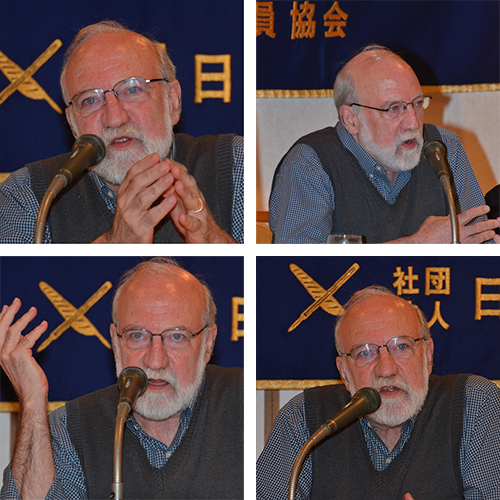

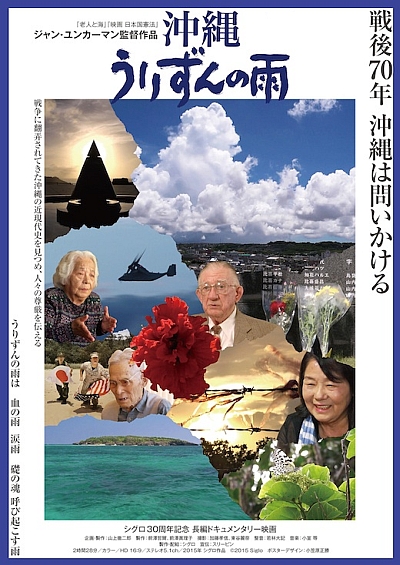

At 6:00 pm, an hour earlier than the usual start of FCCJ screening events, writer-director John Junkerman reassured a surprisingly large audience, “I’ve been told that the film doesn’t feel as long as it actually is.” At 9:30 pm, as the hour-long Q&A session was winding down and hands were still going up, the true extent of his accomplishment became clear. Not only was there consensus that the film’s 148-minute length was warranted by the complexity of its subject, but with the exception of one vocal dissenter, praise was effusive for Junkerman’s even-handed illumination of the troubling history of occupation, human and civil rights violations, and dogged resistance in Okinawa — an ongoing flashpoint in US-Japan relations that is drawing even greater attention in this, the 70th anniversary year since the end of World War II.

The club’s screening of Okinawa: The Afterburn was held just days after Okinawa Gov. Takeshi Onaga’s return from a trip to Washington, DC, where the US departments of State and Defense confirmed their “unwavering commitment” to go forward with construction of the huge new Marine base in Henoko, despite convulsive and constant protests from Okinawans for over a decade, and just weeks ago, a crowd of some 35,000 protestors surrounding the Diet in Tokyo.

Junkerman's history with Okinawa goes back to the mid-1970s.

Junkerman, Academy Award®-nominated director of Hellfire: A Journey from Hiroshima, among a slew of award-winning documentaries like Power and Terror: Noam Chomsky in Our Times and Japan’s Peace Constitution, opens his landmark new film with Adm. Matthew Perry, who arrives in the Ryukyu Kingdom in the 1850s and immediately sets about trying to claim it. Some 90 years later, his plans finally come to fruition: After the 84-day-long Battle of Okinawa, the bloodiest conflict of the Pacific War, has taken the lives of some 240,000 people, the US begins its occupation of Japan’s southernmost prefecture. The film makes it clear that, despite its reversion to Japan in 1972, the island is still occupied.

With the active support of the Japanese government, America has continued to treat Okinawa as the spoils of war — its “keystone in the Pacific.” Today, the US military occupies nearly 20 percent of the island, accounting for 75 percent of its military presence in Japan. As Junkerman noted during the Q&A, “That’s just 0.6 percent of the entire territory Japan, and that’s an unfair burden, a tremendously large burden. The only way, I think, of explaining that is to understand that Okinawans are [considered] second-class citizens. They don’t have the same status as mainland Japan.”

Producer-collaborator Yamagami has a 30-year friendship with Junkerman

and has produced 5 films about Okinawa.

Junkerman lived on Okinawa in the mid-1970s, and was struck by “the pervasive and abiding rejection of war among the Okinawa people, and by how incongruous and violent the American military presence on the island was. Over the decades that followed, it troubled me that Okinawa was forced to continue to endure this incompatibility. This is largely a consequence of the ignorance of the American public, and I felt a responsibility to make a film that would penetrate, if only in a small way, this shroud of apathy.”

Junkerman and his close collaborator, Tetsujiro Yamagami, the founding president of social-issues film company Siglo and the producer of five previous films about Okinawa, attempt to pierce the shroud through interviews with American, Japanese and Okinawan survivors of the Battle of Okinawa, tracing its fraught legacy. The director makes crucial use of footage shot by the US during the course of the war; but his trademark approach is to allow eyewitnesses to relate history as they lived it, and Okinawa: The Afterburn features several revelatory accounts. Issues of wartime guilt are movingly recalled by such survivors as Hajime Kondo, who admits that the Japanese sense of superiority over the Ryukyuan people accounted for some of the war’s worst atrocities: “We committed many abuses here in Okinawa,” he laments. Others recall the Chibichiri-gama mass suicide-murders, the 140 comfort stations staffed with “pigua” (comfort women), and the students who were forced by Japanese troops to throw bombs underneath US tanks.

Although there have been frequent problems with the US presence over the years, from dangerous helicopter crashes to water supplies poisoned by jet fuel, opposition to US bases expanded most dramatically after the 1995 rape of a 12-year old girl by three American servicemen. One of them is interviewed to devastating effect in the film, and his chilling testimony is just one of the many reasons that Okinawa: The Afterburn is a must-see work. “To interview the perpetrator was something that we debated long and hard,” said Junkerman, “but we felt the need to convey to our audience the true nature of that rape, and to do so, we needed to hear both sides.”

Junkerman is aware that there is a sense of fatigue in Japan, where Okinawa is the subject of fairly constant TV documentaries, and said that he and Yamagami knew they must “do something that those films don’t do — break through the barrier of people who think they’ve seen enough of Okinawa and know the subject. There is a lot that isn’t expressed. We didn’t concentrate on recent developments… we felt that the historical context was neglected, and once one has a better grasp of the historical roots, then one understands why the problems exist. And we also understand why they’re so tenacious and difficult to solve.”

Junkerman hopes to screen the film across America.

Yamagami was queried about his selection of an American director to revisit an essentially Japanese history. “I don’t really think of John as being a foreigner,” he admitted. “We’ve known each other for over 30 years and worked together on several films. For me, the key to a successful collaboration is to have a relationship of trust.”

In a “response to the film” printed in the press notes, historian John Dower notes: “No place in the world surpasses Okinawa as a symbol of the bitter legacies of war since World War II. And no voices are more eloquent in calling for peace and equality than the voices of the people of Okinawa…despite the oppression and discrimination we encounter [in the film], the voices we hear are so dignified and articulate that one emerges not just with understanding and admiration, but also with hope.”

Indeed, Junkerman reminded the FCCJ audience that the report commissioned by Okinawa Gov. Onaga to review “the process of decision-making that went into moving ahead with the Henoko base,” is due next month, and “there are a lot of political questions concerning the previous governor’s approval, after he had been voted out of office, but before his successor took over, of four permits that were crucial to building the base at Henoko. That seems to me to be a violation of democratic process and democratic rights. As a lot more people are becoming aware of that, it’s becoming less possible for people in Japan to look the other way.”

— Photos by Koichi Mori and FCCJ.

©2015 SIGLO

Posted by Karen Severns, Friday, June 12, 2015

Media Coverage

- ‘Okinawa: The Afterburn’ sheds light on the ferocious anger against U.S. bases

- Okinawa: The Afterburn (Urizun no Ame)

Read more

Published in: June

Tag: John Junkerman, Tetsujiro Yamagami, documentary, awardwinning, Okinawa, Henoko, World War II, US Occupation

Comments