Before she found the perfect title for her documentary, Laura Israel had planned to call it Robert Frank, You Got Eyes. As she explained to FCCJ’s Q&A audience, “Jack Kerouac wrote that in the forward to ‘The Americans.’ We always knew it was a working title, and I was never really happy with it because I felt it was too old and over-used already. But Robert came up with the title. He was answering a journalist who asked him, ‘What would you tell young photographers?’ He said, ‘Keep your eyes open. Don’t blink.’”

Heads nodded approvingly around the room, not only because many of those present were photographers themselves, but also because the words seemed positively Frankian: deceptively simple, enduringly deep.

The Swiss-born New Yorker revolutionized the art of photography and independent film in the 1950s, with work that was personal, impulsive and (purposely) imperfect. In his 60-year career, he has documented the Beats, Welsh coal miners, Peruvian Indians, the Rolling Stones (infamously) and of course, the Americans.

©FCCJ

Frank first came to fame in 1958 with the French publication of his seminal book “The Americans,” which was the result of a 9-month, 10,000-mile, 30-state journey through his adopted country (funded by a Guggenheim Foundation fellowship). Culled from 767 rolls of film and 27,000 images, the book’s racially-charged depictions of America’s downtrodden, lonely and marginalized, were haunting and controversial. One critic dubbed Frank’s work a “sad poem for sick people,” while another slammed the “meaningless blur, grainy, muddy exposure, drunken horizons and general sloppiness.” But “The Americans” is now considered the most influential photo book of the 20th century.

Frank’s sympathies have always been with “people who struggle,” and he has portrayed them with unfailing empathy, as well as unblinking honesty. Yet he has not been a willing subject himself. In one scene is Israel’s film, we see him, circa 1988, staring into a video lens. “I hate these f***ing interviews,” he complains to his interlocutor, getting increasingly irritated. Finally he growls, “I can’t stand to be pinned in front of a camera, because I do that to people. I don’t want it to be done to me!” And he gets up and walks out of frame.

But Don’t Blink presents a different side of Robert Frank. A sprightly 90 years old when the film was made, and a little more relaxed in front of the camera than he was in the 1980s, the irascible, reclusive subject of Israel’s immersive documentary reveals he has a surprisingly sanguine character.

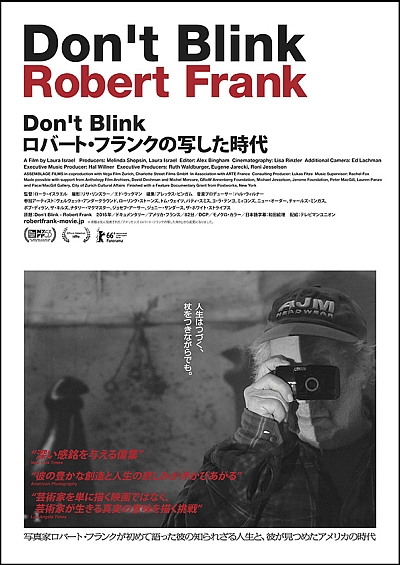

Photo of Robert Frank by Lisa Rinzler, copyright Assemblage Films LLC

It helps that the woman behind the camera is his long-time collaborator. Israel has been his editor and archivist-preservationist for nearly 30 years, and their intimacy has allowed her to tap into a staggering wealth of archival images and footage, as well as to capture Frank in a variety of settings over three years, from his New York loft to his isolated cabin in Nova Scotia.

Asked how the project came about, Israel explained, “I went with my first film [Windfall, 2009] to the International Documentary Festival Amsterdam, and [took part] in the mentoring program there. I met with a writer, Tue Steen Müller. He was kind of a gruff, older guy and had a lot of personality, like Robert Frank. He wasn’t particularly happy with my film [which looks at a small town’s troubles with wind turbines]. I was intimidated, so I told him, ‘I thought we would get along, because I work with Robert Frank.’ He lunged over the table at me and said, ‘That’s your next film! You’re doing a film about Robert Frank!’”

Photo of Robert Frank by Lisa Rinzler, copyright Assemblage Films LLC

Despite Israel’s resistance, and initially, that of Frank, the project took off just days after she mentioned it to him. And did he demand any changes, once the film was finished? “No changes,” Israel told the FCCJ crowd. “He said, ‘I really like the music, and you made the photographs come to life.’”

Don’t Blink is like a visual game of free association that pays tribute to Frank’s own style, cut together as if it were one of the restless artist’s frequent road trips, with rapid-fire montages of his photographic and film work, from his fashion-snapping years with Harper’s Bazaar and his freelance photojournalism, to his handmade-style films and his friendships with Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg and other assorted counterculture artists, as well as with the everyday people who continue to fascinate him.

Israel discussed the accomplishment of putting the documentary together. A veteran editor herself, she said, “I worked with an editor, which I would recommend to any filmmaker. It was a lot of footage, and Robert gave us access to all of his work, and he’s very prolific. We set up an editing room with all his books, all his photos, all his films, and we surrounded ourselves with Robert Frank for a year and a half. It was wonderful. But when we see the film now, we look at each other and say, ‘Whew. I’m glad we don’t have to do that again!’”

©Koichi Mori

One journalist asked about the impact of the 9/11 terrorist attack on Frank’s life and work, and why it wasn’t included in the film. “Robert wasn’t in New York around 9/11,” responded Israel. “He was in Nova Scotia, and he returned immediately. He brought back that beautiful film about the guy who delivers papers [Paper Route, 2002; excerpted in Don’t Blink]. I had been there on the Lower East Side on 9/11, and that film means so much to me. After 9/11, seeing that simplicity and beauty and that kind of life really helped me. It was very cathartic to work on that film, editing with Robert.”

It turned out that Frank wasn’t the only fan of the film’s soundtrack. With each subsequent audience question, the filmmaker was praised for her musical choices. Asked how she managed to afford so many well-known names, Israel explained, “I worked with a wonderful music producer, Hal Willner, and his associate, Rachel Fox. After Hal saw the first 30 minutes of the film, he was very excited and said, ‘Okay, I’ll call up Bob Dylan’s manager.’” And I was like, ‘Okay, go ahead and do that and we’ll see how that goes.’ [laughs] He called me the next week and said, ‘Bob Dylan said yes.’ After we got Bob Dylan, it seemed that all the musicians, either by design or by pure luck, had a connection to Robert Frank. This was the rare project where you call and ask someone for a favor, and they thank you for calling and asking them to help.

Israel with the film's Japanese poster. ©FCCJ

“Let me give a few examples: Charles Mingus — someone told us ‘Sue Mingus [his widow] never gives his music to any film. You’ll never get that music. Never, ever.’ Then we found out that Robert actually introduced her to Mingus, and he was at the wedding and everything. So she said yes right away. Yo La Tengo — I didn’t know until later that they had done a song called ‘Pablo and Andrea’ [the names of Frank’s two children, who died tragically young], and that they had gone to school with them [at the school featured in Conversations in Vermont, 1969]. Tom Waits — we found out that he was very excited about the one song we used. So we said, ‘We’ll use two, then.’ And the Kills — I really love the song ‘The Way New York Used to Be,’ and we approached Alison Mosshart, and she said ‘I would do anything for Robert Frank. I would never say no to Robert Frank.’ So all these things fell together.”

The ranks of Robert Frank fans are bound to swell after the Japanese release of Don’t Blink, although he has long had a devoted following here. Impressive not only for its historical immersiveness, the film also delivers positive messages about aging and creativity. Frank has continued to create at an exhaustive pace, embracing work for its energizing and its healing properties, and is still finding new stories to tell about his fellow outsider Americans. “These are good people,” he says, “these marginal people who live at the edge. They interest me. ” And then he snaps another shot to add to his one-of-a-kind collection.

Photo of Robert Frank by Lisa Rinzler, copyright Assemblage Films LLC

Posted by Karen Severns, Saturday, March 25, 2017

Press Coverage

Read more

Published in: March

Tag: Robert Frank, Jack Kerouac, Laura Israel, documentary

Comments