Imagine that you are an animator of short films — a very, very good animator, an award-winning animator, but nevertheless, a short-form animator — and out of the blue one day, you receive an email from Studio Ghibli.

The email asks you two questions: Would you allow us to distribute your Oscar-winning Father and Daughter in Japan? And would you be interested in working with Studio Ghibli on your first-ever feature film?

London-based Dutch animator Michael Dudok de Wit laughs when he recalls that magical moment in November 2006, when his life changed: “It was a shock when it all started …[the email explained]: ‘You would team up with Wild Bunch in Paris, and you would write the film.’ I had two simultaneous reactions: The first one was ‘Yes!!’ And the second one was, ‘Hang on.’ I wrote back and asked, ‘Could you please explain? I want to make sure that I understood your email properly.”

© 2016 Studio Ghibli - Wild Bunch - Why Not Productions - Arte France Cinéma - CN4 Productions - Belvision - Nippon Television Network - Dentsu - Hakuhodo DYMP - Walt Disney Japan - Mitsubishi – Toho

The director then met right away with the heads of Wild Bunch in London, and, “My first question was, ‘This is unbelievable. Tell me, is there’s something I’ve not been told yet?’ They said, ‘No, no, this is really genuine. They want to know if you have a story. We aren’t promising that we will make the film, but we’ll have a go. It’s new for [Ghibli], it’s new for you to make a feature film, so let’s take it step by step.’ Straight away, I started writing the synopsis.”

As far as fantastical genesis stories go, it’s a suitably Ghibli-esque one.

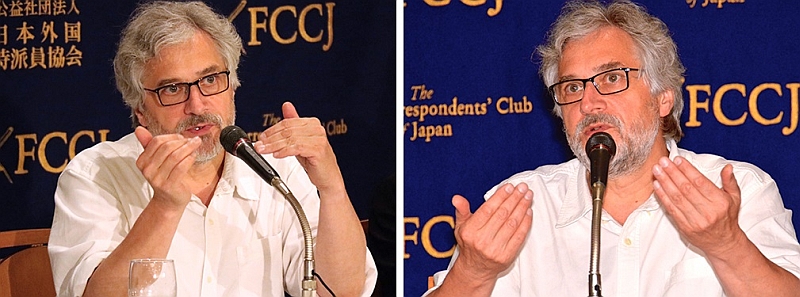

Dudok de Wit shared that anecdote and many others with FCCJ’s audience during a lengthy Q&A session following a sneak preview screening of his first feature, The Red Turtle — which also became Studio Ghibli’s first international coproduction, in collaboration with France’s Wild Bunch and Why Not Productions. Watching proudly from the audience, and later responding to a question, was legendary Studio Ghibli producer Toshio Suzuki.

Suzuki responds, essentially putting the kibosh on the

Ghibli-collaboration fantasies of animators everywhere. ©Koichi Mori

Since it was the question on everyone’s mind at FCCJ, and is surely foremost on the minds of those reading this blog, we’ll cut to the chase:

Suzuki was asked whether The Red Turtle was to be the first of many international projects to come from Studio Ghibli. He responded: “I think Michael is a very special case. In my line of work, I meet many different people and I often becomes friends with them. But as one of the producers of the film, what got me started on this was falling in love with Michael’s short film, Father and Daughter, and simply being curious: What would a feature film by this director look like? That was the impetus for the film, and if you’re asking if this project will be a catalyst for future collaborations with foreign filmmakers, I would have to say, it simply depends on whether I encounter a similar situation like that again.”

In the ensuing decade since Dudok de Wit received his life-altering email, many things changed, not least the makeup of Studio Ghibli itself, after anime titan Hayao Miyazaki retired from long-form filmmaking in 2014, and Suzuki stepped down from producing in 2015. But in May 2016, The Red Turtle premiered at the 2016 Cannes Film Festival, winning the Un Certain Regard Special Prize and a slew of rapturous reviews. As Indiewire raved: “It showcases the best ways in which Studio Ghibli productions maintain a certain elegant simplicity that points to deeper truths. This is a quiet little masterpiece of images, each one rich with meaning, that collectively speak to a universal process.”

Photo left ©Koichi Mori; right, FCCJ

Throughout the Q&A session, Dudok de Wit stressed just how universal the process of creation had been: “For a feature film, you want to make sure your [choices as director] work for other people as well. So I was very sensitive to how [Studio Ghibli and Wild Bunch] reacted during the development process. After that, we became a team: the animators arrived and the background artists arrived, and we were dozens of people in the same building, making the film.” Over the three years of production, the director constantly encouraged feedback from his team, as well as reading nonverbal signals and body language — something he emphasized every animator does.

One journalist remarked immediately on the film’s similarities with Ghibli releases. Responded Dudok de Wit: “I don’t think there’s a typical Ghibli aesthetic. I think there’s a [Hayao] Miyazaki aesthetic and a [Isao] Takahata aesthetic. There’s a sensitivity and a maturity about the films that is very obvious, but it was never the idea to make a film that looks like a Ghibli film. From the beginning, [Takahata, who is credited as the film’s artistic producer, and Suzuki] said, ‘We like Father and Daughter a lot, we feel like it’s a Japanese film,’ which is a huge compliment. I would not have been good at imitating their style. I find it extraordinary to make a haiku-style film like Takahata’s My Neighbors the Yamadas. We could never do that in the West.”

©Koichi Mori

He continued, “What we do have in common is a certain sensitivity. We have a respect for nature and a deep, positive respect for human nature. To be honest, I felt it clicked between us. There was a sort of natural chemistry between us.”

That chemistry translates onscreen into a perfect synthesis of animation sensibilities. The Red Turtle is an expressionistic ode to human resilience, to family bonds, to the search for happiness and to the very cycle of life. Stripping existence to its most basic elements, the breathtakingly visual film follows a man who washes ashore on a deserted island following a ferocious storm, eventually builds a raft to escape and is prevented from leaving by an enormous red turtle. One morning, he awakens to find that a woman has become a castaway with him on the island, and after a courtship of sorts, the two have a child.

As their odyssey continues, Dudok de Wit’s hand-drawn charcoal backgrounds and the artisanal quality of his digital animation imbues his allegorical tale with a delicate, painterly beauty. While uniquely the director’s, The Red Turtle warmly evokes Ghibli, especially in its Greek chorus of sand crabs who are the man’s only friends at first, and the unmistakable message that man can only survive if we learn to coexist with nature.

(Variety called the film “a fable so simple, so pure, it feels as if it has existed for hundreds of years.” In fact, although the titular turtle was Dudok de Wit’s idea, the story has faint echoes of the Japanese myth of Urashima Taro, which also features a turtle and a lost soul).

When one journalist lauded the director for “creating a world within the film, a world that we come away remembering vividly, as we do with Ghibli films,” Dudok de Wit reassured him that animators “usually do far more research than spectators realize, taking thousands and thousands of photographs, because that’s our job. And it’s a joy. I went to La Digue, one of the Seychelles islands, particularly because it has ancient granite rocks. I thought they were very beautiful, very sensual.” He also mentioned that he’d purposely chosen something different from one palm tree with a coconut, as deserted islands always are in the castaway clichés. He found his inspiration in a famed bamboo grove near Kyoto and a wild bamboo forest in Kyushu, as well as another in France.

©FCCJ

To a question concerning his choice to make the film dialogue free, Dudok de Wit said, “There were a few moments, later in the story, where I felt it was essential to have a few sentences, both for the clarity of the story, and to enhance the humanity of the characters … But new arrivals on the film team would say, ‘I like the story a lot, but the voices are a bit odd.’ [With writer Pascale Ferran,] we kept working on the lines, and in the end, we kept just a few … Then one day I got a call from Studio Ghibli, saying, ‘We looked at the animatic [storyboard] and looked at the words the characters are saying. We discussed it, and we feel that the film actually doesn’t need dialogue.’ I defended my idea that we occasionally needed it for clarity, but in the end, they said ‘We think the film will survive without dialogue and will actually be stronger.’ At that point, I felt a huge relief. I thought, ‘If they feel it works without dialogue, I’m really interested in this challenge.’”

He then discovered a way to bring the characters more alive without having them speak: “We got voice actors in, and we asked them to breathe through the whole film. To my pleasant surprise, the breathing not only created a stronger empathy for the characters, but the sound of breathing was more expressive than I’d anticipated. We don’t need to hear words, but the fact that we hear them breathe brings them closer to us.”

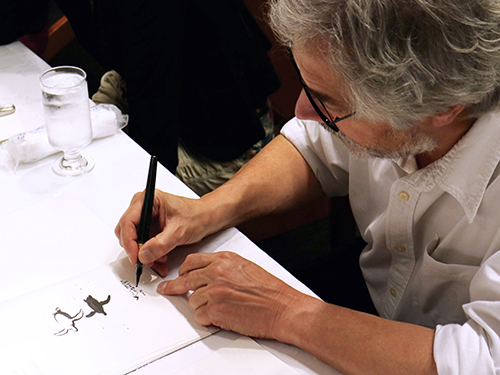

Dudok de Wit embellishes his autograph with a quick sketch of the titular turtle. ©Koichi Mori

All of Dudok de Wit’s short films, including the Oscar-nominated The Monk and the Fish (1994), a playfully absurd comedy, and his achingly poignant Oscar winner Father and Daughter (2000), are driven by music, with no dialogue at all. Asked whether a future film might include lines, the director said, “There are many, many short films with no dialogue. That’s very common. They don’t need the spoken language, the film language is already strong enough. In this film, the [main character] doesn’t need to speak aloud to himself; he’s not like Tom Hanks. I would be open to using dialogue [in future]. I’ve used dialogue in many of the commercials I’ve made.”

The Red Turtle is coming soon to screens around the world, since most territories have been sold. It has opened in France, Belgium and the French-speaking part of Switzerland, and Sony Pictures Classics will be releasing the film later this year in North America. It’s sure to attract animation and art-film lovers everywhere, as well as making all the animation award shortlists at the end of this year. But will it lead to more magical emails from Studio Ghibli, winging their way across cyberspace to transform the lives of other animators…? Only time will tell.

© 2016 Studio Ghibli - Wild Bunch - Why Not Productions -

Arte France Cinéma - CN4 Productions - Belvision -

Nippon Television Network - Dentsu - Hakuhodo DYMP -

Walt Disney Japan - Mitsubishi – Toho

Posted by Karen Severns, Friday, September 02, 2016

Media Coverage

- ‘The Red Turtle’: Studio Ghibli takes an intriguing turn

- The Red Turtle

- スタジオジブリ最新作『レッドタートル ある島の物語』、セリフがない理由は?

- マイケル・デュドク・ドゥ・ヴィット監督/『レッドタートル ある島の物語』日本外国特派員協会

- 「レッドタートル」監督、ジブリ作品への理解示すも「模倣しようとは思わなかった」

- ジブリ、今後は海外監督とのコラボ予定なしか「マイケルは特別」

- 『レッドタートル ある島の物語』ヴィット監督が会見、ジブリが描く「自然への敬愛、人間の有様」に共通点。

Read more

Published in: August

Tag: Studio Ghibli, Michael Dudok de Wit, animation, Oscar, awardwinning, Cannes Film Festival, international coproduction

Comments