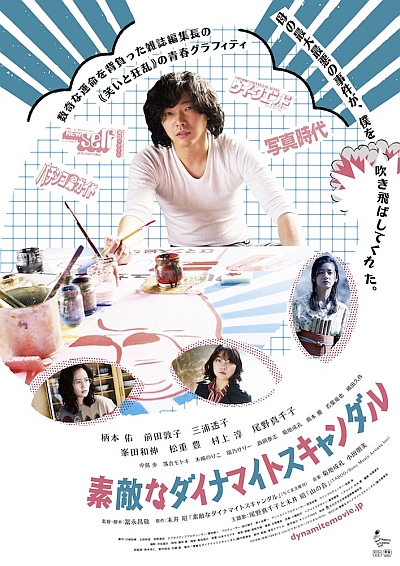

Just two months shy of Akira Suei’s 70th birthday, writer-director Masanori Tominaga is releasing his biopic of Japan’s 1980s porn-magazine king. Known for unconventional dramas with edgy characters, convoluted plotlines and dashes of dark humor (see The Pavilion Salamandre, Vengeance Can Wait, Rolling and last fall’s Pumpkin and Mayonnaise), Tominaga’s latest film is all those things. But it is also a considerably lighter affair: a surprisingly G-rated treatment of an often X-rated subject.

And if you never quite believed that truth is stranger than fiction, Dynamite Graffiti will surely be your corrective.

Suei’s utterly improbable but true adventures in the skin trade began during the early years of the bubble era. Then a struggling illustrator, he discovered he could make more money in the erotic publishing business than painting signboards for Tokyo’s increasingly naughty cabarets. By the early 1980s, he had become the Hugh Hefner of Japan, editing in quick succession three best-selling pornography magazines: New Self, Weekend Super and Shashin Jidai (Photo Age). Remarkably uninterested in porn himself, he focused instead on printing the work of distinguished writers like Genpei Akasegawa, copywriter Shigesato Itoi, editor-illustrator Sinbo Minami and photographers Nobuyoshi Araki and Daido Moriyama, earning them international renown and bringing unexpected cachet to his publications.

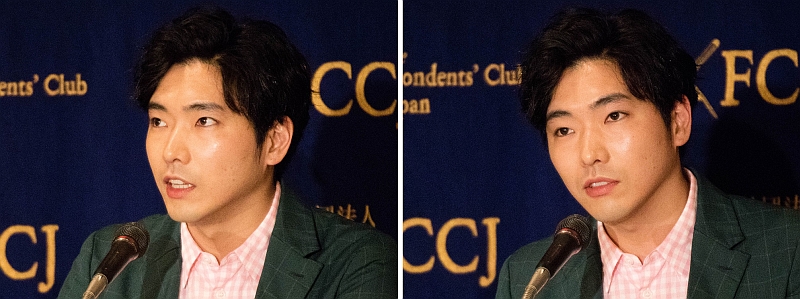

Both the director and his star saw a resemblance between Suei and Emoto, however unlikely that seems. ©Mance Thompson

But as Suei continued to press buttons and push boundaries, police scrutiny intensified. Called in regularly to be reminded just what was permissible in print (pubic hair, penetration and sex organs were absolute no-nos), he mastered the art of the repeated deep bow (“I apologize, but never regret”) and with “balls and stamina,” managed to stay in business and to capitalize on the zeitgeist (inadvertently inventing telekura phone sex clubs along the way).

Then one day, the freewheeling ‘80s were over, Suei’s magazines were banned and he lost millions of yen in bad investments. So he did what any bankrupt publisher would do: dressed up like his mother, called himself Gonzolo Suei, and began pitching “How to Win at Pachinko” guides on television.

Acclaimed actress Machiko Ono plays Suei's mother in the film.

© 2018 “Dynamite Graffiti” Film Partners

Suei, as we are amply reminded in Dynamite Graffiti, has a mother complex. “Some say art is an explosion,” he references Taro Okamoto early in the film. “In my case, my mom was an explosion.” He’s not being metaphoric. When he was a child in Okayama, Suei’s mother blew herself and her lover to bits with sticks of dynamite from the nearby coal mines. It is a defining moment that opens the film, and that the adult Suei (played with amiable and indelible charm by Tasuku Emoto), can’t get out of his mind.

In the film’s production notes, Tominaga explains: “In 1955, ten years after [Japan’s] nuclear explosion, a smaller explosion occurred in a mining village a hundred miles east of the Hiroshima epicenter, one that derailed the life of Akira Suei. He was young when his mother’s body was blown to bits. However, he was destined to be transformed by [it]. Had his mother not chosen to end her life in the grand finale of a lovers suicide pact by dynamite, the son may have grown to stay in the village and plow fields, or become a miner like his father, taking care of his aging mother as he builds a home with a wife and child; he may have even earned the respect of the village and become a member of the town council. Instead, he climbed to the peak of the erotic magazine industry.”

The smut peddler and the zealous cop (wonderfully played by Yutaka Matsushige)

consider where to censor New Self magazine. © 2018 “Dynamite Graffiti” Film Partners

During the Q&A session after FCCJ’s sneak preview of the film, Tominaga was asked just how much artistic license he took with Suei’s story. “I suppose I did take some,” he responded. “The film is based not only on his own autobiography, which goes by the same name as the film, but also on many other autobiographical essays he wrote. I also heard stories directly from Mr. Suei that were not included in any of his published writings, so I included some of them. I condensed those, to a certain degree, and created several composite characters. But there were so many interesting figures around Mr. Suei, I just had to include them. He was such a wonderful observer of those people, [he created] a really interesting reportage of those days. So I focused on the people who influenced him and who shunned him, taking about 100 characters and condensing them into 20.”

Asked whether he’d met Suei himself to prepare for the part, Emoto said, “I read the original [autobiography] when I knew they were interested in me. It just so happened that the cover has a photo of Mr. Suei, cross-dressing in his kimono, and I [agreed with the director] that it looked very much like me. That resemblance gave me some confidence to take on the role. I did meet Mr. Suei, and he was on set for about 6 days during shooting. He was watching the monitor, which was quite unnerving. I tried to observe him as much as possible when the cameras weren’t rolling, when he was talking with someone or standing there alone, gazing into the distance. I drew on those moments, on how he holds himself, to interpret how he is.”

Atsuko Maeda plays Suei's long-suffering wife. © 2018 “Dynamite Graffiti” Film Partners

Tominaga shoots 1960s – 1980s Tokyo in a de-glamorized style, capturing the rough-and-tumble excitement of Suei’s world. Asked why so many of the men in the film have fogged-up, taped-together glasses, Band-Aids on their faces and tangled hair, Tominaga explained, “That came from some hints in Mr. Suei’s work. He writes in detail about working in the red-light district, in the cabarets and so-called pink salons. He says that the cabaret managers, the girls who work there and the customers would always be in fights with each other. He writes about how many of them had injuries, scrapes and cuts and what-not. They weren’t well to do — these were people on the lower rungs of the ladder, what he called ‘survivors.’ I wanted to capture the survival mode that they were in through the details of how they look. I figured no one was going home with their clothes crisp and unstained. So I made their clothes dirty, their hair uncombed and their glasses smudged.”

©Koichi Mori

Was the charm a mirror of Suei’s own character, or rather Emoto’s own? Although he’s starred in several dozen films (including Tada’s Do-It-All House, We Were There, Piece of Cake, Gonin Saga, 64 and Reminiscence), few of his previous roles can be considered charismatic. “It wasn’t that I found [him] to be charming and tried to depict that,” laughed the actor. “I suppose it was the director who pulled that out of me. There’s an interesting dynamic between us, because I happen to be really feminine, and [Tominaga] is really masculine. He’s very determined and sure-handed when he directs, and that’s very manly. I found it comforting and let him lead the way. It was an enjoyable shoot, no stress on the set. I suppose that’s why I managed to depict the character in a charming way.”

With Dynamite Graffiti, Masanori Tominaga has fashioned a biopic that is at once a spirited, sprightly slice of the times and an ode to his subject’s self-made success through sheer hard work. Suei never stops working for long, putting in time at the drawing board in the wee hours, sometimes abetted by his long-suffering wife (Atsuko Maeda). The extra income may go toward various love affairs (a prominent one is with an employee who apparently contracts syphilis and goes crazy), or it may be to start up new magazines, it’s not made clear.

Gonzolo Suei touts her book on winning at pachinko. © 2018 “Dynamite Graffiti” Film Partners

Despite the often salacious subject matter of the film, like Shohei Imamura’s The Pornographers, it is heavy on double entendre and suggestion, but light on the actual sex act itself. Oh sure, there are scenes of women posing for Araki’s “ero-mantic” art photograpy, and endless shots of women in suggestive poses in the magazines. But in this age of #MeToo and #TimesUp, Dynamite Graffiti feels blessedly free of casual sexism and gratuitous smut.

© 2018 “Dynamite Graffiti” Film Partners

Posted by Karen Severns, Friday, March 16, 2018

Selected Media Exposure

- 柄本佑、エロ雑誌編集者を熱演「僕は内面が女子。男性的な監督に安心して抱かれていれば…」

- 「素敵なダイナマイトスキャンダル」柄本佑が「監督は男性的、僕は内面が女子」

- 柄本佑&冨永昌敬監督が登壇!映画『素敵なダイナマイトスキャンダル』日本外国特派員協会記者会見 レポート

- 柄本佑「僕は内面が女子」「素敵なダイナマイトスキャンダル」は冨永監督に「安心して抱かれた」

- ノンストレスな現場だった『素敵なダイナマイトスキャンダル』!

Read more

Published in: March

Tag: Akira Suei, Nobuyoshi Araki, Daido Moriyama, Genpei Akasegawa, New Self, Weekend Super, Shashin Jidai, Tasuku Emoto, Masanori

Tominaga, erotic publishing

Comments