The Film Committee has been collaborating on annual special screening events with the Tokyo International Film Festival (TIFF) for a decade or more, but in this very challenging year, it feels more important than ever. TIFF announced last month that, barring catastrophe, it will hold a physical 33rd edition, with the implementation of strict health and safety measures, from October 31 – November 9 at theaters in Roppongi.

This in itself was a milestone, since many international festivals were forced to cancel due to the pandemic, and others were stymied by ongoing theater closures in their host cities. The most famous of canceled festivals was Cannes, which nevertheless announced a lineup of 'Cannes Premiere 2020' titles, a selection of films that it would have premiered at the festival, had one been held.

Among those titles was award-winning director Koji Fukada’s The Real Thing, a nearly 4-hour opus about a consummately dull salaryman whose life is overturned by an eccentric woman. Although Fukada was not able to appear in person, the film had its International premiere at the Pingyao Film Festival in mid-October, and will have its Japan premiere during TIFF, with the director and cast present.

©Koichi Mori

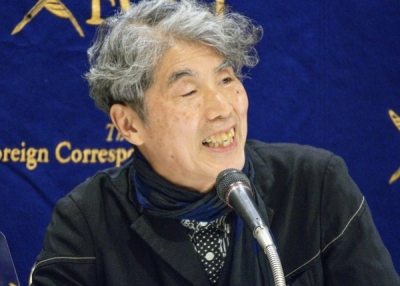

Fukada has been named the Japan Now Director in Focus for this year’s TIFF, and he joined TIFF Chairman Hiroyasu Ando and Selection Committee member Kohei Ando at FCCJ to discuss some of the highlights of the 33rd edition.

“There was a lot of deliberation as to whether to hold the festival this year, and whether it should be in a physical form,” admitted the chairman. “But we ultimately came to the decision that we would hold it physically so that we could bring audiences back to the cinemas. We want them to once again experience the joy of watching films on the big screen and to find hope for the future.”

TIFF will be screening over 100 films, with 32 of them (10 from Japan, 10 from the US/Europe and 12 from Asia) selected to receive the 'Tokyo Premiere 2020' label, making them eligible for the single prize that will be bestowed on films this year, an Audience Award chosen by all viewers.

©Koichi Mori

While conceding that there would be almost no foreign guests, from filmmaking teams to programmers to journalists (unless they are already in Japan), Ando emphasized that TIFF would be screening many world premieres as well as films drawn from the Berlin, Cannes and other festivals around the world, and that there would be virtual talks sessions with an array of international participants.

He also had this to say: “To represent what this year’s festival aims to achieve, we will be featuring the work of Koji Fukada in the Japan Now Section. We chose Mr. Fukada because he has been very active internationally, has made international co-productions and has an impressive filmography. Another reason that we hold him in high regard is that this year, he initiated the Mini-Theater Aid campaign in order to help support arthouse cinemas in Japan, who were struggling in the face of the pandemic.”

Kohei Ando (no relation), TIFF’s Japan Now programmer since the section was created 7 years ago and one of the members of TIFF’s new Selection Committee, shared his enthusiasm, while also invoking last year’s Japan Now Director in Focus: “Allow me to (first) quote from a great filmmaker that we recently lost, Nobuhiko Obayashi: ‘Films cannot change the past, but they do have the power to change the future.’

©FCCJ

“Mr. Fukada is a filmmaker who gives us deep insight into today’s Japan, and into the human condition, while urging us to contemplate the absurdities of society. We’re facing a very tumultuous year with the coronavirus pandemic; but with the perceptive work that Mr. Fukada has been producing, we look forward to seeing his vision of the future in the future.”

Asked how he felt about the Japan Now retrospective, which will showcase four of his feature films, including Cannes Jury Prizewinner Harmonium (2016) and a range of shorts from 2006-2020, Fukada had this to say: “It’s a real honor to be chosen as the Japan Now Director in Focus, and I thank the Tokyo International Film Festival for their brave decision.

“Exactly 10 years ago, I received the first major award of my career at TIFF and that was the springboard to launching my films into many other international film festivals, allowing us to secure distribution and reach overseas audiences as well as those in Japan. So this feels like a turning point, and I’ll take it as a sign of encouragement to continue making films."

©Koichi Mori

The first question from the assembled press was an obvious one: “Why did you call your selection a ‘brave decision?’”

Fukada laughed. “I chose the word because, first and foremost, I’m a rather young director and I don’t have that many films in my filmography yet. Also, I don’t make commercial films. I do think one of the functions of a film festival, perhaps its ‘social responsibility,’ is to shine a spotlight on filmmakers whom we haven’t [passed judgment on] yet, to highlight a particular artistic vision or a type of auteurism. In terms of fulfilling that responsibility, I appreciate TIFF’s bravery.”

Although this was not mentioned, Fukada plays a uniquely activist role in the Japanese film industry, and the Mini-Theater Aid crowdfunding campaign is just one manifestation of it. In 2012, he was one of the founders of the Independent Cinema Guild, a support group for all practitioners in the field — from filmmakers and festival organizers to cinema owners and film critics — to correct the “serious imbalance in the diversity of films being produced in this country” and to stop the “cultural impoverishment,” as well as actual impoverishment, of indie filmmakers who work with insanely low budgets.

©Koichi Mori

In 2019, when issues of sexual and power harassment in the film industry started making headlines, Fukada spoke out in support of public dialogue, and he has stayed in the headlines with his candid criticisms of an industry that is built on constant manga, novel and TV-show adaptations, and his pleas for more government subsidies to support culture. Just last month, in an interview with AFP, he said, “It's difficult to produce non-commercial films in Japan, where a lot of importance is given to their marketability… At this rate, Japanese cinema is going to go down the drain.”

Asked whether he thought there would be significant changes in the industry as a result of Covid-19, Fukada said that there was now “an extra layer of security precautions that have to be implemented on set. We were probably not taking stringent enough precautions prior to the pandemic, because we work within very small budgets and that limits the amount of time we have on set. Now that we have to fight the pandemic, it means we need a larger budget to increase the manpower required on set. We need to create a support system within the industry, and hopefully, be able to rely on some government funding to do so.”

©Koichi Mori

Outside of the Japan Now section, TIFF will be showing over 3 dozen more Japanese titles, including many animated films, remastered classics, upcoming commercial releases and new work by emerging directors. Kohei Ando recommended several Japanese titles before commenting, “The European and Asian films in in this year’s Tokyo Premiere 2020 selection focus heavily on race, immigration, minority and gender issues. I wish that more Japanese filmmakers would delve into societal themes — but this does not apply to Mr. Fukada’s work, of course.”

TIFF’s chairman noted that there was likely to be much discussion of such issues during the nightly Asia Lounge Conversation Series, a new initiative proposed (and sometimes moderated) by Palme d’Or winner Hirokazu Kore-eda. “Although it will be online only,” explained Ando, “we will be pairing up various filmmakers and film industry leaders from throughout Asia, with prominent Japanese industry figures.”

©Tokyo International Film Festival

Following the panel, the audience was treated to a special screening of Fukada’s award-winning 2019 film, A Girl Missing, and a Q&A session with Fukada that lasted another 50 minutes. There were questions on topics ranging from cinematography, casting and poster art to the state of indie film industry in general — and the director would have welcomed many more if closing time hadn't arrived.

Tsutsui (front) and Ichikawa (back) in an image from A Girl Missing.

©2019 YOKOGAO FILM PARTNERS & COMME DES CINEMAS

For the film, Fukada reunited with the inimitable star of his Cannes award-winner Harmonium, Mariko Tsutsui, for a layered story about a woman whose kindness is ruthlessly crushed following a scandal in which she’s an innocent bystander. Tsutsui brilliantly plays Ichiko, a devoted home hospice nurse to the cancer-stricken matriarch of the Oishi family, and surrogate mother to her two granddaughters, Motoko (Mikako Ichikawa, equally superb) and Saki, whom she helps study for their exams. Ichiko is preparing to marry again, to a doctor whose young son clearly adores her. All is well until Saki goes missing and Ichiko’s nephew is implicated in the crime. At Motoko’s urging, she says nothing about the connection to the police. But before the guilt can start consuming her, her relationship to the culprit goes public and the press makes her life a living hell.

A master of the family-crisis genre, Fukada ratchets up the suspense and the ambiguities in A Girl Missing, creating a double-strand narrative of incredible chronological complexity that rewards viewer vigilance and packs a deep emotional punch.

©FCCJ

“I offered Ms. Tsutsui the part even before I started writing the script, and she accepted,” the director explained. “It was wonderful for me because I know that she’s extremely skilled and there’s nothing she can't do, so I wrote it [without compromises].”

One audience member, a professed fan of Fukada’s work, apologized for “being rude” but noted that she’d found the character of Ichiko to be “even more repulsive than the criminal in Harmonium. I was fascinated with her but I didn’t like her at all.”

Fukada nodded. “People often come to me and say they can’t empathize with this or that character of mine. I wonder whether it’s really necessary to be able to empathize? As someone who’s been an ardent filmgoer for years, I must say that I’ve never made the protagonist’s likability a factor in my decision about whether or not I like a film.

“Actually, I’m more excited by a character that I can’t understand or can’t relate to. I think a character we can’t understand reflects reality more closely than otherwise. I think it’s hard to really understand someone else. You can guess, but you can never really know — not even with yourself.”

A Japanese film critic, noting that the film had opened in August in France, where it had become a big hit and played in more theaters than Takeshi Kitano’s films ever did (Kitano was once hugely popular there), asked why the reception had been so different from at home.

Nodded Fukada, “It opened in 119 theaters and expanded to 200 theaters, becoming what they called a ‘smash hit.’ I think that is probably at least partially the result of the pandemic, since not too many films were opening. But my previous film, Harmonium, actually drew a much larger crowd in France than in Japan. It’s not that my name is better known in France, so they’re not coming to see it because it’s a ‘Fukada film.’ I’m not a commercially successful director like Mr. Kitano or Mr. Kore-eda, I don’t make entertainment pieces, my films are rather dark. But I think the cultural backdrop allows for more cinematic diversity there.”

The North American and Japanese film posters. ©2020 Film Movement;

The North American and Japanese film posters. ©2020 Film Movement;

© 2019 YOKOGAO FILM PARTNERS & COMME DES CINEMAS

Marveling that children are taught about cinema from an early age in France — “they’re even shown Yasujiro Ozu films in grade school!” — Fukada continued, “They grow up watching films, and they have a wider range of tastes when it comes to art and cinema. It also allows for diversity and openness toward different cultures. I think this is something Japan could benefit from doing. Perhaps we should start including film education in our classrooms. If we do that now, more people in this country might come to see my films 20 years from now.”

Fukada was asked why the Japanese and English titles were so very different. “I had decided on the Japanese title, Yokogao (meaning profile), early on,” he responded, “because I thought Mariko Tsutsui’s profile was really striking. It was also a good metaphor for the story, because we can only see one side of ourselves (the front). My international sales company, MK2, came up with the English title, which is quite nice because it has a double meaning. They wanted it to sound like a suspense film, which it is, and also to indicate that the girl who’s missing is the protagonist herself. The French title is L’Infermiere, meaning caregiver. So the titles are all different and so are the posters.”

Ichiko is confronted by a rabid press. ©2019 YOKOGAO FILM PARTNERS & COMME DES CINEMAS

Taking the French theme even further, another critic asked about Fukada’s experience getting funding in Japan vs. in France (the National Centre for Cinema and the Moving Image or CNC supported both A Girl Missing and Harmonium). Admitting that he could address the subject for the next 2 hours, the director said, “I would say that independent filmmakers in Japan are in dire straits in three respects: first, they don’t receive the same level of funding, in terms of either the budget or the percentage of government subsidies that go to culture and film. The arts subsidies from Bunkacho (the Agency for Cultural Affairs) are ¥200 million, while in Korea, KOFIC contributes ¥4 billion and in France, CNC contributes ¥8 billion. Japanese are getting only 1/9 of what Korean filmmakers get, and 1/8 of what French filmmakers can expect. In the US, where there aren’t a lot of government subsidies, at least there’s a lot of private financing from individuals and companies.

©Koichi Mori

“Second, in Japan, about 80% of box office revenues go to big studios and corporations, because it’s still legal here for them to also own the distribution chains.

“Third, what also helps filmmakers in France and Korea is that a tax is imposed on each ticket sale — in France 10%, Korea 3% — and that tax money is pooled and redistributed to the film industry. The CNC and Korea’s KOFIC push for the further development of film culture as well as diversity in filmmaking. Here, there’s simply no systematic way that the industry is able to come together, regardless of whether they’re major studios or indie filmmakers.”

But despite the depressing state of the industry, the delays in shooting his new script, and major lifestyle changes imposed by Covid, Fukada’s mood was upbeat. After all, the Tokyo International Film Festival will be holding a physical edition, and Fukada will be appearing for live Q&As after each of his films is screened, along with key cast members.

There is also this to look forward to: Mariko Tsutsui has been nominated as Best Actress for her exception performance in A Girl Missing at the 14th Asian Film Awards, and the winners will be announced on October 28.

©FCCJ

- 深田晃司が語るこれからの映画制作とは?東京国際映画祭の記者会見に登場

- 深田晃司監督「本当に光栄。英断に感謝」 東京国際映画祭の「Japan Now部門」で特集

- 深田晃司監督、コロナ禍より映画予算の低下に不安感「助成金の少なさは安全対策にも影響」

- 深田晃司監督が強調する映画祭の役割「評価が定まらない才能に光を当てること」

- 「商業映画とは違った基準で、新たな才能に光を当てることも大切」。深田晃司監督日本外国特派員協会 記者会見

- 東京国際映画祭は「評価の定まっていない人にスポット」と深田晃司 監督|Japan Now部門二〇二〇

- 韓国の9分の1、フランスの8分の1… 日本映画に対する文化予算の現状、構造問題を深田晃司監督が憂慮

- 第33回東京国際映画祭「Japan Now部門」深田晃司登壇 日本外国特派員協会記者会見

- “TIFFの申し子”深田監督が映画祭に込めた想いとは?「Japan Now部門」特集 気鋭の表現者 深田晃司 日本外国特派員協会 記者会見レポート