When we talk about the “cost” of revenge, we invariably refer only to its psychological and physical tolls. This instantly makes Yoshihiro Nakamura’s The 47 Ronin in Debt — a title to be read literally, not metaphorically — a groundbreaking addition to the category of jidaigeki period films about loyal samurai exacting retribution for offences against their masters.

The versatile writer-director of cult hits like Fish Story and The Foreign Duck, the Native Duck, and God in a Coin Locker, as well as commercial hits like Golden Slumber, A Boy and His Samurai, The Snow White Murder Case, Prophecy and The Magnificent Nine, Nakamura has taken a unique approach to adapting one of Japan’s most oft-told historical tales, “Chushingura.”

Although the tragic real-life incident has already been adapted to stage and screen hundreds of times, he has now boldly reinterpreted it not only as a comedy of sorts, but also as a fiduciary thriller. Surely both are firsts in the “Chushingura” canon.

Shinichi Tsutsumi balances humor and pathos perfectly as Ako chief retainer Kuranosuke Oishi.

©2019 "The 47 Ronin In Debt" Film Partners

The idea came from Shochiku producer Fumitsugu Ikeda, with whom Nakamura had worked on 2016’s The Magnificent Nine, a samurai comedy that also has serious themes at its core.

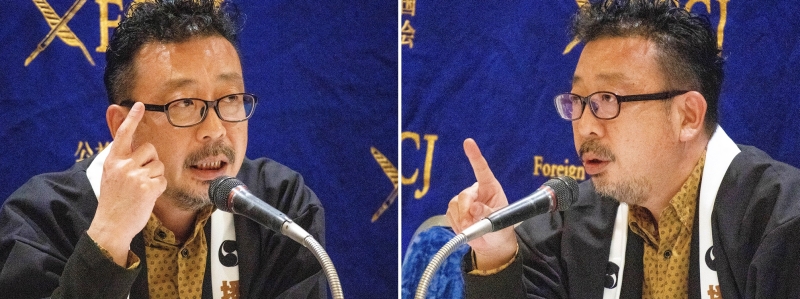

As the director told FCCJ’s audience following a sneak peak of his new film, “It’s widely known that the story is a tragedy, but I wasn’t familiar with all the details. So I first spent about 3 or 4 months ingesting all the books and films about it. The more I read, the more I realized how difficult it would be to turn into a comedy. So I decided not to tackle the legend but to focus instead on the Ako Incident, basing the story on the actual account ledgers of the Ako clan, which were kept by the chief retainer, Kuranosuke Oishi.”

Nakamura had come across a 2012 nonfiction work by University of Tokyo historiographer Hirofumi Yamamoto, who analyzed period records pertaining to the 1701-1703 planning and execution of the revenge plot, and used them to reconstruct the timeline of events.

©Koichi Mori

“Oishi kept track of the Ako accounts. During the [two-year period of planning for revenge], they spent ¥100 million on 113 items, all of which were in the balance sheets.” he explained. “The legends tell us that Oishi had a lot of foresight and was very strategic. But when you look at what actually happened and the balance sheets he left behind, you find a character who’s quite different, and that’s what we’ve brought to the screen.”

Nakamura’s approach admittedly favors a Japanese audience, who are overly familiar with the story and the dozens of main characters, and thus won’t find the film’s multiple monetary and name captions distracting. In a roundabout way, he was asked whether he might have worried it become one of those only-for-Japan titles.

“My previous films have been invited to international film festivals, and I’ve heard enthusiastic audiences laughing during screenings,” Nakamura began. “When I was editing, I would even intentionally leave some space in the films for [the anticipated] laughter. But with this film, we did not have an international audience in mind, because we knew it was so dense with information. It’s the first time I’ve approached a film this way.

Shochiku is cleverly billing the film as “budget attainment entertainment.” ©2019 "The 47 Ronin In Debt" Film Partners

“We were invited to the Tokyo International Film Festival last month, so we had to subtitle it. When I did a screen check of the subtitled version, I realized how challenging it would be for international audiences to watch it. So I must thank you for [taking up the challenge] of watching it tonight.”

Asked why he’d chosen the unconventionally jazzy soundtrack rather than a more traditional score, the director said, “This was my plan from the beginning. There were jidaigeki TV shows back in the 70s that used this kind of music and to my ears, it’s a good fit.”

The music certainly emphasizes the film’s comedy elements, which arise primarily from the relentless focus on finances. While the many previous screen iterations of “Chushingura” (directed by the likes of Shozo Makino, Kenji Mizoguchi, Kon Ichikawa and Kinji Fukasaku), have been all about the samurai code of honor, loyalty and self-sacrifice, Nakamura’s is all about the money.

©Koichi Mori

The screen is sometimes awash with captions detailing the Ako clan’s expenditures for everything from actual salaries, uniform costs and travel expenses to a night out in the pleasure district for 20 rowdy warriors. These have been helpfully/humorously converted into today’s equivalents in yen (and in subtitles, dollars) based on the cost of a single bowl of soba noodles ($4.40).

How did Nakamura decide on that unit, one audience member wanted to know. “We considered many items,” he responded, “including the price of a bowl of rice or a per diem paid to carpenters. But we ultimately decided on soba. The Edo period lasted for 260 years, and the price of a bowl of soba was the only item that remained unchanged in that time.”

Even a bowl of noodles is pricey when there are too many mouths to feed. ©2019 "The 47 Ronin In Debt" Film Partners

The 47 Ronin in Debt opens when Ako Lord Asano (Sadawo Abe) is at the height of a rather overzealous anti-corruption crusade. In 1701, he draws his sword on Lord Kira rather than pay him the expected bribe, and this results in his forced seppuku. Asano’s righthand man, Kuranosuke (a very good Shinichi Tsutsumi), is left to organize revenge with the fallen lord’s other devoted retainers. But the Ako must immediately surrender their castle, thus ending their tidy allowances and bringing their once-proud clan to the verge of bankruptcy. Kuranosuke’s immediate concern instead becomes to maintain solvency. There is just $877,000 in the treasury, and with 50 members of the clan plus their families, servants and his own concubines, the chief retainer soon realizes that his abacus-wielding accountants are mightier than any warrior.

Without them, attempts to win the shogun’s support for a restoration of the clan’s holdings cannot be properly financed, nor can anything else be accomplished. Yet as the days stretch into months and plans for vengeance remain just that, the samurai prove they will be spendthrifts. As the coffers are further drained and insolvency begins to engulf the Ako, Kuranosuke sees no other choice but to embrace the plan to assassinate Kira… if only they can afford the weapons and battle outfits to do it right.

©Koichi Mori

Nakamura’s financial approach to the fateful years leading to the Ako’s revenge allows him not only to bring a fresh perspective to the tragedy and find a way into the comedy; it also adds a greater sheen of contemporary relevance. But the director declined to take the bait when questioned about the correlation, as a journalist noted Japan now “has the world’s highest debt.”

Said Nakamura, “It isn’t an intentional commentary on present-day Japan.” But he did note, “Back in the Genroku Era, it was the townspeople who put pressure on the Ako samurai to take revenge. And it was a time when the shogun, Tokugawa Tsunayoshi, was enacting onerous political policies.”

Nakamura, in a happi coat similar to the Ako clan's firemen finery, with the Japanese poster. ©︎FCCJ

Nakamura had mentioned that they’d needed to costume 130 samurai for the film, prompting a journalist to see the Ako clan ’s struggles as a metaphor for the act of filmmaking. Was that why, she wondered, there were almost no horses in the film?

“Horses are so expensive!” Nakamura laughed, admitting they’d had the budget for just a single steed. “I think you’re right that we can draw comparisons. In such a scenario, I suppose I would be the Sugaya Hannojo character (played by Satoshi Tsumabuki, he’s an aggressive type who constantly pushes his fellow samurai to attack). The producer would be Oishi Kuranosuke. When the assistant director would ask whether I needed a horse in a certain scene and I said Yes, the producer would later go to him and be very angry.”

But the producer is sure to forget all about that once the film debuts in Japanese theaters. It’s one of the two most hotly anticipated releases of late 2019 and is expected to finish in the year’s top 10 at the box office.

©2019 "The 47 Ronin In Debt" Film Partners

Posted by Karen Severns, Thursday, November 21, 2019

Read more

Published in: November

Tag: Yoshihiro Nakamura, Chushingura, 47 Ronin, jidaigeki, samurai, comedy

Comments