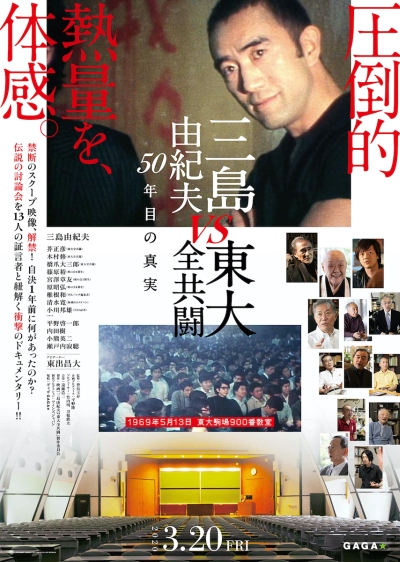

Yukio Mishima: the name still towers over the local literary landscape, especially when viewed from overseas. There is arguably no other Japanese writer whose works have been as widely translated, whose life — and death — have been as well documented internationally, whose controversial reputation has been subjected to such intense scrutiny.

No surprise, then, that many members of the audience who gathered at FCCJ to watch Mishima: The Last Debate had not only read most of his 34 novels (and/or his 50 plays, 25 short story collections and 35 books of essays), watched his film Patriotism, in which Mishima also stars, viewed Paul Schrader’s Mishima: A Life in Four Chapters or Koji Wakamatsu’s 11:25 The Day He Chose His Own Fate. Those with an enduring interest may have also read the essential biographies by John Nathan and Henry Scott Stokes, or Andrew Rankin’s authoritative Mishima, Aesthetic Terrorist: An Intellectual Portrait.

©FCCJ

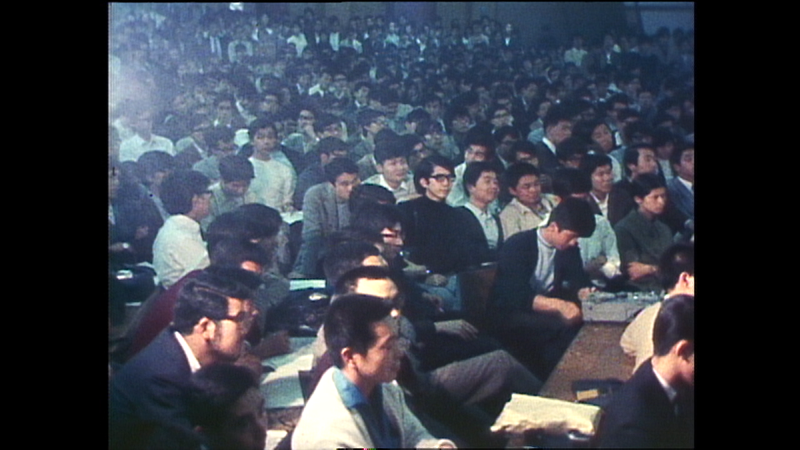

No surprise, either, that several audience members had even been present at the University of Tokyo, where The Last Debate is set, or had firsthand experience of the film’s 1969 time period, 50 years ago, when student rioting was convulsing college campuses across the country.

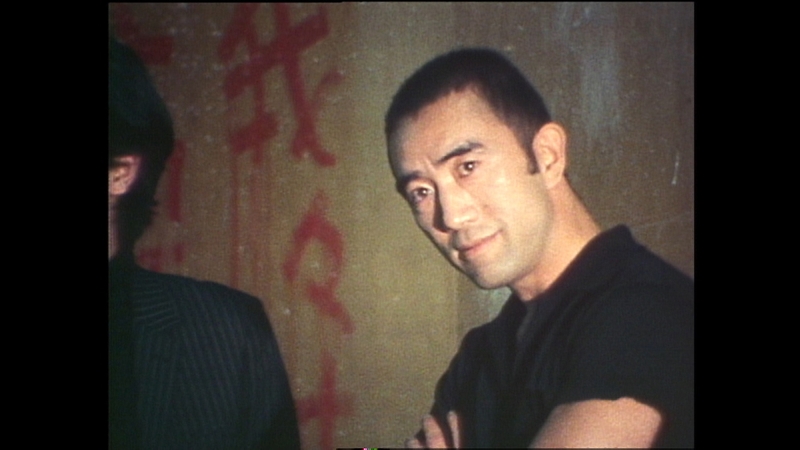

The surprise comes with the revelation of discovering/rediscovering Yukio Mishima, the man. No amount of reading him/about him prepares the viewer for the charismatic rockstar figure who dominates 45 minutes of The Last Debate’s runtime, in long-lost footage of a historic verbal duel between right and left that has been restored to 4K, and forms the centerpiece of the riveting new documentary.

©2020 “Mishima The Last Debate” Film

Surprising, too, is the choice of director. As Keisuke Toyoshima (There Is No Lid on the Sea, Moriyamachu Driving School, Maniac Hero) admitted to the audience, “I’ve been making genre movies, so I was [quite amazed] when I got this offer. TBS discovered at the beginning of 2019 that they had this footage from the 1969 debate, and a TBS producer who was a classmate of mine at Todai was involved in planning a documentary about [the time period]. He wanted to hire a director who [hadn’t lived through it] and thought of me.

“The best-known image of Mishima comes from his controversial 1970 suicide,” he continued, “so a lot of people have this idea that he was an eccentric man with extreme thoughts. That’s the image I had before I started making the film. But the more I learned about him, the more my image changed. It took a 180-degree turn.”

©Koichi Mori

Award-winning novelist Keiichiro Hirano (“The Eclipse,” “Dawn,” “A Man”), who is often compared with Mishima for his acclaim at an early age and the intensity of his intellect, provides expert commentary in the documentary, and joined Toyoshima at FCCJ. “I wasn’t surprised at all by the footage,” he told the audience. “I read my first Mishima novel at 14 and became a big fan of his work. I’ve read all his books, I’ve listened to him on CDs and I read the book about this debate (“Toron: Mishima Yukio vs. Todai Zenkyoto,” Shinchosha, 1969), which I’ve cited in my own writing.

“I’ve also had opportunities to talk with many people who knew Mishima in person, like Tadanori Yokoo, Jakucho Setouchi and Akihiro Miwa. They all talked about how charming he was. Everything they told me was about the genuine, human side of Mishima. So the image I had of him was very similar to how he appears in the footage.”

Although accounts differ about whether all the students were members of Zenkyoto, one can't help wondering how they breathed. ©2020 “Mishima The Last Debate” Film

How he appears is this: Vibrantly cerebral, nearly pulsating with intellectual energy and wit, effortlessly commanding attention from the 1,000 students who were at the University of Tokyo’s Komaba campus on May 13, 1969 to see him. He had been invited by the Zenkyoto (All Campus Joint Struggle Committee) to debate his rightwing views with its revolution-minded members, and Lecture Hall 900 had been declared neutral territory to accommodate the exchange.

At the time, Mishima had already founded the private Tatenokai (Shield Society) militia and trained them (using live ammunition, the film reveals) with the Japan Self-Defense Forces. (Unbeknownst to his soldiers, he had probably already begun planning a coup attempt at the SDF headquarters to restore power to the ‘Emperor,’ which would precede his suicide the following year.)

©Koichi Mori

Providing essential context before focusing on the Todai meeting, Mishima: The Last Debate opens with heartbreaking scenes of Tokyo under siege, as students, radicalized from protesting the Vietnam War and the US-Japan Security Treaty, occupied college buildings and demanded affordable tuition and greater autonomy. Rioting quickly engulfed campuses, culminating in the barricading and burning of Todai’s Yasuda Auditorium, which marked the beginning of the end for Zenkyoto, which had instigated much of the violence.

Their final united act was to invite the “anachronistic gorilla” — as posters at the door crudely depicted him — to defend his views. “I came to see if words are still an effective method of communication,” Mishima tells the students in his 10-minute opening speech, and proceeds to amuse, impress and engage his audience with the mental agility of a gold-medal gymnast. Beating back each counterargument with poetic logic, he never once condescends, antagonizes nor treats his audience with disrespect.

But then he seems to meet his match in a smiling young man with a Buster Brown haircut and a baby in his arms. For a good 15 minutes, the documentary circles around Mishima’s increasingly theoretical interchange with Masahiko Akuta (who would go on to become an experimental theater pioneer, working with the likes of Shuji Terayama), until a student yells, “This is all philosophical nonsense! I’m here to see Mishima get beaten up!” And while this never happens, for many audience members, the earth moved that day.

©Koichi Mori

This much is clear from many of the commentators whom Toyoshima interviews in the film — including Akuta himself (still blazingly brazen), former University of Tokyo students, former Shield Society members and of course, Keiichiro Hirano — allowing them to elucidate and expand upon the debate in ways that are extremely valuable.

“Before I started making the film,” recalled Toyoshima, I did a lot of research and read a lot of books about Mishima. Most of them start by asking why he died, why he had to die, what was the story behind his death. I didn’t want to add yet another interpretation to all those that have been done. Instead of looking at the debate from the point of view of why he died, I wanted to focus on his life.

A match made in philosophical heaven: Masahiko Akuta and Mishima

©2020 “Mishima The Last Debate” Film

“The reason I included the footage [from just before his] suicide at the end of the film is because I felt there was an interesting juxtaposition to be made between the 1,000 students in the hall during the debate, when his words really seemed to be reaching them, and the 1,000 members of the Self Defense Forces, who did not accept his message. I thought that comparison could be very interesting.

“The other reason is that I came to realize I was making a film about those who happened to meet Mishima during their lifetime, not about Mishima himself. The more people I talked to who were there during the debate, the more obvious it became that their encounter with him had had a powerful impact on their lives. In some cases, it even seemed to determine the future course of their lives.

©2020 “Mishima The Last Debate” Film

“So I included the suicide because I wanted to focus on how those people who spent the day at Todai on May 13, 1969 felt about his death, about his loss. It’s not about the meaning of his death, but about how his loss was received by those who were there.”

Inevitably, the FCCJ audience wanted to know how the filmmaker and the novelist felt about Mishima’s stated hope to reify Japan under the concept of the emperor.

Hirano dove right in. “Mishima’s attitude right after the war was very critical of society and the LDP. That’s quite different from today’s conservatives, who only want to praise Japan. He spoke about an ideal image of Japan that derived from his prewar education, which was centered on [emperor worship] when he was young.

©Koichi Mori

“But he also tried to adjust to what was happening in Japanese society, to separate himself from his early idea of the emperor. He was successful in that, in the sense that he became a superstar novelist and a frequent presence in the media. He wasn’t really aligning himself with a democratic society, but he did embrace the materialistic aspects of [Japan’s capitalistic culture]. But he was tired of this by his mid-30s and reverted to his earlier image of the ideal Japan, and its [abstract traditional essence] under the 'Emperor.'”

Added Toyoshima, “As you saw in the film, Mishima says to the students, ‘If you’d said ‘Emperor,’ I’d have joined you’ [in their cause]. I wanted to understand why he said such a thing, and that was one of the motivations for me to interview so many people. I would be curious to know what Mishima would think of our current definition of tenno, since the Heisei Emperor (who abdicated the throne in 2019) seemed to support the constitution and traveled around the country trying to help people heal (after tragedies like 3/11). The recent emperors seem to sympathize with leftwing ideals.”

©Koichi Mori

Toyoshima stresses that although Mishima wielded both pen and sword, it is the former that has had the greatest lasting impact. Rarely has a film captured the dynamic interchange of ideas and the power of language in quite so compelling a form. Mishima: The Last Debate is a timely reminder that words, wielded judiciously and meaningfully, will always triumph over swords; that there is always a common ground even when arguing political ideologies at opposite extremes.

Is it possible, Hirano was asked, for political discussion in today’s world to remain civilized and courteous? “I can’t generalize about the current situation,” he responded. “I’m around the same age as Mishima when he was debating the Todai students, so as much as they seemed to be on an equal footing, I still think there was the sense that [an adult was talking to students], and students were talking with a star novelist.

©FCCJ

“But there was a kind of balance which made the debate very gentlemanlike, even when the students tried to provoke him. There was a power balance. Today, especially on the internet, it’s nearly impossible to have a constructive conversation like this between people of opposing opinions. But I think in the proper venue, it is still possible.”

Toyoshima concurred. “I hope this film and the footage of the debate will communicate the passion and respect that were present that day. You see how the opinions were exchanged, how close physically the debaters actually were as they talked. Making the film, I wanted to believe in Mishima’s opening remarks — that words are still an effective means of communication.”

And so, it goes without saying, do we.

©2020 “Mishima The Last Debate” Film

Posted by Karen Severns, Thursday, March 19, 2020

Selected Media Exposure

- Review: Mishima, the Last Debate

- 三島由紀夫の理想の日本とは ドキュメンタリー「三島由紀夫VS東大全共闘」平野啓一郎氏、豊島圭介監督が会見

- 三島由紀夫ドキュメンタリーで会見 平野啓一郎氏「今の保守層が『日本はスゴい』と言うのとは違う」

- 三島由紀夫は「イメージとかけ離れていた」と豊島圭介監督

Read more

Published in: March

Tag: Yukio Mishima, Todai Zenkyoto, Keisuke Toyoshima, Keiichiro Hirano, Akutagawa Prize, documentary

Comments