera, action!’ There are no bloopers.”

Inudo: “We were careful about making sure we knew just what kind of place or atmosphere Mr. Tanaka would be dancing in beforehand, because it was all going to be improvisation. Therefore, we wouldn’t really know where or how to move, or how to capture him and from which angle. So we at least had to have the place firmly in mind beforehand. Of course this is what you do with [fiction] film sets as well. You create the place and you're very conscious of it before you shoot.”

©2021 THE UNNAMABLE DANCE FILM COMMITTEE

Q: The film is titled The Unnamable Dance, but there are so many spoken lines in it, and they're so wonderful and poetic. How was the narration created and edited? What kinds of discussions did you have with Mr. Tanaka?

Inudo: Mr. Tanaka is also a very good writer. He writes very clearly and meticulously. He writes columns for newspapers and has also written books. So I gathered prose that kind of stood out to me from what he had written, and indexed them into themes. I picked lines that especially resonated with me, and I rearranged them into the narration that you see in the film. So the words are his words.

Since Mr. Tanaka's dance style is very improvisational, you would think that it comes from a very primal and passionate place. But that’s not exactly the case. He really thinks in words about what he does, and he very meticulously verbalizes what his dances, his performances, are about or what they are. I thought it would only be a hindrance for me to project my own perception of his dance onto the film. This is why I used his words.

But I was very conscious about not asking him or interviewing him about the performances. We would have chats and make small talk. He would tell me stories about these figures that he’d collaborated with in the past, but not once did I try to interview in or ask about him about the essence of his own dance.

©Koichi Mori

Q: I was really fascinated by your choice of Koji Yamamura for the animation. Obviously, he's somebody who's able to express through animation what Mr. Tanaka is able to do with dance, things that may be difficult to express with words. But at the same time, he's able to interpret words through animation. Could you explain how you came to collaborate with him on this project and how that collaboration worked?

Inudo: Mr. Yamamura and I went to the same university and I've been friends with him for over 30 years.

There's a certain part in the film where Mr. Tanaka talks about his childhood imagination, and he calls it ‘my kid.’ I came up with this idea that this should be recreated in animation, this concept of ‘my kid.’ And we ultimately came to hire Mr. Yamamura.

As audience members, when we see Mr. Tanaka’s dance performances, it's not like we're all engrossed in his work or cheering him on. We’re not watching like, ‘Oh, how wonderful Mr. Tanaka is!’ It's more of a one-on-one conversation, a very personal conversation between one audience member and Mr. Tanaka as he dances. So I wanted to recreate that kind of sensation through Mr. Yamamura’s animation, just this sense of letting your imagination wander.

Yamamura's depiction of Tanaka as a youth. ©2021 THE UNNAMABLE DANCE FILM COMMITTEE

I also thought it would be a good idea to bring Mr. Yamamura and Mr. Tanaka together, because their attitudes toward work and their everyday lives is very similar. Mr. Yamamura also works alone as an animation artist. I mean, he's drawing every day, one sheet at a time. This is very much like the style of Mr. Tanaka, because he’s in the field every day doing his farm work, which creates this body that he uses for dance. So their art is a culmination of what they do every single day in their daily lives.

They're very similar in that respect, and I thought Mr. Yamamura would be one of the very few people who could collaborate with us on this project, being on equal footing and of the same caliber as Mr. Tanaka.

Q: I think there's a wonderful classical Japanese esthetic to Mr. Tanaka’s dance and the concept of space that was amazing to me. Do you think there's something classically Japanese about your aesthetic approach to dance?

Tanaka: Let me first explain that what we perceive as ‘Japanese’ was probably established between the 10th and the 17th or 18th centuries, and that is still the part of our lineage in terms of traditional Japanese culture. However, when the Meiji era arrived, I think we very hurriedly tried to adopt Western culture, the cultures of European countries and also North America. So I don't think there is any piece left of a quintessentially or purely ‘Japanese spatial sensibility’ or cultural perception in contemporary Japan. I don't think there are remnants of that anymore, in the purest sense.

But I think as a whole, we are perhaps headed toward a more modern sensation of a certain physicality or spatial sensation that may precede language or words. I think maybe as a species, we’re headed in that direction. In any culture, there’s the culture of language, the culture of word or scripture, and it’s very wide and diverse, indeed as diverse as the whole Earth.

I think that underneath it all, there’s a common language that we speak, and that’s the language of silence — something that eludes even words. After all, we are one species and we have these bodies. I think perhaps there’s a certain spatial sensibility that we all harbor inside of us, that we may not have realized yet. Maybe we can realize it, maybe we can acknowledge it. That’s my hope.

©2021 THE UNNAMABLE DANCE FILM COMMITTEE

Q: In the final scene, where Mr. Tanaka says something to the effect of, ‘I feel as if my brain or my head is sinking into the sea and I am very happy’ — Is that happiness [about] going into nothingness or, as we say in Japanese, mu?

Tanaka: First of all, I must say that I actually do not believe in mu. And I don’t have any desire to try to touch this sensation, because I want to be someone who's partying until the very last moment of my life.

I want to be able to use this body that I have to its fullest extent, so that I can connect with and communicate with the world. I want to fill my body with sensibilities and sensations up to the point where it nearly explodes, so that I can connect to and converse not only with the world, not only with other human beings, but also maybe even with bacteria.

That is really what my dance is all about. We are much more expansive than our bodies, but we are destined to be contained in our physical forms. I think that when I am dancing, it seems like I expand myself to the point where I almost feel like I can be dispersed into particles and just evaporate or travel beyond this physical form. But it's not very easy to verbalize the full performance in so many words after you dance.

Q: I have a question about the scene in which Mr. Tanaka is working with (collaborator) Rin Ishihara, and he tries to direct her using examples of what a raven does. I was wondering whether Mr. Tanaka has these images in his head while he's doing his own dance performances.

Tanaka: I need to talk about my relationship with Tatsumi Hijikata. The first time I saw him perform, it was a shocking experience for me. What he did was this type of dance that we now call Butoh, and everybody wanted to study under him. So they all went to study under him. I intentionally decided not to follow that trajectory because I wanted to discover my own form of dance.

Many years went by, and three years prior to his death, he came to see one of my performances. After that, I was able to enjoy a drink or two with him occasionally and enjoy talking with him. So I would say that I am not his protégé or student per se. I did not study under him, but any conversation with Mr. Hijikata inevitably led to what Butoh is about or what a Butoh dance performance is.

I think I was very, very fortunate to have this relationship with him. But what he did — and I have to be very clear about this — was a type of performance that comes from a word that is transferred to a bodily sensation that is transferred again into a very small movement, which crescendos again and again into a larger type of movement. This is what he taught me.

©FCCJ

So it's not about following a certain form of something or studying under the dancer or the performer. The performer has to feel the sensation within his or her own body, to be able to recreate that or to be able to deliver something. It's not delivering the truth just to copy the form or the movement. And this is what Mr. Hijikata was all about.

This is what I talked about with Ms. Ishihara [in that scene], going back to what Butoh is or what Mr. Hijikata was trying to do. I'm very heavily influenced by his work and by my conversations with him. But I am not a Butoh dancer, and I think Butoh is finished. Many people use the word Butoh to define a certain type of dance, or say that Butoh is a genre or subgenre of dance. This is completely wrong. It is a spiritual activity. Butoh performances are a spiritual activity and not a type of dance.

Q: What was the most thrilling discovery you made while directing this documentary, which is not your usual form?

Inudo: If there’s anything that I took home from this experience with Mr. Tanaka, it’s the sensation that when he talks, he's always talking about this space or this place that precedes words. With words we have our countries, we have our races and [languages]. But before that, there must have been a world that preceded words. The world where we were all as one. This was something that I’d never thought about until this experience with him. I can now say with a certain sense of conviction that, yes, there was perhaps a space or a place where there were no words and we were actually in this oneness. So for that, I have to thank him.

©2021 THE UNNAMABLE DANCE FILM COMMITTEE

Tanaka: When we were all starting to learn dance, all of our instructors, all of our teachers would say that dance is something that eludes words, that can’t be described in words. But that made me think, ‘Well, what is this technique that we’re all trying to learn, that we’re told is required if we’re going to be a dancer or to perform? Isn’t this half of that?’

We use our bodies to conjure these movements to the music we hear and to create these dance performances we do. But going back to this place that precedes words, I think that’s the place where the seeds of dance are. And if it’s all about technique or movement per se, it would be a dance stripped of its primal seeds. A dance stripped of its seeds is only half a dance. It’s only the branches and not the tree, not the trunk or the roots.

So I think it’s my job to replant the seeds of this form. I hope that we can use this film as a starting-off point to discuss this. And I want to continue discussing it for a very long time.

©FCCJ

©2021 THE UNNAMABLE DANCE FILM COMMITTEE

Selected TV Exposure

・news every. 2022年1月25日(火)15:50~19:00 日本テレビ