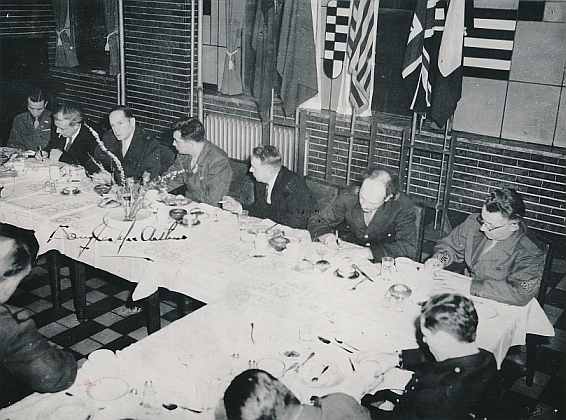

Adversity is often the trigger for organizing press clubs. So it was in September of 1945 when, soon after the Occupation of Japan commenced under General Douglas MacArthur, disgruntled war correspondents banded together for a common cause. They opposed restriction of the number of journalists permitted into Japan due to insufficient billets during those chaotic weeks following the surrender. This small group of correspondents quickly formed “The Tokyo Correspondents Club,” the forerunner of the FCCJ.

Faced with a lack of living quarters, the first objective of the new press club, headed by Howard Handleman (INS) with Don Starr (Chicago Tribune) and William Dunn (CBS) as 1st and 2nd vice-presidents, was to find a place to house correspondents coming to Japan. They found the war-battered, five-story Marunouchi Kaikan, derelict but still serviceable, located between MacArthur’s headquarters in the Daiichi Seimei building and Tokyo Station. This they leased and repaired to provide hostel services for some 170 correspondents, making it operational in November of 1945 even before repairs were completed. They called it “No. 1 Shimbun Alley.”

Located in Marunouchi, the district between Tokyo station and the Imperial Palace, the “Alley” was part of Mitsubishi Estate’s holdings that were later incorporated into one of those block-sized buildings erected after the Occupation. However, Marunouchi’s nearby central street, Naka-dori, stretching ten blocks between Otemachi and Hibiya, would continue to be the Club’s playground even after several moves. Not a bad place to be located, Naka-dori was convenient and destined to become Tokyo’s somewhat narrower version of Park Avenue. The fabled Ginza district was also within walking distance.

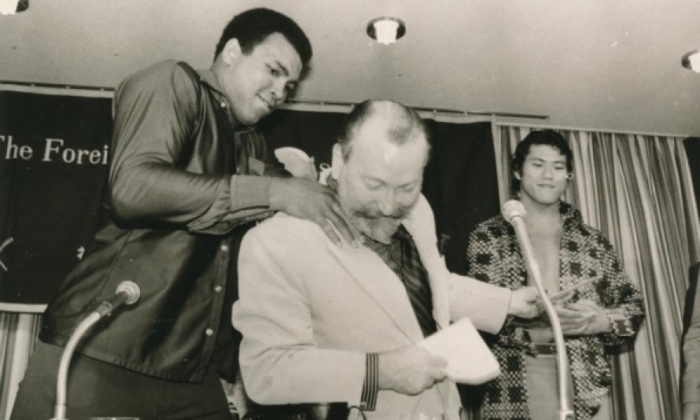

Of those early war correspondents, a dwindling number kept the world informed about Japan’s transformation under the Occupation, but by mid-1947 only 40 members remained. The Club was in straitened circumstances, with social events such as weekly dances and special dinners introduced to generate revenue toward the end of the 1940s. Then, in June of 1950, the Korean War broke out. Correspondents once again surged into Japan to cover that conflict, and Club membership jumped to a high of 350. Eighteen correspondents who died in the Korean conflict are memorialized on a plaque in the Club’s entryway.

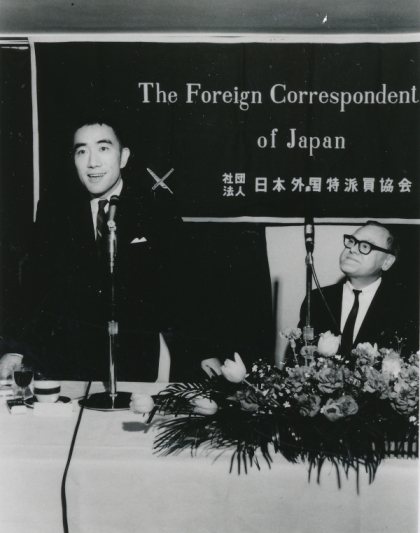

Sovereignty returned to Japan in 1952, bringing the Club under Japanese law. It changed its name to “The Foreign Correspondents’ Club of Japan” (FCCJ), and became a non-profit incorporated association (shadan hojin) sponsored by Japan’s Foreign Ministry. But declining membership again became a problem following a rapid drop-off in correspondents after the 1953 Korean armistice, which led the Club in 1954 to move into the vacated American Club premises on a nearby corner property facing on Naka-dori. This move altered the character of the Club; the hostel atmosphere became a fading memory and there was a rapid increase in Associate members.

The Club from its inception has been run by Regular members, correspondents assigned to Japan who elect from among their peers Club officers and Board directors as well as volunteers to participate in the many committees that make the Club viable and interesting. Associate membership, initially for family members, was a separate category from the first Club constitution in 1946. …

Relocation came again in 1976, this time to premises with a view. The 20th floor of the Yurakucho Denki Building on the corner of Naka-dori and Harumi-dori, the broad street separating the Marunouchi and Hibiya districts where it enters the Ginza area, became our new home. …

(photo by Sadayuki Mikami, AP)

Calamitous news in 1995 in the form of the Great Hanshin Earthquake that destroyed Kobe in January and the Aum Shinrikyō nerve-gas attack on a Tokyo subway in March caught the world’s attention. …

Despite changes, the FCCJ remains one of the oldest, largest and most active press clubs in the world in which journalistic ambience and the spirit of camaraderie remain alive and well. The membership stands at some 1,500 …

The Club history, Foreign Correspondents in Japan, provides details and insights of the FCCJ’s development over its first 50 years, from 1945 to 1995.