The FCCJ has hosted many a press conference devoted to what is perhaps the most incendiary flashpoint in Japan’s postwar relations with Korea and China. Since the early 1990s (at least since 1991, when Hak Sun Kim became the first Korean to testify about it), the comfort woman issue has spiraled into a seemingly insurmountable impediment to improving ties in the region.

The internet has encouraged a proliferation of counterproductive arguments and counterarguments about the treatment of these women, casting doubt on “the truth” and creating an increasingly bifurcated divide. One side supports the victims, who have given moving accounts of the outrages perpetrated against them; the other side insists the women were well-paid prostitutes and the Japanese government was not complicit in “creating a massive, organized rape system,” as has been charged.

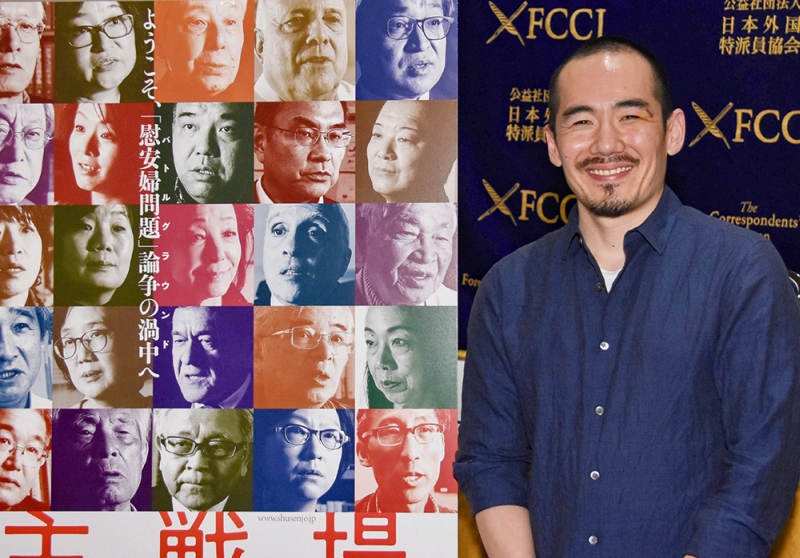

©FCCJ

Surprisingly, until Miki Dezaki’s Shusenjo: The Main Battleground of the Comfort Women Issue, there has not been a feature documentary that thoroughly investigates the facts, figures, opinions and distortions of both sides. For this reason alone — and there are many, many others — the film is absolutely essential viewing.

Appearing at the jam-packed Q&A session following FCCJ’s screening, the director told the audience: “I always get the question ‘Why did you make this film?’ And one of the reasons why is that I thought a 2-hour film could flesh out or give context to this issue that the media aren’t able to do in the short time they have to report on it … I thought maybe there needed to be a more comprehensive introduction to the issue, to remind ourselves how we got here.”

Unless you’re a member of a neo-nationalist group with ties to Japan or a devoted fan of Japan-focused YouTube videos, you’ve probably never heard of Dezaki, aka Medama Sensei. In 2012, the Japanese-American teacher (as well as former Buddhist monk and graduate of Sophia’s Global Studies Graduate Program) raised uyoku (far-right) ire by posting a short video called “Racism in Japan,” in which he discussed zainichi Koreans and burakumin outcasts. It led to relentless online attacks by Japanese neo-nationalists, ongoing harassment, even death threats.

The placement of comfort women statues in California has aggravated

tensions even further. ©No Man Producions LLC.

Realizing that deeper issues were at play, Dezaki eventually decided to meet the challenge head-on.

He spent the next several years conducting the type of balanced, in-depth reporting that was once the purview of the news media. On his own dime, he criss-crossed the globe, meeting with a wide-ranging group of experts and eyewitnesses, amassing footage from milestone events dating back to before WWII, even conducting man-on-the-street-style interviews. Then he edited it all into a comprehensive, comprehensible whole.

Shusenjo does a remarkable job of exploring, explaining and de-sensationalizing this most contentious of disputes in Asia, this “gross human rights violation” that has also impacted the lives of women in China, Taiwan, the Philippines, Indonesia, Burma, Malaysia, East Timor and Micronesia.

Tokyo's Yasukuni Shrine, where war dead are enshrined. ©No Man Producions LLC.

Dezaki casts himself as the lead inquisitor and seeker of understanding in the film, and patiently counters arguments on both sides of the ideological divide. Shusenjo probes a range of crucial questions: Were all comfort women “sexual slaves?” What does “coercive recruiting” really mean? Does the often-inconsistent testimony of the elderly victims even matter? Does Japan have a legal responsibility to apologize? Are the Chinese paying for those comfort women statues in California? Where the hell is the smoking gun? Why are venerable newspapers like the Japan Times “redefining” their vocabulary around the issue? And what does it all have to do with Shinzo Abe’s march to remilitarize Japan?

Shusenjo lays out a complicated timeline of acceptance of facts and increasingly aggressive denials, with unexpected confessions and revelations that allow Dezaki to deconstruct the dominant narratives and uncover the hidden intentions of both supporters and detractors. Few, it turns out, are innocent of fanning the flames of outrage.

©FCCJ

The filmmaker was asked whether his opinion had changed during the process of making the documentary. Dezaki nodded. “I think I was like every other American who’s read about this issue in the newspaper. It’s taken as fact in America that there were 200,000 women, and they were sex slaves who’d been forcibly recruited. I had no information to rebut that, so I took that as fact at first. Through research and interviews — I actually interviewed more people on the conservative side first — I started to question a lot of things that I thought I knew.

“I didn’t have anything to rebut them with, either. I had this constant going back-and-forth as I was making the film. That was emotionally difficult because, as human beings, we want to have an idea of what’s right. We don’t want to waver and be in the middle. I wanted the audience to feel that as they watched the film. There were times I was challenged and re-challenged on a lot of issues. I had debates and discussions with my co-producer and associate producers, and I didn’t come to my conclusions until the editing stage of the film.”

Young supporters of the comfort women in Korea. ©No Man Producions LLC.

Among the many interviewees who appear in the film, familiar names to those who follow the issue, are Yoshiko Sakurai, Mio Sugita, Yoshiaki Yoshimi, Koichi Nakano, Kent Gilbert, Tony Marano, Nobukatsu Fujioka, Mina Watanabe, Setsu Kobayashi, Hirofumi Hayashi. Still, one attendee was critical about the “lack of balance” between the film’s talking heads. “You interviewed a lot of scholars who support the comfort women,” he said, “but you didn’t interview many on the other side. Obviously, you knew Prof. Ikuhiko Hata. Did he decline to be interviewed? Do you know Tsutomu Nishioka, a leading professor? I spoke to him and he said that you never approached him.”

(Hata is a historian and retired professor of international relations who has written about the comfort women. Nishioka is a Korean studies professor at International Christian University who has also written extensively about comfort women.)

Responded Dezaki, “One of the first persons we wanted for the film was Professor Hata. The problem was that he asked us first to interview Prof. [Etsuro] Totsuka and Prof. [Yoshiaki] Yoshimi, so that he could respond to them. So once we did that, we went back to him. He said, ‘Please write a proposal.’ So we wrote a proposal for him. I talked with him on the phone once after that. He said, ‘Call back.’ I called back and his wife answered. She said, ‘Please call back in the evening.’ As an American, I don’t think it’s polite to call people in the evening about work. So I called back the next day, and he was very upset that I didn’t call him in the evening. Because of that, he didn’t want to be interviewed.

©Koichi Mori

“As for Tsutomu Nishioka, I was planning on interviewing him towards the end. But when I was reading the materials he’d written online, I noticed that a lot of things he said were very similar to many of the things that had already by said by many of the people I’d interviewed before. I didn’t feel like I needed that footage again.”

Shusenjo had its world premiere, aptly, at the 2018 Busan International Film Festival. Asked how it was received in South Korea, Dezaki said, “The response was interesting. I do criticize the comfort women supporters to some extent [in the film]. I don’t think they felt totally comfortable with the film. But one of the comments I got, from a young Korean woman, was that she was surprised so many Japanese people supported the comfort women. For her, this was a kind of Japan-Korea battle, but [now] she realized it was more of a human rights issue. I think that shows how biased the media are not only in Japan but also in Korea on this issue.”

©Koichi Mori

Calling the film “powerful and important,” another attendee asked where Dezaki had procured the rare historical footage of Korean comfort women that is used sparingly in the film. Said the director, “I got it from my South Korean associate producer, who got it from Korea’s MBC Broadcasting. I didn’t use too many testimonies in the film [because] there are many films already with extensive footage of the comfort women’s testimonies.”

The Glendale and San Francisco statue-placement disputes are included in the film, and Dezaki was asked what he thought the US position was. He responded, “I don’t think they necessarily care about this issue that much, but they know it’s a big sticking point between the two allies, [so] whatever they can do to bring the allies closer. With the [2015 agreement between Japan and South Korea], I think they felt it was finally something that could be resolved. Prior to that, they had the House Resolution 121 that was demanding that Japan apologize for this. The [2015] agreement was kind of a shock to a lot of people in Korea who support the comfort women. The American government sort of flipped on this issue and I think it’s probably because they don’t care much about it.”

“What do you think it would take for the Japanese government to do to satisfy those Koreans who are most invested in the issue?” asked another audience member. Said Dezaki, “I really don’t want to speak for them, but what I oftentimes hear from them is that they would like this to be taught in schools and they would like a Diet resolution passed, similar to what [then-President] Reagan did. It seems that they don’t care about the [reparations] money so much, from what I understand. I think for them it’s more about passing on that history.”

©FCCJ

Dezaki was asked why he’d relied on his “own research and analysis, rather than interviews,” in the section of Shusenjo that explores the position of the Abe Administration vis-à-vis the comfort women. Admitting that he had used the narration mainly to pick up the flagging pace, the director answered: “This is a film on the comfort women issue, but in the opening, I ask why the revisionists, or the so-called denialists, want to censor or silence the issue. That’s the overarching theme of the film. What led me there was realizing that there was this connection. The question for me was why do they care about this so much? Why was the Japanese government sending an amicus brief for the Glendale statue trial? That’s a pretty big thing for a government to do for a small trial. I went down that path and tried to find the answer.”

Finally, the filmmaker was asked whether the government had asked for a special viewing of the film. “I would love for the Abe Administration to see the film, that would be great” said Dezaki. “I don’t know if they want to. I can’t go into too much detail, since I don’t want to get anyone in trouble, but when I was in Europe showing the film at a private [university] screening, the Japanese consulate in that city contacted the professor and said, ‘Why are you showing this film? Please come to the consulate to talk about this.’ So I guess it’s on their radar to some extent.”

©No Man Producions LLC.

Posted by Karen Severns, Sunday, April 07, 2019

Selected Media Exposure

映画に込めた思いを聞く

『慰安婦問題論争 主張・反論 映画に 日系米人が取材・監督』朝日新聞 朝刊 2019年04月19日

Read more

Published in: April

Tag: comfort women, documentary, Busan International Film Festival, JapanKorea relations

Comments