At least three generations of Japanese have grown up wearing t-shirts emblazoned with the iconic image of Ernesto “Che” Guevara, the Argentinian physician, author and Marxist revolutionary. But few of them know about Guevara’s controversial exploits, and fewer still know that a Japanese- Bolivian fought with him — and died, as did Che, in a CIA-assisted ambush in Bolivia — 50 years ago this October.

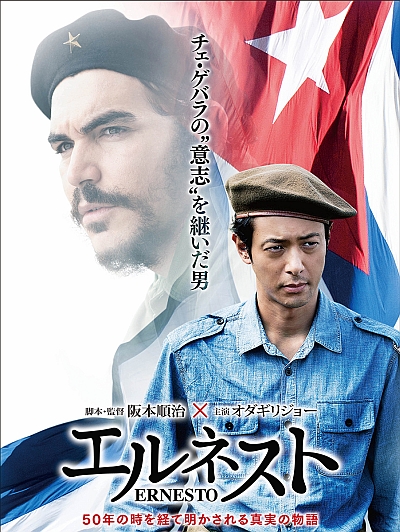

Junji Sakamoto’s new film, Ernesto, pays tribute to that man, Freddy Maemura Hurtado, a second-generation immigrant who became radicalized while in Cuba pursuing medical studies. Inspired by “The Samurai of the Revolution,” a novelized biography penned by Maemura’s sister Mary, Sakamoto has created a work that is at once Cold War history, coming-of-age story, compelling relationship drama and cautionary tale.

The project began when Sakamoto (The Projects, The Human Trust) came across the story of Maemura Hurtado, and was deeply impressed that he had followed his convictions so completely throughout his (tragically short) life. Realizing that he would do best to coproduce the film with a Cuban production company, thus gaining access to the island’s locations and local talent pool, he set about putting together the first Japan-Cuba coproduction since 1969 (not counting one documentary). Almost entirely in Spanish, the film is perfectly timed to mark the anniversaries of Che’s and Freddy’s deaths.

Sakamoto's films frequently feature scenes in languages other than Japanese, but this is the first

that is almost completely in another language. ©Mance Thompson, ©FCCJ (top right)

Ernesto opens with a historic 1959 scene, shot in Hiroshima. Just months after the Cuban Revolution resulted in the ousting of US-backed dictator Fulgencio Batista, Che Guevara (dead ringer Juan Miguel Valero Acosta) visits Japan in his role as a trade diplomat for the new communist government. Without notifying his hosts at the Foreign Ministry, he goes to the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park to pay his respects. Then he turns to a Japanese journalist (Kento Nagayama) who has followed him there. “Why aren’t you angry at the Americans?” he demands. “They have done such a horrendous thing to you.” It is a question that hangs heavily over the entire film.

During the Q&A session after the FCCJ screening, Sakamoto was first asked whether that visit had taken place, and why he’d included it in the film. “It’s a fact that Che Guevara visited Hiroshima and laid flowers at the Peace Memorial cenotaph,” responded the director. “It’s also a fact that Freddy went to Cuba for his medical studies, and not long after, the Cuban Missile Crisis began. I wanted to juxtapose these two events, and through them, to pose questions about nuclear warfare.”

He continued, “During the missile crisis, Che was probably the only one who had been to Hiroshima and had memories of what nuclear warfare could do. That must have been at the back of his mind.”

Che and Freddy in Cuba. ©2017 “ERNESTO” FILM PARTNERS

Following up, another audience member asked about the lines (quoted above) that Che speaks to the journalist, and how Sakamoto had balanced fact with fictional elements in the film. “That line actually came from the journalist who covered the event, who had been with Che Guevara on that day," responded the director. "All the lines in that scene are factual, and came from the journalist, who was the only one to cover his visit, since no one really knew who he was at the time. He has since passed away, but he made detailed notes about the visit. His family was kind enough to share them with me.”

Sakamoto went on, “I don’t think films should fictionalize events; they must be grounded in reality. We did a lot of interviews and research. I did take liberties as long as they were fact-based. Sometimes it’s necessary to take liberties in order to better depict the atmosphere or the spirit of the historical [time].”

Considering today’s constant North Korean missile "tests" and Donald Trump's chest-beating, did Sakamoto intend to play up the looming danger of war by delving into the complicated Cold War-era proxy wars in his screenplay?

Odagiri spent 4 months mastering his Spanish lines, as well as the correct body language. ©Mance Thompson

“The approach I took was to tell the story of one individual,” said Sakamoto. “There are, of course, Hollywood movies like 13 Days, that depict the Cuban Missile Crisis. But I wanted to depict this medical student who arrived in Cuba and experienced the crisis, but wasn’t ‘in the know.’ The students weren’t given a lot of information, and they were later angry that the US and Soviet Union had negotiated without [Cuban] involvement.”

Ernesto’s “one individual,” Freddy Maemura Hurtado, was born in Trinidad, Bolivia to a well-to-do Japanese father from Kagoshima Prefecture and a Bolivian mother, and he was determined from childhood to become a doctor so he could treat the poor. In 1962, Maemura (Joe Odagiri, nearly unrecognizable as a very studious young man) arrives in Fidel Castro’s Cuba to study not only medicine but also the “spirit of liberty and equality.” Yet classes are soon disrupted by the US naval blockade, and the school becomes a barracks for anti-aircraft artillery troops for the duration of the Cuban Missile Crisis. Maemura and his classmates are given the choice of enlisting in the fight against America’s presence, and the young physician’s radicalization begins.

Missile Crisis averted, Maemura continues his studies against the backdrop of the escalating Cold War, and is soon skillful enough to become a lab assistant. He shares his salary with Luisa, a fellow student whom his friend has impregnated but refused to help support, and life seems good. But when civil war breaks out in Bolivia following a US-backed military coup in 1964, he decides to slip back home and join Che Guevara’s revolutionary army there. He visits Che, a fellow physician-turned-rebel, to tell him that he is following Castro’s advice to “follow my heart” about becoming a fighter, rather than a doctor. The guerrilla commander bestows the nom de guerre "Ernesto Medico" on him. Two years later, their fates are forever entwined when deep-jungle ambushes by CIA-backed Bolivian troops capture the men and they are killed within weeks of each other.

Freddy listens to Castro speak at his medical school. ©2017 “ERNESTO” FILM PARTNERS

Odagiri (Bright Future, Over the Fence) disappears completely into the role of Freddy, aided by convincing makeup, and delivers a slow-burn, career-best performance. One of Japan’s tiny handful of truly international stars, he is surely the only Japanese actor who has tackled roles in every major language but Italian. Here, he speaks entirely in Bolivian-accented Spanish.

Admitting it was one of his most challenging to date, the actor responded to a question about preparing for the role: “Thank you for that question. I ’d wanted to have a drink before this press conference, but I refrained. I’m so glad I did, because I’m so ready to give a very serious answer. The way I approached the Spanish was not just to memorize the lines, but to be able to act in Spanish. For that, I sought the help of my [mostly Cuban] costars. I had three or four very kind costars who spent hours and hours with me, helping me mold this character.

“They each had their own visions of what Freddy would talk like in certain scenes, and they would read the dialogue for me. So I would ask them, ‘In this situation, how would he say this line?’ They showed me many possibilities, a full range of tones, and I then discussed different approaches to each scene with the director. With foreign languages, there are issues with [pronunciation], where to take a breath and the rhythm of the speech. It was all really complicated, and I’m so thankful to my costars, who I heavily relied on. Without their help, I wouldn’t have been able to make this character so well-defined.”

©FCCJ

Pointing out that Odagiri’s first lead, in Kiyoshi Kurosawa's Bright Future, ends with a scene in which aimless young men sporting matching Che Guevara t-shirts kick garbage along a Tokyo street, an audience member asked about the actor’s personal connection to Che. “I hadn’t thought about that last scene, thank you for reminding me,” Odagiri laughed. “When I decided to take this role, I told my circle of friends about it and they all said, ‘Are you playing Che?’ They probably didn’t think it was such an outrageous idea. One reason might be that I usually grow a beard and have unkempt hair. I do actually have a Che Guevara poster on my wall, and I have Che t-shirts, as well.”

Sakamoto had high praise for the film’s Cuban producers. “When we took this project to them,” he explained, “they said yes right away. We asked if there was any sensitivity with [a Japanese production] depicting this time period on film — since there are no Cuban films depicting this decade — and they kindly took it on as their own project, as well.”

For all its heavy political overtones, the director made it clear that the theme is one of commitment and optimism: “The name of the film, Ernesto, is not just Che Guevara’s name, it also has a meaning: someone who is very earnest… someone who has a goal and is adamant about obtaining it. I think that's an important message. Whether you’re involved in political activities or just going about your day-to-day life, it’s important to have a goal, and to have unwavering faith as you strive to achieve it.”

Freddy Maemura’s remains, which were missing until 1999, are now laid to rest alongside Guevara’s in Santa Clara, Cuba. Ernesto ends with footage of Maemura family members visiting the site, to thank Freddy for “inspiring millions of revolutionary doctors with your dream,” and becoming a role model for succeeding generations.

©2017 “ERNESTO” FILM PARTNERS

Posted by Karen Severns, Thursday, September 21, 2017

Selected Press Coverage

- エルネストとは”目的を決めた上での真剣”--主演オダギリジョー&阪本順治監督

- 「エルネスト」オダギリジョー、チェ・ゲバラを語る「部屋にポスター貼ってます」

- オダギリジョー、チェ・ゲバラとの縁に驚き「言われてみれば…」

- オダギリジョー、チェ・ゲバラとの“縁”に驚き 『エルネスト』記者会見

- オダギリジョー、全編スペイン語で挑んだ“もう一人のゲバラ”役「キューバの俳優に力を貸してもらって…」

- オダギリジョー「エルネスト」役づくりの質問に「お酒飲まなくて良かった」

- オダギリジョー、日本とキューバの合作主演映画「エルネスト」の会見に出席

- 『エルネスト』特派員協会会見と大使館試写

Selected TV Exposure

日本テレビ ZIP!SHOWBIZ TODAY オダギリジョー 異国の地で悪戦苦闘

Read more

Published in: September

Tag: Che Guevara, Junji Sakamoto, Cuban Missile Crisis, Joe Odagiri, Hiroshima, Bolivia