Two salarymen producers and a theatrical producer formed the creative team for an extraordinarily unusual film. Ono, Enoki and Yamamoto obviously enjoyed the process.

In his introduction before the screening of his beautiful and enigmatic Anohito: The One, Ichiro Yamamoto said that he had shown the film three times before, and that he had not received any comments at all from his audiences. So he wanted everyone to feel no pressure; he would understand if FCCJ’s audience didn’t have any feedback for him.

The remarks were so unexpected, and his delivery so comical, that the audience giggled — but Yamamoto was not exaggerating. At least not overly.

After a long career as a self-described Shochiku “salaryman,” working on productions for such illustrious directors as Nagisa Oshima and Seijun Suzuki, and producing award-winning work by Yoji Yamada and Hou Hsiao-Hsien, Yamamoto makes his own feature debut with Anohito: The One, and “strange” is an appropriate tag for the film’s many bewitchments.

A beautiful tribute to the heyday of Japan’s studio system, it also underscores how little has changed in Japanese society in the intervening years. As critic Tony Rayns has put it, “Anohito is a unique film which offers a subtly disquieting vision of the present through the mirror of the past.”

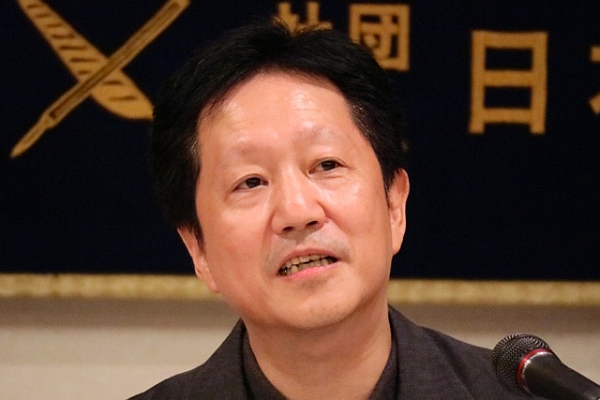

Yamamoto reveals the many secrets hidden in plain sight in the film.

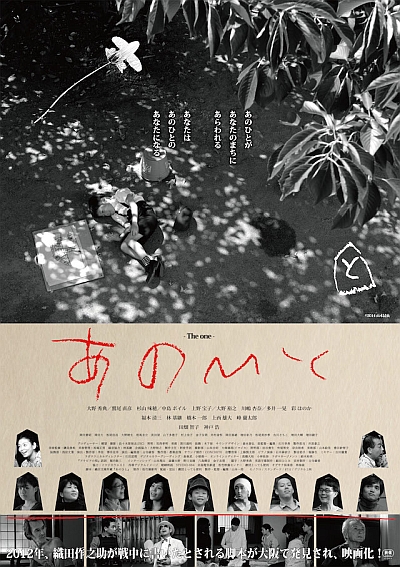

The director himself only half-jokingly describes it as “a sci-fi film produced and cast in 1944, imagining a future Japan 69 years later in 2013, where the Second World War still rages on.” Looking very much like a 1944 film, with its luminous black-and-white cinematography and its aspect ratio of 1.33:1, it nevertheless feels utterly modern in its concerns and sensibilities.

It is a seriously serious film, the outgrowth of a lifetime of cinephilia on Yamamoto’s part, and it grows ever more profound and endlessly multilayered upon a serious discussion of its attributes.

Fortunately, the FCCJ audience was in the mood for just such a discussion. But the evening was heavily punctuated with laughter, too, as questions ranged from the film’s antiwar messages and its unusual provenance, to the many octopus images, the enumerations of the number 8, the frequent appearance of shogi pieces and the reflections of water in every single shot.

The script is attributed to the famed Buraiha writer Sakunosuke Oda, and had been completed in 1944 for director Yuzo Kawashima but then lost, Yamamoto explained, until its 2012 discovery in a library in Osaka. After he’d read it and returned to Tokyo, he said, “I immediately asked my boss if we could make the film. And my boss immediately said No.” Shortly afterward, he continued, “I got an email from my department saying I had 5 days off, since I had worked in Shochiku for 20 years. I also had 5 days off for summer vacation. So I thought, if I can make the film myself with my savings of ¥20,000 a month for 20 years — that’s ¥5 million — I should. So I decided to get a producer. [a beat] It was the first time I noticed that the producer is so important.”

Enoki discusses the contributions of Shochiku's Uzumasa Studio to the film's look and feel.

Yamamoto turned to his fellow Shochiku producer, Nozomu Enoki, because “he’s the strangest guy in Shochiku,” and enlisted the support of actor-playwright-producer-author-Charlie Chaplin specialist Hiroyuki Ono, “the strangest guy in Kyoto,” for the cast.

Enoki stressed, “Five million yen is quite a small budget for making a film, maybe 1% of our typical production budget. But I was working at Shochiku’s Kyoto studio and … with the help of the veteran crew members there, I thought we could get this made.”

The film looks remarkably sumptuous, given its pricetag — its most expensive shot, Yamamoto revealed, was a CG octopus-shaped battlefield scar on one of the characters — and evokes nostalgia for the artistry of yesteryear not only in its cinematography, but in its mise-en-scene and its many musical interludes, which may or may not be propaganda songs of the day. Enoki explained that the Kyoto Uzumasa Studio “has a long tradition of making samurai films, and we have a lot of props that we were able to use in the film. Mr. Yamamoto’s intention was to conflate the styles of Shochiku’s Ofuna Studio period and the Uzumasa Studio films, and our creative team understood that.”

Ono talked with passion but no crab bubbles — you'll have to see the film to get the significance.

On the surface, Anohito: The One tells the story of four young soldiers working menial jobs so they can raise the orphaned son of their commanding officer (“Little Commanding Officer,” they call the boy) in a forgotten town populated by the war’s leftovers: women, children, lonely old men. The women are constant targets for the local matchmaker, and are often reminded that life is more difficult for them. The soldiers seem to be speaking dialogue that they’ve heard elsewhere, such as their chant, “Cheer up and brighten up! Sprout out and grow!” After hearing unpleasant news about the war on the radio one day, they leave the boy with an aging cook, and go off to work in munitions factories, promising to be home for new year’s. The cook invites the woman next door to move in, then disappears himself, leaving a message for “The One…”

Who is “The One?” For Yamamoto, he is unequivocally the boy, given the absence of any ancestral photos in the family home and the fact that he does nothing, while all the other characters wait on him. “I doubt his father exists, and my conclusion is that the boy is deceiving people. This means that he is manipulating the whole town to go out and support the war.”

Stepping out from behind the scenes for well-deserved applause.

For Ono, who brought in key cast members from his Tottemo Benri theatrical company and enacted a role himself, there are other possible interpretations of Oda’s script. “At first glance, it may seem like a warmongering film — let’s get back into the military factories — but we get a strange feeling when reading it, as if Mr. Oda was trying to hide an antiwar message.” He went on to explain that the boy’s name is “Kamiya Shoichi: ‘Kami’ is, of course, ‘god’ in Japan. ‘Sho’ is for ‘Showa,’ the name of the era of Emperor Hirohito, and ‘ichi’ means ‘the first.’ So perhaps the boy is a metaphor for Emperor Hirohito. It’s one of the interpretations, anyway. We don’t know what Mr. Oda intended.”

As Enoki wrote in the film’s production notes: “There is a strange ineffable force, almost like atmospheric pressure, that controls these people. We wanted to investigate ‘The One’ who was somehow applying this pressure, for surely we still feel the overbearing presence of ‘The One’ to this very day.”

The film is making its international debut in the Youth on the March competition at the 22nd Minsk International Film Festival, Listapad, to be held in the capital of Belarus during the first week of November. The festival is renowned for its cinema-as-art bent, but audiences are in for a rare treat with this One.

— Photos by Koichi Mori and FCCJ.

©2015 Yamamoto Konchu

Posted by Karen Severns, Wednesday, October 21, 2015

Read more

Published in: October

Tag: Ichiro Yamamoto, Nozomu Enoki, Hiroyuki Ono, awardwinning, WWII, antiwar, Sakunosuke Oda

Comments