For over 20 years, journalist-cum-filmmaker Zhongyi Ban has relentlessly documented the forgotten women who were forced into sexual servitude by the Japanese army during World War II. Returning to his homeland each year from Japan, where’s he been resident since the early 1990s, Ban tracked down over 80 women, recorded their stories, viewed the scars of the atrocities inflicted on them, and even collected money from sympathetic Japanese to cover their medical and other costs.

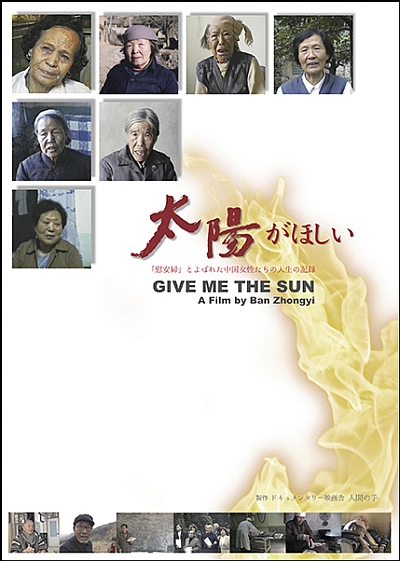

After several books and prior films on the issue, he has now completed Give Me the Sun, the most comprehensive and compelling portrait of Chinese comfort women yet. Presenting a specially edited version of the film, with English subtitles and narration, at FCCJ, Ban noted, “ This film was made with the support of individuals in Japan. Some 730 people contributed to its production, including Roger Pulvers and John Junkerman [both present on the dais]. It took a year and a half to complete, and we’ve been screening the [longer, Japanese version] at least once a week around the country since then — in halls, not yet in theaters — due to the enthusiasm of people to show the film.” He did admit, however, that, “There are a lot of people who disagree with films like this, so it’s quite possible that, down the road, we may receive some backlash from them. So we’re vigilant.”

Pulvers, a noted author, playwright and screenwriter who narrated the film, commented, “My role in this has been very small over these past many years, but it’s been an honor to play even a small part in [Ban’s] immense contribution to history, journalism and the art of film. I think one of the old ladies in the film said something very telling when she remarked that the Chinese government doesn’t want this story to get out either. When you have the collusion — whether it’s a coincidence or not, I don’t know — of the two most powerful countries in Asia, and you have somebody with the courage of [Ban], I am just awed and impressed.”

Junkerman (left) and Pulvers (right) have worked with Ban on his previous films.

Ban’s mission to locate and document the women began after Japan’s first conference on war reparations in 1992 revealed just how widespread the comfort station practice had been. But as late as 1996, only one Chinese comfort woman had publicly identified herself, due to their fear of what Ban terms “political harassment” and of being charged with “enemy collaboration.”

Give Me the Sun (a reference to the squalid, dark conditions in which the women were held) introduces us to a group of seven aging Chinese women whose bodies and minds were irrevocably scarred by the unspeakable brutality they suffered during World War II, when they were often gang-raped for months until their families could ransom them. Some were lured into sexual slavery by locals working for the Japanese Army, who promised them work in factories or hospitals; others were simply abducted and enslaved in the nearest comfort stations.

Chinese scholars have estimated that close to 100,000 women were forcibly taken from their homes during the war, although lack of official documentation has made it difficult for historians to reach an agreement on the exact figure. The women in Ban’s film were among the measly one-quarter of such victims who actually survived the war. Give Me the Sun retraces the contentious history of the issue and strengthens the women’s heart-breaking accusations by including interviews with a handful of former Japanese soldiers, from an infantryman to a company commander, as well as Chinese recruiters and Japanese comfort women.

©Koichi Mori

But Ban admitted that this third film on the issue was prompted mostly by “former Osaka Mayor Toru Hashimoto’s declaration, right here at the Foreign Correspondents’ Club [in May 2013], when he essentially denied the existence of comfort women, calling them prostitutes, as well as the bashing of the Asahi newspaper for their reporting on the comfort women issue. This brought the issue to the attention of the Japanese public, but most of the attention was paid to the South Korean comfort women. Far less is known about the Chinese victims of sexual violence, so I wanted to get exposure for those women. I put out a call for support to make the film, and I immediately got it from people of conscience and justice-seekers in Japan.”

South Korean comfort women have been increasingly in the headlines since December 2015, when Japan agreed to set up a fund to indirectly compensate the victims, but only if there is no further mention of the issue. The “diplomatic deceit,” as one critic termed it, has resulted in continued and widespread protests — as well as to Japan’s nonpayment until certain conditions are met.

Chinese comfort women have been largely ignored in the ongoing war reparations dialogue, primarily due, says one scholar, to China’s ongoing “censorship, dictatorship and disregard for human rights,” and the postwar government’s priority to reconcile with Japan at the expense of all else.

©Koichi Mori (left)

Ban visited one of the shared care-homes for comfort women in South Korea, and was impressed by the level of physical, psychological and financial support they received. “In China, on the other hand, these women are living in deep poverty, without any support whatsoever from the government or from Chinese society. Of course China is not a democracy, so it’s not easy for the public to take action.”

To a question concerning the differing circumstances between the South Korean and Chinese victims, Ban noted that, since Korea had been a Japanese colony, “Korean women were seized or recruited and sent to various parts of Asia where Japanese troops were stationed. They were put into established comfort stations, where they were treated as objects and sexually violated.” Of the 80 women Ban had tracked down in China, including 20 Koreans who had been held captive on the border with Russia, “[typically], Japanese troops stationed out in the provinces would seize women from nearby and put them into rooms where they were kept as sexual slaves. Almost none of them had experience in a comfort station. So we can’t really call them ‘comfort women,’ but rather, they were sexual slaves.”

Ban with the English poster for his film.

In 1996, lawsuits for reparations were filed in Japan by four of the women in Give Me the Sun, and in 1998, by 10 more, with the aid of Japanese lawyers. All the suits were dismissed or lost in 2000. “Why did I lose the lawsuit? Where is the truth?” wails one of the victims. “ Why doesn’t the Japanese government apologize and compensate?” In the film’s closing moments, shortly before she dies, she vows to become a demon, so she can continue her fight for justice.

“Many of them have died, and others are in the last years of their lives,” Ban emphasized. “But it’s not too late to wish that they could receive better treatment during their final years… They’re desperately poor and desperately need assistance for their medical care. But if they were given a big chunk of money, they wouldn’t know what to do with it. That’s not what they’re after. They’re after a sincere, heartfelt apology.”

Ban remains hopeful that there can be “an investigation into the historical reality of the comfort women situation, and research and education on the issue.” His heroic devotion has earned many admirers, as well as detractors. “Ban has told me over the years that he has enemies on both sides,” said Pulvers, “— that the Chinese and the Japanese are against him in many ways. But I firmly believe that the day will come that he will be rewarded by both sides, given honors by both sides, for this most remarkable work.”

— Photos by FCCJ except where noted.

Human-hans/ Ban Zhongyi ©2016

Posted by Karen Severns, Sunday, May 08, 2016

Read more

Published in: May

Tag: comfort women, WWII, war reparations, documentary

Comments