Members of the elite Toei Tsurugikai gave a dazzling live performance after the screening, and then struck ferocious poses with Nakajima (center) and Seike (left). These highly trained swordsmen and women are the real stars of Kyoto’s action films, putting the thrills and chills into the fight scenes, and elevating the performances of the top-billed stars. ©Mance Thompson

The term sensei is often wielded too lightly in Japan, a catch-all title meant as a demonstration of respect for one’s elders and/or betters that seems to find its way onto the end of altogether too many names, whether deserved or not.

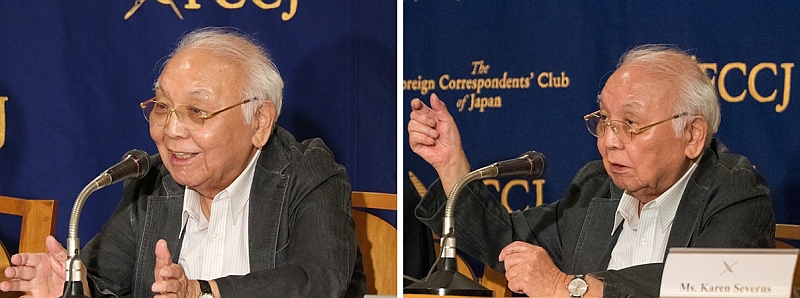

But sometimes, the title fits perfectly, and Sadao Nakajima — always “Nakajima Sensei” or “Professor Nakajima” — wears it well. A veteran Toei director, having helmed over 60 films in nearly 60 years in the industry, he is a cult figure, a fount of knowledge, a veritable walking encyclopedia of chambara lore. (Speaking of walking, to see the 82-year-old stroll into FCCJ’s screening room is to see the picture of crackling-with-youth energy, and it seems certain that his cane is just for show — perhaps, I imagined, there was a hidden blade inside, just like the shikomi gatana carried by one of his characters).

The professor speaks to a rapt audience. Photo left ©Koichi Mori; right ©Rob Nava-Moreno

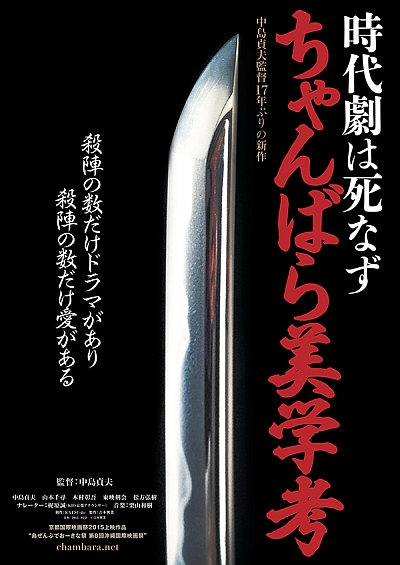

In his new documentary, Chambara: The Art of Japanese Swordplay, the professor proves to be not only an impassioned scholar, but also a most affable screen presence, as he relates milestones in the history of Japan’s homegrown swashbuckler film (chambara being the sound of clashing swords), and trades anecdotes with an array of authorities (swordfight artists, actors, armorers, historians, critics). A must-see for all fans of spectacular swordsmanship, Chambara is also a veritable master class in everything jidaigeki (samurai period) film, providing just the layman’s approach necessary for those of us (ahem, guilty) who have remained willfully ignorant of the medium’s many delights.

As we learn, Japan’s first-ever jidaigeki was screened in Kyoto in February 1908. Directed by the great Shozo Makino, an industry pioneer whose son Masahiro would become Nakajima’s mentor, the one-reel drama featured kabuki actors in the roles of rival samurai. Almost nothing of Makino’s work has survived, but the swashbuckler continued to flourish with the rise of the samurai, ninja and yakuza genres.

The Toei Tsurugikai in action. ©Mance Thompson

As he traces the origins and growth of the Kyoto-centric industry, Nakajima treats Chambara viewers to rare footage from a wealth of early and later films, and compares the styles of the major stars of each era, from Matsunosuke Onoe (“Medama Matsu”), Tsumabasaburo Bando (“Bantsuma”), Chiezo Kataoka, Utaemon Ichikawa and Arashi Kanjuro (“Arakan”) to Raizo Ichikawa, Jushiro Konoe, Kinnosuke Nakamura, Shintaro Katsu and Hiroki Matsukata. Naturally, much screen time is also devoted to the enormous impact of Akira Kurosawa and Toshiro Mifune on the genre (not all commentators view it as positive).

At its peak in the late 1950s, there were 100 professional swordfighters working on Kyoto’s sound stages, and jidaigeki would account for over 150 film releases each year. But those days are done. In Ken Ochiai’s elegiac Uzumasa Limelight, which we screened at FCCJ in 2014 (and in which Nakajima has a small role essentially playing himself), we see that the skilled bladesmen of Kyoto are running out of work as the jidaigeki industry dries up. It’s no wonder that the swordsmen and women of the Toei Tsurugikai, an elite team started in 1952 at the Kyoto Toei Studio to develop tate, or chambara techniques using kata swords, now number very few, and must support themselves in a variety of realms, not just on film.

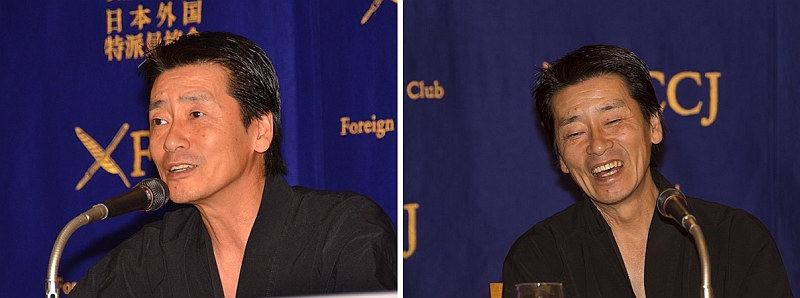

Famed fight choreographer Mitsuhiko Seike. Photo left ©FCCJ; right, ©Mance Thompson

Not surprisingly, the first questions asked of Nakajima and famed fight choreographer Mitsuhiko Seike after the screening of the documentary concerned the future of jidaigeki. Both men were fairly upbeat. Seike noted, “While it’s true that the number of chambara films are decreasing year by year, we have the Jidaigeki Senmon Channel on cable TV, which specializes in jidaigeki programming. Often they air classics and reruns of old shows. But in the past few years, they’ve started producing their own shows. These are sometimes adaptations of classics or jidaigeki manga, or they’re series based on famous novels. They feel slightly different from what we used to see, but I think that’s one avenue for the future of the genre.”

One journalist commented: “This movie’s full of old men complaining about how good times will never come back. But Chihiro Yamamoto, star of Uzumasa Limelight, is in the film, and tonight we’ve just seen a demonstration in which a woman struck down three men. So is chambara’s future perhaps in women’s hands?”

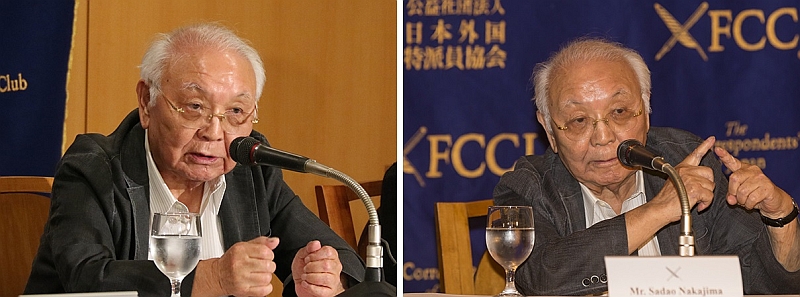

Photo left ©Koichi Mori; right ©Mance Thompson

Nakajima nodded and admitted, “It’s true that the films have been male centered. After the war, they became much more conscious of the female audience, but the strange truth is that in Japan’s history, especially during the Muromachi Period, women really shined in real life. Unfortunately, that hasn’t been portrayed in films enough, except in the o-oku stories about the harems in the inner chambers of the shogunate. I started the whole series of o-oku films, and yet the sad fact is that these women are still seen from the perspective of men, and the films tend to be tragedies. Even with a female protagonist, they’re still seen through the prism of the male gaze.”

He continued, “But we’ve seen a lot more women being interested in history [the so-called “female history buff” or rekijo, trend that many have seen as empowering for young women], and there are many young women who are drawn to the Japanese sword … and the chambara culture in general. So I think that’s encouraging.”

©Mance Thompson

To a suggestion from the audience that Toei should consider launching a “jidaigeki renaissance,” and hire young directors to reinvigorate the genre, Nakajima responded, “I don’t see Toei doing that. Financing both production and distribution in Japan is often under the same umbrella, so everyone wants to do what’s most profitable for the least risk. They only invest in what is very safe. Those of us in the older generation must create an environment in which [chambara] filmmakers feel they can thrive, and perhaps we should provide case-study examples of how these films can succeed. I’ve been asking myself how I can best create that kind of environment for younger filmmakers to be able to carry on the torch.”

Chambara: The Art of Japanese Swordplay reveals the secrets of how those shiny stage kata are made, and discussion returned several times to these potent symbols of the samurai soul. One audience member asked whether real swords were ever used. “Yes,” said Nakajima, to audible gasps from the audience. “But never to swing them. I used them to capture the light reflected on the blades, but we would never use them in action. It’s simply too dangerous. When you see and handle a real sword, you’re confronted with how frightening it is. It’s too intense and emotional. There’s a power that Japanese swords have, and we can’t imagine swinging them around in a movie.”

In the old days, noted an elderly audience member, “we didn’t hear the sounds of slashing and we didn’t see so much blood. Why did this change? Have chambara been pursuing an ever-greater level of reality to make them more popular today?”

Nakajima explained that the sword material itself had changed. “During the postwar period, they used takemitsu, basically wooden swords made from a type of oak,” he said. “The sound on set was thus the blunt sound of wood on wood. We didn’t replace them with sound effects. It wasn’t until 1960 or so that we started replacing the sound with something more metallic. There hasn’t been much evolution since then… But we have to remember that the world was a different place in the period in which jidaigeki are set, and they could hear things — the sound of geta, or the wind blowing — that we hear in a different way today. Most of these sounds have now been wiped out by music on the soundtracks, too.”

Added Seike, “Today, a lot of the blood is done with computer graphics, but we still use pumps and fake blood, and often, we try something different with them. But you’re providing entertainment for the audience, and it’s difficult to answer the question of ‘what is most real?’ I have no doubt that some films will continue to experiment with what works best for a particular film, but I don’t see this as an industry-wide trend.”

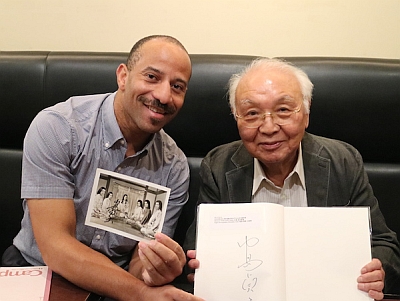

Mance Thompson, photographer and ninja specialist,

gets Nakajima's autograph. ©Koichi Mori

After mentioning that jidaigeki once attracted the biggest talents from literature and theater, a situation that is glaringly different today, Nakajima obliged one audience member with a recommendation for a couple of films to watch: “I think Samurai Hustle I and II are good, because even though they don’t have much chambara action, they really show what it was like to be a samurai, and show a new aspect of what jidaigeki can do. The action sequences aren’t too exaggerated; they maintain a certain reality. I think this offers a new direction for jidaigeki.”

Although he didn’t say it, Sadao Nakajima surely hopes that Chambara: The Art of Japanese Swordplay can also play a role in suggesting new directions. At the very least, it should help swashbuckle up interest in the genre among younger generations, as well as among those, like me, who didn’t realize quite what they were missing until now.

©Yoshimoto Kogyo

Posted by Karen Severns, Friday, September 16, 2016

Media Coverage

- 中島貞夫監督 82歳で新作!映画界の現状憂いバッサリ「作り手側の意欲の問題」

- 中島貞夫氏「歴女」に時代劇盛り上げ役として期待

- 中島貞夫監督、時代劇の未来は女性にあり「刀に魅せられる女性増えた」

- 中島貞夫監督、最新作「時代劇は死なず ちゃんばら美学考」の試写会に出席

Read more

Published in: September

Tag: Sadao Nakajima, chambara, jidaigeki, samurai, Kyoto, Uzumasa Limelight, documentary

Comments