“Unconventional” is an adjective that describes nearly all of Naoko Ogigami’s characters, from the Japanese women who open a washoku restaurant in Helsinki (Kamome Diner, 2006) to the frazzled city dweller who learns how to “twilight” on a quaint island (Megane – Glasses, 2008), to the grandmother who longs for a Toto Washlet while living overseas (Toilet, 2010), to the young woman who rents cats to people who need pet therapy (Rent-a-Cat, 2012).

So it comes as a surprise that while the writer-director’s first new film in 5 years, Close-Knit, includes its share of unconventional characters — including a transgender woman as the protagonist — it is really her most conventional work yet, if “conventional” is understood to mean “sure to appeal to a broad audience.”

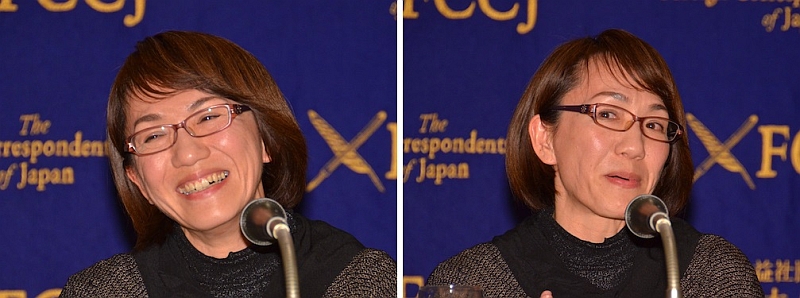

Appearing at FCCJ shortly before she was due to leave for the film’s world premiere at the Berlin International Film Festival, and speaking without an interpreter, Ogigami explained why Close-Knit feels different: “One of my challenges was, I’m really fed up with people calling my films iyashi-kei eiga [akin to ‘films that promote emotional healing,’ a genre that Ogigami has been credited with starting], and I wanted to do something new. I think I have done something new, and if it attracts a different audience, that’s great. My previous films were almost all fantasies, so I tried to make this more realistic.”

Perhaps it is Close-Knit’s serious consideration of LGBTQ (and other pressing social) issues that lends it a greater sheen of realism, although there are still several quirky characters and scenes with the director’s patented eccentric humor. The story of a very modern family, it begins when fifth-grader Tomo (Rinka Kakihara), is abandoned by her often-absent mother. Already resourceful, Tomo heads for her uncle Makio’s (Kenta Kiritani) place. There, she meets his beautiful girlfriend Rinko (Toma Ikuta), who warmly welcomes her and proves to be a much better mother than her own. But Rinko is transgender, and soon, Tomo is being bullied by classmates for her new “weird family" (among less gentle name-calling). When Tomo fights back and the police are called, Rinko helps calm her by showing her how to knit, and how to work out her anger with each stitch. Rinko herself has been knitting strange, colorful objects that she terms her “worldly desires.” When she has made a certain number of them, she says, she will conduct a “manhood memorial service,” and file papers to legally change her gender. With Makio and Tomo’s support, Rinko will not only reach her goal, but also be inspired to pursue a dream that she thought was outside her reach.

Ogigami admits she wanted a beauty for her leading lady, and she got one in Toma Ikuta. ©FCCJ

Close-Knit features a trio of extraordinary lead performances, two of them by major movie stars — Toma Ikuta (The Mole Song, The Top Secret: Murder in Mind) and Kenta Kiritani (Too Young to Die!, Gonin Saga) — marking the first time that Ogigami has cast big names. The third performance is by a complete unknown, preteen Rinka Kakihara, who more than holds her own.

Although she didn’t have Ikuta and Kiritani in mind when she wrote the script, Ogigami admitted that she knew “I needed [an actor with] a beautiful face, since he had to [convincingly] play a woman. The first time I saw Ikuta-san in a film was 7 years ago, and I was so impressed with how beautiful he is. So he was always in my mind. I finished writing and started thinking about casting, and I thought he would be good for the role. But he’s from Johnny’s [Jimusho, the notoriously controlling management company], and I thought even if I offered him the role, he would have to decline. But fortunately, he said, ‘Yes.’

“Once Ikuta-san decided to do this, I thought for his partner, I had to find someone taller than him, but with a [gentle demeanor]. When Kiritani-san was young, he used to play hotheads all the time, but as he got older, he started getting calmer, and I thought he would be good.” As for Kakihara, she enthused, “I found her at an audition. She’s an absolute genius. I had a lot of rehearsals with Ikuta, but not so many with Kakihara. This was the first time she’d been in a film, and she was just a natural.”

©Kochi Mori

Since the film “pushes social boundaries,” as one journalist put it, he found it surprising that the bulk of the budget came from status quo monolith Dentsu. “It was very hard to find financing,” admitted Ogigami, “because it’s based on an original story, and it’s very hard, nowadays, to make films [that aren’t based on bestselling novels or popular manga]. But Dentsu came aboard.” Asked if that was before or after Ikuta had signed on to the project, she laughed, “About the same time.”

Asked what had inspired the story, Ogigami said that she’d spent 6 years in Los Angeles during her 20s, and had had a lot of friends who were gay and lesbian. “When I came back to Japan, I didn’t have many friends who were sexual minorities,” she explained, “and that was awkward for me. I realized it’s still difficult for people to come out of the closet in this country. That was one of the reasons I made the film.”

An Argentinian journalist mentioned that her country had just begun educating teachers to treat trans children according to the gender with which they identify, thereby doing away with the longheld notion that they are abnormal. “In the film,” she noted, “Rinko’s mother completely accepted her when she was young, unlike the boy’s mother [a friend of Tomo’s who may be gay]. Did you base these characters on real people?”

Kiritani and Kakihara in the film. ©2016 ”CLOSE-KNIT” Film Partners

Ogigami responded, “I found an article in the newspaper about a transgender woman [Natsuki Majikina], who told her mother when she was 14 that she wanted to have breasts. Her mother knitted fake boobs for her. I went to her mother to ask her about this. She said she always knew that her daughter was different, but she always accepted her. On the other hand, I have a friend who’s gay and Catholic, and says that he will never tell his mother, as long as she lives.”

Asked about other research she’d done before writing the script, the director said, “Since I’m not a sexual minority myself, I was worried about whether I was allowed to make this kind of film. If I don’t have any prejudice or discrimination, I thought it would be all right. But I didn’t want to hurt anyone, so I asked my transgender and gay friends to read the script, to make sure no one was offended.”

Close-Knit is an apt metaphor for the film’s themes, referring as it does not only to the creation of new family ties and the bolstering of old ones, but also to the actual act of knitting — an important feature of the story that required several months of intense practice before filming commenced.

Noting that the film encompasses a number of important social issues beyond LGBTQ concerns — bullying, elder care, youth suicide, family estrangements and abuses that repeat from one generation to the next — one member of the audience suggested, “I think it would be great if families could see this film together.” It wasn’t entirely clear which definition of “family” he meant, but “the family of man” is just about right.

Posted by Karen Severns, Sunday, February 12, 2017

Coverage

- Naoko Ogigami’s latest film offers another take on the Japanese family

- Close Knit: Naoko Ogigami contra los prejuicios

- 『彼らが本気で編む時は、』(生田斗真主演)荻上監督作品!

Read more

Published in: February

Tag: Naoko Ogigami, Toma Ikuta, Kenta Kiritani, LGBTQ, transgender

Comments