It’s not often that the Film Committee is able to host what amounts to the Japanese premiere of a brand new work, but such was the case with our screening of Artist of Fasting. The FCCJ audience also had the privilege of welcoming not only the director, Masao Adachi — who had missed the world premiere in South Korea a few weeks earlier — but also two of his famous friends, poet Gozo Yoshimasu and cultural historian Inuhiko Yomota.

The Q&A session began with a riveting live performance of a poem by Yoshimasu that was an extension of one that is memorably performed in the film. The renowned poet noted that, “My participation and collaboration with Mr. Adachi was with the utmost respect for a filmmaker of our generation, one of the best filmmakers of our generation, and this allowed me to extend my poetry to the film.”

Three good friends; three comrades united in the belief that art is a form of protest.

Commissioned and coproduced by the Asian Arts Theatre of Gwangju, South Korea, Adachi’s film had debuted at AAT to great acclaim on September 11. But as writer William Andrews explained on his blogsite: “Appropriately for a venue hosting an Adachi work, Gwangju was also the site of a notorious student uprising in May 1980 in which 600 people were killed by the army. Adachi famously has no passport and cannot travel abroad anymore. While Gwangju is much closer than Lebanon, he still [wasn’t] able to attend the screening in person.”

Arguably the most radical filmmaker in Japanese history, Adachi launched his career in politicized pink films in the 1960s, collaborated with the likes of Nagisa Oshima and Koji Wakamatsu and achieved global renown for such works as AKA: Serial Killer in 1969 before he chose to focus on the fight for Palestinian independence. From the early 1970s, he spent 28 years in Lebanon as a member of Fusako Shigenobu’ s Japanese Red Army, culminating in a 3-year term in the notorious Roumieh Prison and deportation back to Japan in 2000.

Yoshimasu and Yomota watched the film for the first time with FCCJ's audience.

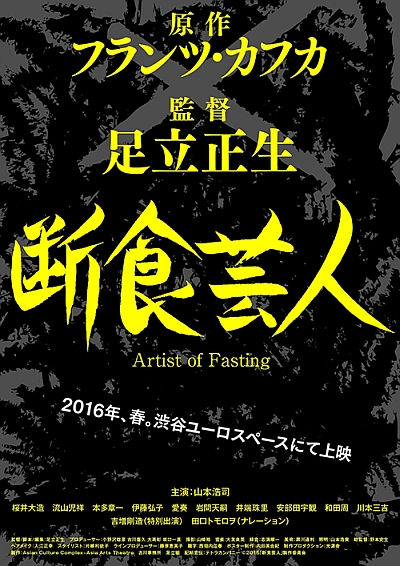

Artist of Fasting is just the second film Adachi has made since his return. A loose adaptation of Franz Kafka’s 1922 short story Ein Hungerkünstler (A Hunger Artist) about “the last remaining means of resistance: fasting,” the director proves his youthful instincts for provocation and transgression have not dimmed.

In the beautifully lensed (by renowned cinematographer Yutaka Yamazaki) and impressively designed (by legendary photographer Nobuyoshi Araki) Artist of Fasting, a nameless man in white appears from nowhere and sits down on a busy shopping street. A boy soon asks, “Mister, what are you doing?” Receiving no answer, he takes a photo and uploads it to the internet. The sitting man’s unearned celebrity grows, and his silence is interpreted differently by every passerby and onlooker that begins to gather. People bring cash (later grabbed by the yakuza) and food (which the homeless descend upon). The Street Performers’ Association force him to join them; monks begin to pray at his side, seeking answers; suicidal youths feel soothed in his presence; the press wants to know if he’s a victim of Abenomics. Eventually, the man is caged and given an army guard.

In inimitable Adachi style, the tale unfolds around the faster’s “performance,” but also comprises abrupt avant-garde interludes (scenes of Imperial Japanese and ISIS torture), as well as archival footage of victims of aggression (Ainu, Auschwitz). There are rapes, murders, necrophilia, group seppuku, nude dancing, enormous phalluses, feces eating. In short, Artist of Fasting encompasses every conceivable ill of modern society.

Asked why he’d chosen the story, Adachi explained: “Among the many works of Kafka that are open to interpretation, I like A Hunger Artist very much because it’s a satirical, humorous tale that reminds me of rakugo. Of course it’s not an easy kind of humor, and we can’t just laugh it away. But facing the situation in 2015 today, I felt that it was the type of story that could be made into a film, and that I could [be the one] to do it. I had a lot of fun making it.”

Yoshimasu noted that, “Kafka was in a sanatorium, dying of TB, when he was editing this story. And I feel as if, in an invisible way, Kafka’ s spirit was in this film.”

Agreeing with one audience member that the film has no easy interpretation, Yomota likened its protagonist to the subject of Beatles song Fool on the Hill, and its black humor to Monty Python’s. But he also expressed his gratitude to Adachi for shining a spotlight on serious issues. “In Tokyo exhibitions in the

previous century,” he said, “there was something called the Humanity Pavilion. Like in a zoo, they exhibited Japanese ethnic minorities, such as Ainu and Okinawans, and they were regarded as barbarians, uncivilized, who had to be naturalized to become real Japanese. It’s a scandal, and it’s a great thing that Adachi has now depicted this case in our contemporary context. It’s important to remember that, 100 years ago, the Japanese government’s cultural policy was to treat racial minorities like animals in a zoo.”

Over the past decade — but particularly over the four years since the triple tragedies on March 11, 2011 — the boundaries between art and social activism have collapsed in Japan. Today’s artists are expected to be more politically active, and artist-activists have been emboldened to take a stand and join (or lead) the ongoing public protests for the first time since the 1960s.

Asked whether he sees the position of the artist as freer today than in the past, Adachi answered, “People say that history always repeats, but my feeling is that it will never be as bad as in the past. There are, of course, unbelievable things happening today. But I do think they all happen so we can keep going forward. As you know, I’ve been on business overseas for a long time [his preferred euphemism for time spent in Lebanon], and I do believe that revolution and cinema are one and the same. [scattered applause] That means that the work of the artist and the terrorist are one and the same, and we still have a lot to do.”

Yomota summarized succinctly: “The journalist-Hollywood filmmaker Samuel Fuller told me that optimism always defeats pessimism.”

— Photos by FCCJ.

©2015 A Fasting Artist Production Committee

Posted by Karen Severns, Saturday, September 26, 2015

Media Coverage

- Adachi Masao, un artista del hambre

- カフカ題材×足立監督の怪作!警官、マッドナース、監獄、宗教家…幻想的イメージの連続

- 足立正生監督、9年ぶり新作はカフカ「断食芸人」を映画化

Read more

Published in: September

Tag: Masao Adachi, Franz Kafka, artist, activist, protest, international coproduction

Comments