“In the political context of Japan today, the question really is, how much can a film accomplish?”

That was the Socratic response given by producer Mitsunobu Kawamura when he was asked why he had produced not one, but two films featuring the same woman in 2019.

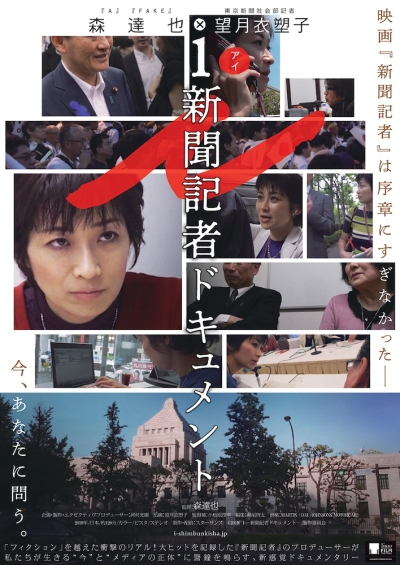

The woman in question, crusading reporter Isoko Mochizuki, is the star of political thriller The Journalist — although she’s played by an actress and the role has been heavily fictionalized — and she is also the firecracker at the heart of i: Documentary of the Journalist, which follows the real-life Mochizuki so closely, she is barely absent from the screen.

Mochizuki questions a government rep. ©Star Sands,Inc.

Kawamura, speaking to an overflow crowd at FCCJ following the screening of the documentary, admitted, “I hadn’t anticipated making both a documentary and a narrative film when we started. I think this is the first time in history that it’s been done. We actually had a different focus at first, but then a number of incidents took place in rapid succession that really should have brought down the Japanese government. The most film-worthy of these incidents was the rape case of Shiori Ito. But she was in a very difficult, delicate situation, and it was around that time that Ms. Mochizuki’s book ‘The Journalist’ came out, so we shifted our focus to her.”

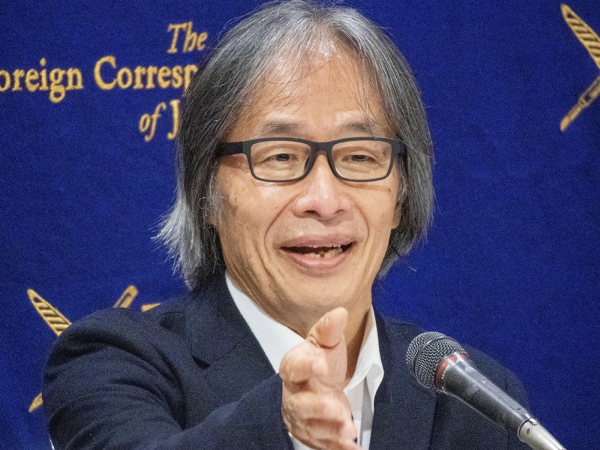

Tatsuya Mori, the renowned director of such controversial films as A, A2, 311, Fake and now, i: Documentary of the Journalist, explained that he’d been working on his first narrative feature project when Kawamura hired him to direct a fictionalized version of Mochizuki’s book. When the producer then asked whether he could also direct a documentary about Mochizuki, Mori stepped down from the fiction feature to focus on the documentary.

Kawamura (left) and Mori fielded a range of questions, many of them not what the producer, at least, was expecting. ©FCCJ

In June, The Journalist became a surprise hit in Japan. And less than a week before their appearance at FCCJ, Kawamura and Mori’s documentary won the Best Film Award in the Tokyo International Film Festival's Japanese Splash section, bringing them far greater instant attention than either had anticipated.

Although i: Documentary of the Journalist doesn’t mention Japan’s ranking on the 2019 World Press Freedom Index (it’s a very low 67; the US is at 48), its traditional media have earned increasing criticism for their herd mentality, for acting “more as stenographers than inquisitors,” as Motoko Rich recently put it in The New York Times, and for obediently following the dictates of their kisha clubs, which extend membership only to specific news organizations, allowing them exclusive rights to cover specific government offices with the expectation that questions will not be probing.

Mori and Mochizuki chat during a break from filming, which took place from December 2018 until October. ©Star Sands,Inc.

That makes Mochizuki, a reporter for Tokyo’s largest regional paper, The Tokyo Shimbun, a notable exception. She has defied the dominant media culture and waged a lonely battle for the truth, becoming something of a press freedom folk hero for her prickly interactions with government officials, particularly at the Cabinet Office briefings that have helped make her (in)famous.

i: Documentary of the Journalist thrusts the viewer into Mochizuki’s daily life as she travels around Japan with her maroon roller luggage, chasing some of the biggest stories of the past year — from the ongoing disputes over US base re-siting in Henoko, Okinawa, to the initial dismissal of reporter Shiori Ito’s charge that she’d been sexually assaulted by a colleague with close ties to the Abe Cabinet, to the Morimoto Gakuen and Kake Gakuen school scandals implicating the prime minister and his wife — and relentlessly peppering officials with questions in her quest to get behind their smokescreens.

©Koichi Mori

“What are you hiding?” she asks them. “It’s unethical to dodge scrutiny. You’re in charge, be responsible! What you’re doing is shameful.” It’s no wonder that, although her paper receives mostly supportive emails about her behaviour, there have also been death threats.

Mochizuki was publicly censured by the Cabinet Office earlier this year, and to the government’s surprise, hundreds of supporters turned up at the prime minister’s office, rallying on her behalf and pressing for greater transparency at the highest levels. “Isoko Mochizuki is me! Isoko Mochizuki is all of us! Fight for the truth!” roars the crowd in the film, as the journalist herself watches from the sidelines in amazement.

©Koichi Mori

There is an important message in the small ‘i’ of the film’s title, and it’s spelled out in text on the screen: “Don’t be ‘we.’ Be ‘I.’ First-person singular.” Mori was asked why he seems to be advocating for a more independent populace, when Japan is so famously consensus-minded.

He responded, “Human beings in the West as well as the East are group oriented. Because of groups, we have created wonderful cultures around the world. But there are side-effects: everyone moves in the same direction, like a school of fish. This leads humanity to make mistakes. ‘We’ is definitely important, but ‘I’ is also important. I believe that ‘I’ is too weak. I think we need to strengthen the ‘I’ in Japan.”

Mochizuki at work in the Tokyo Shimbun newsroom. ©Star Sands,Inc.

Asked why Mochizuki seems to have a much stronger ‘I’ than ‘we,’ Kawamura purposely deployed two controversial Japanese expressions that have making headlines. “Ms. Mochizuki is really KY — kuuki yomenai,” he explained. “She’s oblivious to the surrounding atmosphere. And she doesn’t do sontaku — she doesn’t brown-nose (by anticipating and fulfilling superiors’ needs). In making this film, it occurred to me that the intense peer pressure that exists here is bringing Japan to a state of crisis, and really represents a danger to society.”

Have a century ago, esteemed journalist Edward R. Murrow warned, “A nation of sheep will beget a government of wolves. ” As governments around the world continue oiling their misinformation machines, denying the public’s right to know, and waging war on the media’s “fake news,” Mori has understandably stepped up his advocacy of media’s all-important watchdog role. A professor of media literacy at Meiji University, he is also the author of over 30 best-selling books on social issues and the media, and winner of the Kodansha prize for nonfiction.

©Koichi Mori

He recalled that when he’d approached the Aum Shinrikyo cult to request their permission to shoot the documentary A,which would earn him international acclaim upon its release in 1988, he was surprised to discover that no one else had bothered to even ask.

“OK, so here’s the quiz,” he told the audience. “Does that make me special? No, not at all. What I’m doing is what everybody should be doing. I only appear to be special because of the deteriorating standards of others. Ms. Mochizuki is the same. If she doesn’t get an answer the first time she asks a question, she asks again. If she still doesn’t get an answer, she goes and conducts firsthand research. She’s doing the job of a journalist. She only appears to be special because of the sinking standards of those around her.”

©Koichi Mori

He continued, “The Japanese media is in terrible shape these days, but is that because they’re wrong-headed or weak? The media and Japanese society function together, and reflect upon each other. The reason the media is weak is because the public is weak. We elect third-class politicians because we are third-class citizens. We’ve got to find a way out of this dynamic, this mutual reinforcement. We’ve got to find a way to improve the situation overall.”

Asked whether Mochizuki’s example might inspire others, the director said, “It’s difficult. But as long as people have the feeling that the status quo is not desirable, there’s a possibility of change, whether they see these two films or not, whether they’re directly influenced by Ms. Mochizuki or not. As long as there’s a sense that things cannot continue the way they are now, it’s possible. There are many people in the media who are working very hard and have a strong sense of responsibility. If those people act on their sense of responsibility, then there’s a possibility for dramatic change to take place within the media.”

He waited a beat before adding, “Or alternatively, if 10 million people watch this film, then society will change overnight.”

The filmmakers with the Japanese poster for the documentary. ©︎FCCJ

Kawamura was slightly more upbeat, despite rumors that the Japanese Agency for Cultural Affairs had pulled promised funding from another film he produced in 2019, Miyamoto, as punishment for his focus on Mochizuki. “Portraying a woman who fights on a daily basis at the prime minister’s office gave me great encouragement and strength in the course of making the film,” he told the audience. “I think [her approach] is something that’s very much needed… As a producer, my takeaway is that there’s nothing to be afraid of. It appears that there’s social pressure and that there’s a formidable force acting against us, but in fact, that’s a phantom. There’s no real danger in doing what we’re doing.”

As soon as Mori finishes adjusting the English subtitles to accommodate his final cut (he re-edited the film slightly after the TIFF world premiere, re-recording his narration in a more “relaxed way,” making the animation more “fantastic,” and changing the placement of the music), i: Documentary of the Journalist will begin making its international festival rounds. The good news for Japan-based viewers is that Shibuya’s Eurospace theater intends to screen the English-subtitled version.

Let the 10-million-viewers challenge commence.

©Star Sands,Inc.

Posted by Karen Severns, Thursday, November 14, 2019

Selected Media Exposure

- Review: i: Documentary of the Journalist

- UNE DÉCENNIE QUI S’ÉTIRE À/VERS SA FIN

- 森達也が日本のジャーナリズムに言及「劇的に変わる可能性はまだ残されている」

- “日本はまだ劇的に変われる可能性はある”森達也監督、“相手は政治権力ではなくて、同調圧力 ”河村光庸P-東京国際映画祭 日本映画スプラッシュ部門作品賞『i-新聞記者ドキュメント-』

- 権力の横暴とマスコミの閉塞 記録映画「i-新聞記者ドキュメント」 森達也監督に聞く

Read more

Published in: November

Tag: Tatsuya Mori, Mitsunobu Kawamura, Isoko Mochizuki, Abe administration, Moritomo Gakuen, Kake Gakuen, Shiori

Ito, Henoko, US bases in Okinawa, awardwinning, documentary

Comments