Japan comes in for a fair share of head-scratching over its “English” retitling of foreign films (personal favorites: New York Style Happy Therapy for Anger Management; Wild Speed for The Fast and the Furious).

But what happens when a director must decide on the English name of a film that is rather colorfully titled (read: potentially offensive) in Japanese? That was the dilemma facing Hiroshi Okuyama in 2018.

As the young filmmaker explained during the Q&A session following FCCJ's screening of his heralded feature debut, Jesus, “I had originally thought about calling it I Hate Jesus, a direct transliteration of the Japanese. But when it was selected for the San Sebastian International Film Festival, I was asked to reconsider. I got advice from a lot of people, and I realized that it was drastically different from the nuance of the Japanese title [Boku wa Iesusama ga Kirai].

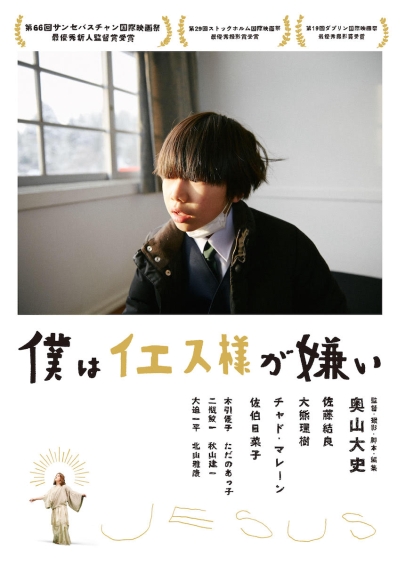

Chad Mullane, playing the eponymous character, triggers giggles. ©Koichi Mori

“First of all, boku is not the same as I. And Iesusama, or Jesus-sama, is very respectful, which is also not translatable. So the title I Hate Jesus sounded too rock-n-roll, according to some people. Also, I think there’s a different approach to titling films in Japan. With international films, it seems they [often] hone it down to a single word, which leaves the director’s intention up to the audience’s imagination. With Japanese titles, there ’s a lot of explaining beforehand. So those differences in approach resulted in the difference between the Japanese and English titles of this film.”

We’ll never know whether his choice had an impact on the film’s fate, but Jesus propelled Okuyama to the New Directors Award at San Sebastian, making him the youngest recipient of the prize and making the film an instant Must Watch. It went on to garner further awards and acclaim at other international festivals, assuring that the emerging writer-director-cinematographer-editor will be on every programmers’ radar with his follow- up effort.

Asked whether he felt the festivals had been a good way to foment interest, Okuyama demurred, saying he didn't yet have enough experience to know. But he added, “As an independent filmmaker... you really have to think about how to commercialize your film, how to get as many people as possible to see it. I think entering international film festivals is one way to do that, and it’s better to do it than not to do it.”

Saeki, Okuyama, Mullane ©︎FCCJ

He recalled, “I didn’t have any qualms about having a religious figure like Jesus in my film when it came to Japanese audiences. But when it came to the audiences at San Sebastian, the anxiety set in. There’s this huge statue of Jesus Christ above the town, and I was really worried at first. But ultimately, the audience seemed to receive the film very well. They were able to read enough meaning into the film that they could understand the Jesus figure as both a symbol of the protagonist’s belief and as his imaginary friend.”

Suffused with a nostalgic glow and told entirely through the eyes of its 11-year-old protagonist Yura, Jesus is so gentle, so modest, that the international accolades may seem excessive on first viewing. But the story sticks long after one leaves the theater.

Yura in his new smalltown classroom. ©︎2019 Heikai Sengen

As the film opens, Yura (Yura Sato) and his parents are leaving Tokyo for a snowy town in Gunma following his grandfather’s death. Moving in temporarily with his grandmother Fumi (Akko Tadano), the introverted young boy attempts to fit into his new environment. Arriving at his new school, he is surprised when his classmates run off to “worship” after roll call. A helpful teacher loans him a bible and escorts him to the chapel, where a sermon is delivered, a prayer recited and hymns sung.

Completely unfamiliar with the Christian catechism, Yura proves to be a fast learner. One morning during the Lord’s Prayer, Jesus himself (Chad Mullane) appears before him — apparently invisible to everyone else — and silently communicates “Ask and ye shall receive.” So Yura begins to ask, and when his wishes are granted, to have faith in His power.

By divine intervention, he even becomes best friends with the most popular boy in the school, Kazuma (Riki Okuma), who loves soccer and has a gorgeous, giggly mom (Hinako Saeki).

Kazuma and Yura ©2019 Heikai Sengen

Everything is wonderful until tragedy strikes, and Yura is faced with a full-blown crisis of faith.

Jesus is filled with delightful surprises and oddball moments and its snowy setting is shot with breathtaking beauty (by Okuyama himself, who also edited the film). There is also an autobiographical dimension to the story (an important dedication appears in the end credits that suddenly puts things into perspective).

Prompted to tell the audience more about that, Okuyama explained, “I did have the experience of losing a friend when I was just about the same age as Yura, in 5th grade. I remember the teacher coming to me and saying, ‘Let’s pray together.’ I was really puzzled by that, to tell you the truth. So I always had in mind that, if I were to make a film based on my own experience, this was one of the things I wanted to depict.”

While the film is anchored in reality, Okuyama’s singular approach to depicting Jesus elevates it to art.

Mullane indicates where he will be taking confessions. ©Koichi Mori

Mullane, who appeared at FCCJ in full Christlike regalia, from the robes of flax to the crown of thorns, stayed in character throughout the Q&A session, regularly cracking up the Japanese press. Although he’d had no lines in the film, his silent antics therein — from ascending upward with arms spread to hanging out with Yura as he takes a bath — spoke reams about the character. Mullane, an Australian-born comedian who’s a member of the Yoshimoto comedy empire, was no less goofy in person.

“Hello,” he introduced himself to FCCJ’s crowd in Japanese. “I am Jesus Christ. I have come from Gotanda, my second hometown, by train, where everyone was praying to me. I would like to extend an offer to hear your confessions tonight. If you’re interested in confessing, please see me later.”

When Okuyama was asked about the subtitles, which were done by Mullane, the director responded, “I didn’t give him much guidance. But one thing that really impressed me was how meticulous he was regarding which Christian denomination the [characters] were members of, since that would affect the sacred verses they were reciting. I think that was one of the reasons it was so well received among international audiences.”

Yura celebrates Christmas with Kazuma and his mother. ©︎2019 Heikai Sengen

Mullane chimed in: “Apparently we had a barter agreement. If I wanted to appear in the film, I had to do the subtitles.”

Protested Okuyama, “Let me set the story straight: we cast Chad before long before thinking about subtitling the film. It was only later that I discovered Chad also did subtitles. There was no barter.”

When Okuyama was asked about the subtitles, which were done by Mullane, the director responded, “I didn’t give him much guidance. But one thing that really impressed me was how meticulous he was regarding which Christian denomination the [characters] were members of, since that would affect the sacred verses they were reciting. I think that was one of the reasons it was so well received among international audiences.”

“There are many truths,” quipped Mullane.

Saeki ©︎Koichi Mori

Asked about casting Hinako Saeki, known for her roles in horror films, as Kazuma’s mother, Okuyama said, “I’d seen her in films in the past, and I felt she had the qualities I was looking for, especially for the final scene. It ’s a devastating scene, and she had to be as devastating as she was in it, because that’s the completion of the protagonist’s character arc, where he parts way with Jesus. So it had to be a strong moment and she had to be a strong character.”

Recalled Saeki, “The first time I read the script, I was thoroughly impressed. I actually cried three times while reading it. I honestly didn’t know why the director came to me for the role, but I was so honored and so happy to be part of the film.”

And the casting of the eponymous role? “I had Chad in mind from the get-go,” Okuyama said. “I’d already decided on him even before I had the script. I only had the [plot outline], so I couldn’t even give a script to him. I’d seen him on TV, and what I liked about him is that he sometimes has this expression that makes him look like a few screws are loose.”

©Koichi Mori

Before Mullane could fashion a retort, he was asked whether he’s Christian himself. “I died and was resurrected, so I suppose I must be a Buddhist,” he responded, coyly.

Did he have any fears or trepidation about taking the role, portraying a Christ figure the likes of which the world has not seen? “I was a bit worried about being a punchline,” admitted Mullane. “But referring to the bathtub scene, it wasn’t me who parted the waters. And [referring to a scene of sumo wrestling] sumo is almost a religious sport in Japan. I do think the director was the most God-like figure on the set.”

Okuyama was asked about his relationship to faith today, so many years after it had been shaken. “I do believe in Jesus Christ and I do believe in Christianity,” he said. “Why did I then make a film called I Hate Jesus Christ? I had an interesting experience at the Macao International Film Festival. There was an audience member who was Christian but very excited about the film, so I asked him what he thought about that title. He said he thought that hating something means that you believe in it. So I realized that’s [the way I feel], and I do believe.”

In a film of only 76 minutes, Hiroshi Okuyama has created a world that feels not only true to life, but also otherworldly.

Yura and the school minister. ©︎2019 Heikai Sengen

When a journalist asked about the opening scene, in which an old man pokes holes in shoji screens, he replied, “My grandmother told me that my own grandfather [did that]. When we got to the set and I saw the shoji, I started wondering why he did it. I thought perhaps he was trying to imagine this other world that he was about to enter, and I thought it was a good metaphor for religion: that people are peering into a world that is beyond them or is on the other side.”

He added, “I think it’s important for film to leave a little room for interpretation and not to explain everything. So I intentionally left room in this film. If audiences are able to derive their own meanings from it, that will make it a more personal film for each of them.”

“Notice that the director also leaves room for interpretation with his eloquent answers,” cracked Chad Mullane, suitably claiming the final word.

And with that, audience members moved to the other side, ie., to the club restaurant, which was finally open in the late evenings.

©︎2019 Heikai Sengen

Posted by Karen Severns, Friday, May 10, 2019

Selected Media Exposure

- 奥山大史監督『僕はイエス様が嫌い』チャド・マレーン&佐伯日菜子が登壇!特別試写会レポート

- 「僕はイエス様が嫌い」監督・奥山大史は神を信じるか?見解明かす

- チャド・マレーンが神様役を好演 英語の字幕翻訳も担当

- チャド・マレーンがキリスト役も…「僕はバーターです」

- チャド・マレーン 外国特派員協会の会見で大暴走

TV Exposure

日本テレビ 【Oha!4】<スポタメ>映画「僕はイエス様が嫌い」奥山監督考えるきっかけを…

Read more

Published in: May

Tag: Hiroshi Okuyama, Chad Mullane, Hinako Saeki, religion, independent film, San Sebastian Film Festival,

awardwinning

Comments