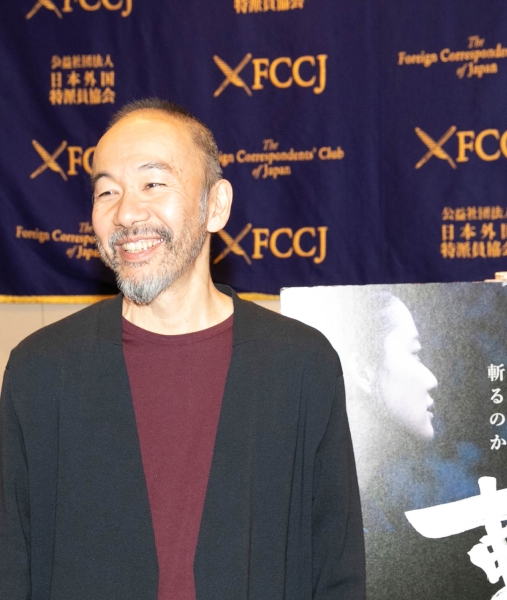

The Film Committee could not have imagined a better inaugural guest for FCCJ’s spacious new digs in Marunouchi: acclaimed writer-director-producer-cinematographer-editor-actor Shinya Tsukamoto.

Nearly three decades on from his 1989 cyberpunk masterpiece Tetsuo: The Iron Man, which hurtled him into international prominence, Tsukamoto has won dozens of awards but remains fiercely independent, creating high art on shoestring budgets, each film the impeccably crafted work of a singular visionary, from Tokyo Fist (1995), Bullet Ballet (1998) and A Snake of June (2002) to Kotoko (2011) and Fires on the Plain (2014, marking his last visit to FCCJ).

Mokunoshin, Ichisuke and Yu watch a sudden duel. ©SHINYA TSUKAMOTO/KAIJYU THEATER

An outspoken critic of the Abe Administration, the director continues his exploration of the moral implications of war in his new masterwork, Killing. Although it is his first jidaigeki period film, the parallels between his depiction of Japan’s bloody past and modern-day militarism cannot be ignored.

Killing is set in the mid-19th century, after 250 years of peace, a time when masterless samurai roam the countryside in search of work and sustenance. Young ronin Mokunoshin Tsuzuki (Sosuke Ikematsu, extraordinary in the role) is helping villagers prepare for the harvest, and has found a friend and sparring partner in Ichisuke (Ryusei Maeda), a farmer’s son. But word has spread about Commodore Perry’s demands and the black ships along the coast. As civil unrest builds in Edo, Mokunoshin knows that he must go there to “prove my worth.” Ichisuke’s sister Yu (Yu Aoi) silently watches the two men training, pining for Mokunoshin. “Will you die?” she later asks him. “No,” he answers, “I won’t.”

Sawamura recruits the young ronin. ©SHINYA TSUKAMOTO/KAIJYU THEATER

When a more seasoned ronin, Jirozaemon Sawamura (Tsukamoto), observes the young man’s sword skills and tries to recruit him for an elite squad that will help “keep the peace” in the capital, Mokunoshin sees it as his duty to join him. But first, he must protect the farmers from a gang of brigands led by ruthless outlaw Sezaemon Genda (Tatsuya Nakamura). Despite promising “We only make trouble for people who deserve it,” they target the hot-headed Ichisuke. What starts as a bout of bullying soon escalates into an ongoing eruption of violence… and through it all, Mokunoshin cannot — or will not — raise his sword to kill.

Whether he is a “pacifist samurai,” as critics dubbed him following the world premiere of Killing in Competition at the Venice International Film Festival in August, remains ambiguous. Short, sharp and shocking though it is, the film is a complex creation, with layers that demand deeper contemplation.

Yu pines for Mokunoshin. His own intentions are never quite clear.

©SHINYA TSUKAMOTO/KAIJYU THEATER

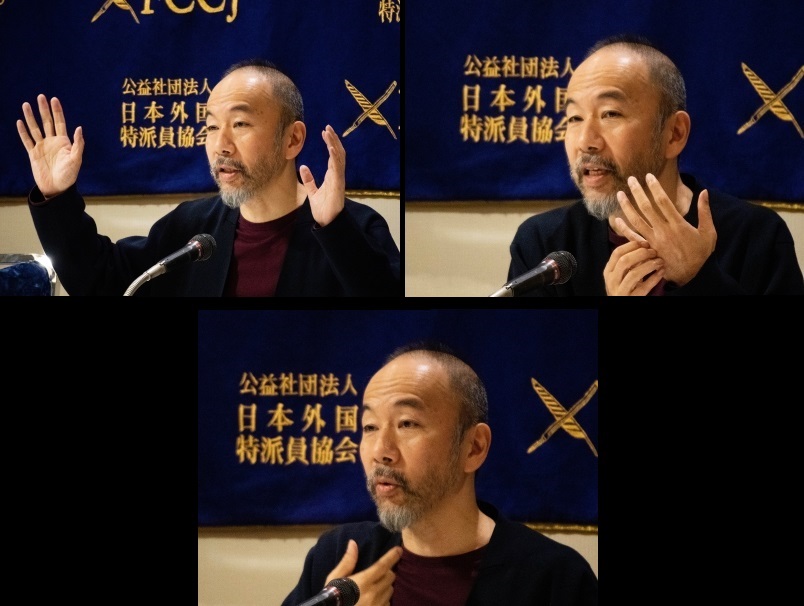

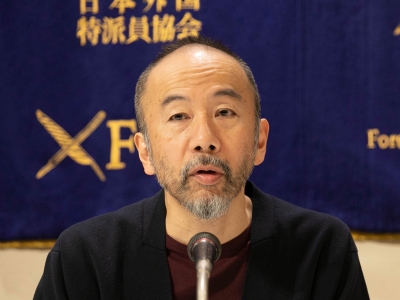

As the director fielded wide-ranging questions following the FCCJ screening, the audience’s obvious enthusiasm for the film fueled Tsukamoto’s own passion for introspection — and gradually, the Q&A session grew nearly as long as Killing itself.

The emcee plunged right in, asking about the film’s seeming correlation between violence and sex. (Tsukamoto later tweeted that he “sat up straighter” when he heard it.) “Indeed, this is a very important factor in the film,” the director acknowledged. “Strangely enough, nobody has asked this question, so I’m very happy you did. Originally, we had a different version of the shooting script ready just before the shoot. That version focused on the samurai studying his sword, pondering the question of whether or not to kill. I thought something was lacking, so I reverted to an earlier version of the script that contained eroticism. Although one could question whether it’s appropriate to equate his dilemma of whether to kill with his sexual urge, I thought the story wouldn’t feel truthfully told without it.”

The director discusses how painful even a small sword slash, like the one Sawamura sustains on his hand, can be. ©Koichi Mori

Noting that the three key battles in the film take place offscreen, an audience member asked whether that was a conscious choice or due to budgetary restrictions. “Although we were on a shoestring budget, it wasn’t because of that, it was a very intentional choice,” the director responded. “I wanted to touch on two themes: I wanted the film to be the antithesis of the heroism that we’re used to seeing in samurai films, and I also wanted Yu to represent all the peasants, the people like us. During World War II, the government told us we were winning, and we were all overjoyed, shouting ‘Banzai!’ We didn’t know what was really happening, all the gruesome details of the reality on the battlefields, where the faces and psyches of Japanese soldiers were being shredded. We [were victims of propaganda and] had no way of knowing

“I wanted to depict the lack of knowledge about what’s happening on the frontlines. It’s only when violence is on our doorstep that we become aware of it. When Yu says, ‘I want you to avenge [her brother’s] death,’ she can say it because she doesn’t know what really happens when someone is sliced open by the blade of a sword. We see the violence drawing closer throughout the film, and I think this echoes what’s happening in everyday Japan. The people who fought in or witnessed World War II are dying away, and we’re gradually losing our sense of danger. I think that’s why we seem to be inching our way toward war. That’s the kind of intent that went into the omission of the battle scenes.”

Super-interpreter Mihoko Imai reacts to Tsukamoto's compliment about her abilities: "Wow, you're so lively!" ©Koichi Mori

He later admitted, “I’m an ardent fan of jidaigeki films and have great respect for [the genre], especially Akira Kurosawa’s Seven Samurai, Yojimbo and Sanjuro. But I wanted to do something a little different this time around, and not focus on what we usually see, which is a kind of beauty of form… I didn’t want to glamorize the battle scenes, as you see done in other samurai films. I didn’t want to go too far, though. I didn’t want to make a jidaigeki film with no battle scenes, just as you wouldn’t want a Godzilla film in which Godzilla doesn’t appear.

“I was aware that, if you’re doing a jidaigeki, the audience expects sword fighting. So where I wanted to make the difference was how the story unfolds leading up to the battle scene. I had to find the balance between the archetypical samurai film and the atypical. The atypical portions should make you a bit uncomfortable and leave you with questions about [what it means].”

©FCCJ

Complimented on the film’s impressive performances, Tsukamoto was asked about his own, as the skilled swordsman Sawamura. How did he summon the heroic-but-murderous spirit needed? He responded, “My impression of the character when I was writing the script was quite different from my impression when I watched the film, which surprised me. We’re used to seeing samurai characters depicted as chivalrous and kind, and I wanted to pose a question about what they were really like. So you should see the antithesis of that in the film. But although I wrote him that way, when I saw him on film, he seemed very villainous, as if he were the cause of all the problems that occur.”

Another audience member complimented Tsukamoto on the “magnificent” sword-fighting scenes and the skill with which the actors wielded their swords, and asked how they’d prepared. “We had a tateshi, a sword-fighting action director, Mr. Tsujii, with whom I’d worked in the past, who gave us direction and advice,” the director responded. I wanted to ground the fighting sequences in reality, so I also sought the advice of a sensei at the Hokushin Ittoryu dojo about how to carry your body and how to sheathe and unsheathe the sword, as well as the principles behind the actions.

Tsukamoto as Mifune as Sawamura. ©SHINYA TSUKAMOTO/KAIJYU THEATER

“Unfortunately, I sprained my lower back while we were shooting one of the sword fights, so for all the high aspirations I had for the battle scenes, I wasn’t able to do much myself… I’d hoped to be like Toshiro Mifune in Yojimbo, where he was slicing and dicing these 10 opponents. I noticed he always carried his back [at the same height] from the ground, which really impressed me. I was really disappointed that I couldn’t do that.”

He joked that he was a better editor than an actor, since he’d had to improve his own fight scenes in the editing room. “I think the reason the sword-fighting sequences look like they’re exquisitely done is because Mr. Ikematsu is so good. He didn’t have much [fighting] experience before, but he’s like a sponge, a very quick learner, and he has great physicality. He elevated the level of [those sequences].”

©FCCJ

He elaborated, “What I wanted to do with Mr. Ikematsu was to transport a modern-day youth back to the Edo period, and bring a sense of reality and rawness to the story. This reflects my influences, including an early formative experience for me, watching Kon Ichikawa’s Matatabi [aka The Wanderers]. That film also had young actors in a period piece that feels very modern.”

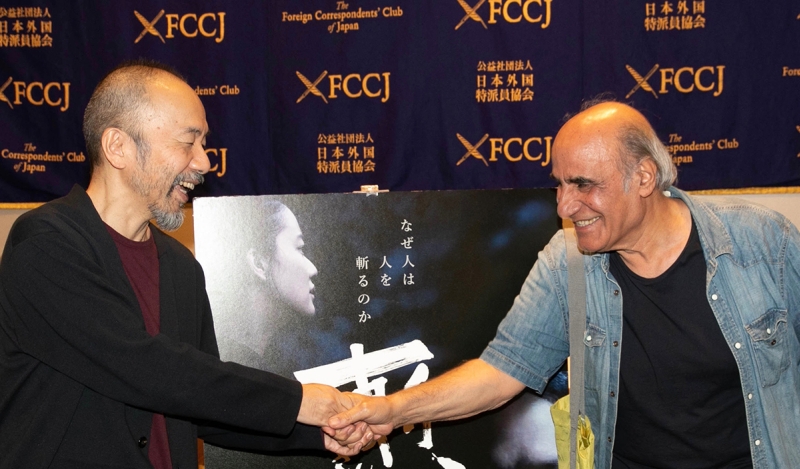

Renowned Iranian filmmaker Amir Naderi was in the audience, and asked how Tsukamoto always manages to direct such “fresh” performances from his female characters, in a way “unlike any other Japanese director.” He answered, “The way I work with actresses depends on the film, of course, but I think you can get the sense in my films that I really respect women, who are amazing … As you know, Ms. Aoi is an accomplished and versatile actress, so I didn’t really have to direct her much. Usually, she can detect the through-line quite easily, but she seemed to find it difficult with my script. So she decided to go at the role from diverse directions, almost as if we see her maturing from 15 to 28 years old, coming of age. It’s wonderful how she did that, and I think she’s marvelous.”

Naderi greets Tsukamoto after the screening. ©Mance Thompson

Naderi had also asked about Tsukamoto’s unique use of sound, “which is almost like music in the film.” The director responded, “I’ve collaborated with the sound designer since A Snake in June, and I think the sound is as important as the visuals. I wanted to make something that you couldn’t just watch objectively; I wanted to make an experiential film. I wanted audiences to feel the presence of nature, since it surrounds the characters, as well as the presence of the blades. They’re very heavy, which you can feel through the sound design.”

He continued, “I used Chu Ichikawa’s music in the film. We’d been collaborators for 30 years, starting with Tetsuo. We shot the film, and just as we started editing, he succumbed to a long-term illness and died. I didn’t have a desire to go to anyone else; I wanted to use his music. It was a rushed shoot (just 3 weeks), but the editing process was lengthy. I used parts of compositions he’d done over the past 30 years. With his wife’s permission, I went to his home and looked for unfinished pieces. It was a mourning process for me. I could collaborate with Mr. Ichikawa, event though he’s up in heaven, and I was able to hear music I hadn’t heard before.”

©Mance Thompson

Calling Killing “one of the finest Japanese films of the past decade,” a critic asked whether Tsukamoto intended to make another trilogy, as he had with the Tetsuo films. “I had this idea of the ronin pondering [the moral implications of wielding] his sword 20 years ago,” said the director. “I was also entertaining the idea of having the protagonist duel with Zatoichi in part II. It would be wonderful to see Mr. Ikematsu doing battle with Zatoichi. I’m interested in the late Edo period, the Bakumatsu era. But there’s a jinx with films depicting that era, they’re usually not successful. I’d like to take up the challenge. I thought it would be interesting to have the guitarist Hotei portray (imperial loyalist) Ryoma Sakamoto, because he’s very, very tall and I think he would look good in hakama and boots, carrying a gun.”

Obviously relishing the image, he went on, “Of course I would then have to depict the Shinsengumi (who murdered Sakamoto), who were in reality a bunch of rowdy outlaw teenagers. Just talking about it makes me smile. I don’t want to strike out the possibility of doing that in the future. If saying it here helps to [get the project off the ground], all the better.”

©Mance Thompson

Tsukamoto has had an active parallel career as an actor in a diversity of films by other filmmakers, including key roles in Martin Scorsese’s Silence and the Japanese blockbuster Shin Godzilla, both in 2016. He was asked whether his experience with Scorsese had left a lasting impact. “Of all the filmmakers alive today, Martin Scorsese is the one I respect the most, ever since I first saw Taxi Driver in high school,” he responded. “I play a Christian who dies for his beliefs in Silence, and I would say that my own religion is Scorsese. I think he’s influenced me in the way he leaves a lot of freedom for his actors. Although he’s so accomplished, he has a wonderful respect for his actors. I learned that from him, and I tried to do a little of that on this film.”

©SHINYA TSUKAMOTO/KAIJYU THEATER

Posted by Karen Severns, Friday, November 09, 2018

Selected Media Exposure

- DC MINI, LA CHRONIQUE DE STEPHEN SARRAZIN – CHAPITRE 10 : LE FERMIER SAMURAI

- 世界を席巻『斬、』公開迫る中、外国特派員協会で塚本晋也監督が会見!イランの名匠アミール・ナデリ監督からの質問--そして塚本版“新撰組”の構想も--

- 「斬、」塚本晋也がアミール・ナデリから賛辞贈られる「女性キャラの扱いが新鮮」

- 塚本晋也監督、新作『斬、』に込めた亡き石川忠さんへの思い

- 塚本晋也監督「斬、」に込めた“時代劇ヒロイズム”へのアンチテーゼ

Read more

Published in: November

Tag: Shinya Tsukamoto, Sosuke Ikematsu, Yu Aoi, jidaigeki, antiwar, Fires on the Plain, awardwinning

Comments