With his breakout hit 8,000 Miles (SR Saitama no Rapper) in 2009, writer-director Yu Irie struck pay dirt in his rural Saitama hometown, using it as the backdrop for a bittersweet tale about the struggles of wannabe rap stars. Returning twice over the next few years to complete a trilogy, he won a devoted international following for his humorous, humanistic depictions of the strivers, outsiders and has-beens who populated his particular pocket of the prefecture.

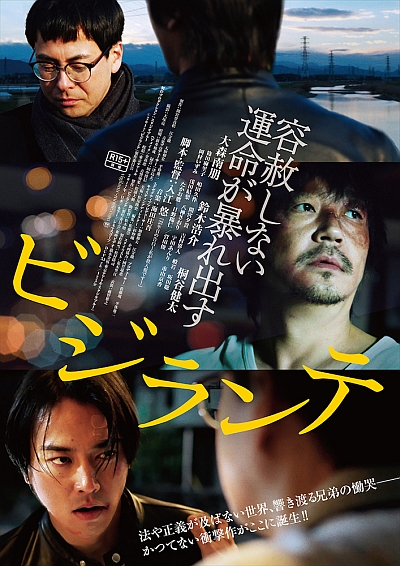

But with his new film, Vigilante, Irie makes it clear that home is decidedly not where his heart is. Penning his first original screenplay since completing the trilogy, the young hitmaker has once again revisited his roots — but this time, he has found them rotten.

The pitch-black world of Vigilante is one in which ethics have been torn asunder and the ugliness of humanity is on full display. Exploring such hot-button social issues as child abuse, drug addiction, sexual aggression, crimes against foreigners, crimes by foreigners, and the inexorable decline of Japan’s countryside, Irie’s unsettling vision allows nary a sliver of light to pierce the darkness.

The film begins with a chase through the twilight, as three small boys are pursued by a frightening adult figure. On the day their mother dies, the young brothers have attempted to kill their tyrannical father, Takeo (Shun Sugata), a leader in the local community. The eldest, Ichiro, runs away after the incident, and does not return until Takeo has died, 30 years later. In adulthood, middle brother Jiro (Kosuke Suzuki, TV’s “Dr. X”) has become a city council member, while the youngest, Saburo (Kenta Kiritani, Close-Knit), makes ends meet by managing a deriheru ("delivery health") call-girl business for a volatile gangster (rapper Hannya).

©Koichi Mori

After Takeo’s funeral, Ichiro (Nao Omori, Outrage Coda) suddenly reappears. He’s brought with him a notarized will, and declares that he will take possession of their father’s legacy. But Jiro needs to retain a large tract of nearby land for a megamall construction project that will ensure his political future. Ever the obedient civil servant, he must now choose between his family and his career prospects. As the brothers indulge in an increasingly violent tug-of-war, all hell breaks loose around them. A community of foreign workers clashes with an overzealous neighborhood watch group. Powerful politicians collude with organized criminals. Soon, tensions in the entire town begin to boil over.

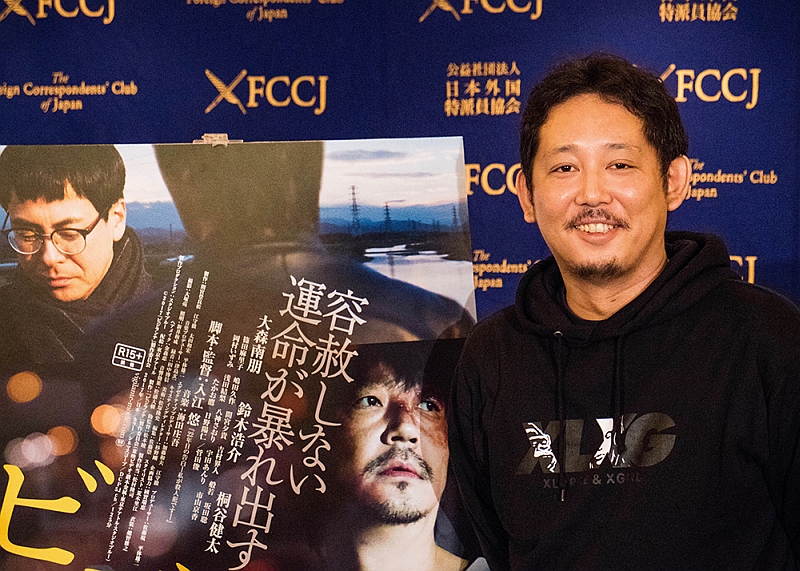

In the Q&A session following FCCJ's screening, Irie was asked whether any of the film’s political intrigues had been influenced by actual events in the director’s hometown. He responded, “I want to make clear that it wasn’t my intent to depict Fukuya — this is set in a fictional town. If I don’t make this clear, I’ll never be able to go back."

Kiritani confronts local gangsters in the film. © 2017 VIGILANTE Film Partners

Irie laughed before continuing, “I left Fukuya when I was 19 to study filmmaking in Tokyo, so I didn’t really have a full understanding of the politics of regional cities. What did leave an impression on me was that there were always yakuza at our local festivals. It was only after I started making films, and I would return home [on visits], that I started to realize there were these issues involving immigrants, these ‘trainees’ from overseas, and also that there were vested interests involved in public projects.”

Was it necessary to shoot in Fukaya, if audiences are not meant to connect the screen’s fictions with the real setting? Said Irie, “There was this impetus to go back, because the themes were personal. I could have shot elsewhere, but I wanted to return and get the support of people living there.”

Omori faces a bleak future. © 2017 VIGILANTE Film Partners

Vigilante was filmed in the dead of winter and mostly at night, which undeniably helped strip the performances by its three main stars of any artifice. But Irie admitted that he’s a bit worried the actors are still upset about the filming conditions: “A lot of my films are set in winter, actually. I suppose it’s a season I like a lot. When the three brothers were fighting in the river, it contributed to some movie magic. It started snowing while we were filming, and it rarely snows there.”

The film’s low-budget aesthetic reminded one critic in the audience that — long before Irie helmed big-studio productions like his Memoirs of a Murderer (which spent 3 weeks at the top of Japan’s box office earlier this year) — he had felt trapped in the no-budget rut. In 2010, Irie had gone on record with complaints that independent directors couldn’t have sustainable careers, and couldn’t possibly afford to live in a city like Tokyo. The voluble rant went viral, prompting a dialogue across the industry that continues today. Asked whether he felt any differently now, Irie admitted, “I’ve shot quite a few commercial films now, so I’m able to live in Tokyo. I made those comments when I [wasn't yet 30] to bring attention to the plight of young directors in the film industry, and I don’t think that situation has changed much at all. People forget about these issues all too easily.”

©Koichi Mori (left), ©FCCJ (right)

What does he think might be done about the situation? “Toei Video, which is behind Vigilante, is really unique,” he responded. “They back original scripts, rather than just those based on novels or manga, and this opens a lot of doors for people who want to work on original material, as well as for indie filmmakers. I think there’s a lot of work to be done to solve the problem, but when it comes to the major studios, I’d like to see more of them embarking on original projects. I think it’s up to my generation now to make changes by writing original scripts and finding producers, or it will never change.”

A leading critic in the audience, noting that Vigilante has echoes of Yoichi Sai’s Blood and Bones, another work that features an overpowering father figure, asked how important the theme of family ties is to Irie’s own work. “I wasn’t directly influenced by the film,” said Irie, “although I like it a lot. I think its depiction of a towering, violent father is unparalleled in Japanese film. As for my own work, I’d avoided depicting blood ties in the past; but two years ago, I was filming a jidaigeki film set in the Edo period, and I had to do some genealogical research. That led me to research my own family tree, and if you go back 5 or 6 generations, you reach the Edo period. I started thinking about blood ties and what family means, and that influenced this film.”

Suzuki (center) leads the neighborhood watch one fateful evening. © 2017 VIGILANTE Film Partners

He later admitted that he’d been “heavily influenced” by the star of Blood and Bones, “Beat” Takeshi Kitano, who also directs “starkly, painfully violent” films. “Kitano’s films really show us what it is to hurt another, what pain really is,” he explained. “That’s a theme that I wanted to revisit, What does it mean to hurt someone? What is pain? Vigilante doesn’t speak just about physical pain, but also emotional and psychological pain. I regret avoiding this theme until now. I’m interested in seeing how younger audiences will react — especially audiences that are used to watching bubbly coming-of-age films.”

Asked to explain the title, the director said, “I’ve had a long-time interest in neighborhood watch-type organizations, which are policing in an unofficial capacity. I’m personally quite scared of 'communities' and people who organize groups like that. What I wanted to depict was how the individual is swallowed up by the community, so the first title that came to mind was Vigilante.”

©Koichi Mori

He elaborated: “What I wanted to depict was not just person-to-person violence, but violence brought on by a certain economy or a community that swallows up the individual. I think it would be difficult for moviegoers to take home a positive message from the film. But I would like them to ponder the situation and imagine what they would do. I recently read a book by Mario Vargas Llosa in which he discusses the character of Emma Bovary, and he wrote, ‘Her death is our hope.’ He meant that such characters die for us, in our place, and we should derive a sense of relief. That really struck a bell with me, and I hope Vigilante’s viewers will feel the same.”

Although he will surely continue to write and direct entertaining stories about viral epidemics, bio-terror, serial murderers and spies (if his recent successes are any indication) the pared-down nastiness of Vigilante should reassure fans of Yu Irie that he does not intend to shy away from shocking visions, even in today’s shock-averse Japan.

© 2017 VIGILANTE Film Partners

Posted by Karen Severns, Friday, November 17, 2017

Selected Press Coverage

- Vigilante: Brotherly love takes a beating in an intense family drama

- 『ビジランテ』入江悠監督「キラキラした学園青春映画を観ている人に観てほしい」外国特派員協会記者会見レポート

- 外国特派員からも感嘆の声!入江悠監督「ビジランテ」記者会見

- 入江悠監督、新作『ビジランテ』記者会見で北野武からの影響に言及「10代のころに衝撃を受けた」

- 入江悠 監督語る!! 北野武の”暴力”描写に受けた10代の衝撃が出発点---日本外国特派員協会『ビジランテ』記者会見レポート

- 入江悠監督、出発点になったのは北野武映画の“暴力”『ビジランテ』日本外国特派員協会レポート

Read more

Published in: November

Tag: Yu Irie, 8000 Miles, Saitama, Nao Omori, Kenta Kiritani, family, neighborhood watch

Comments