The phrase “film franchise” invariably evokes mega-budget Hollywood series like Harry Potter, X-Men, even James Bond. So when producer Miyuki Takamatsu told the FCCJ audience that Ten Years Japan represented a new type of arthouse franchise, it gave them pause.

Takamatsu, founder of the sales and distribution firm Free Stone Productions, decided to become a franchise player after seeing the angry, dystopian omnibus film Ten Years, in 2015. Co-directed by five young filmmakers in Hong Kong, it had been inspired by the Umbrella Movement that began shaking the colony in late 2014, and imagined an exceedingly bleak future under China’s tightening control.

Surprisingly, Ten Years went on to win Best Film at the HK Film Awards, causing China to black out the awards show and to ban the film. Nevertheless, it earned HK$6 million in covert, self-distributed screenings, and was seen around the world.

Miyuki Takamatsu, producer and "franchise" founder. @Mance Thompson

Along with that film’s international sales agent, Felix Tsang, and former Fox executive Lorraine Ma, Takamatsu discussed taking the concept regional. They formed a partnership called Ten Years Studio and in 2017, announced a trio of follow-on projects, with films to be made concurrently in Taiwan, Thailand and Japan.

Takamatsu then convinced Palm d’Or-winning auteur Hirokazu Kore-eda to sign on as executive producer of the Japanese version, which like its counterparts, is thematically and stylistically varied, as well as deeply thought-provoking. Ten Years Japan may lack the urgency and political spitfire of the original, but its quiet, contemplative approach does not mask its overall vision of hopelessness.

Speaking fluently in English and Japanese, Takamatsu told the FCCJ audience: “I think this is the first experience for the film industry around the world that a concept has been shared. Pick five directors, each of them makes a short film of less than 20 minutes, and freely expresses how their countries will be in 10 years. I think it was quite interesting to expand the concept to other countries, and after these first three, we are hoping to have Ten Years Korea, Ten Years India and more.”

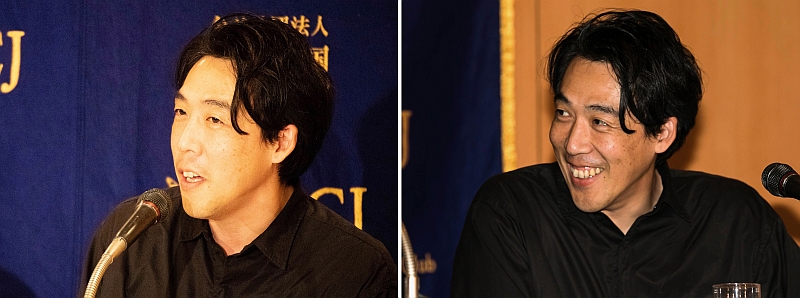

The directors were chosen for their visions, not their names. @Mance Thompson

Praising her fellow producers for Ten Years Japan, Eiko Mizuno Gray and Jason Gray of Loaded Films, who were also in the FCCJ audience, she explained: “We asked some 30 young filmmakers to submit a short synopsis and chose 12. We then discussed them with Mr. Kore-eda, and finally picked these five because their ideas and scripts were great, not because of their names or previous work. It was really important for Mr. Kore-eda and for us to take the time to discuss the scripts, and to mold the entire process to create one feature film.”

Kicking off the Q&A session following our sneak preview, a journalist noted that the molding process had yielded films of equally impressive quality, unlike the usual unevenness of most omnibus efforts. He wondered whether there had been any coordination or even collaboration between filmmakers during production to achieve such a uniform level of excellence.

Speaking for the group, Chie Hayakawa explained, “In August last year, all of us met and heard for the first time about each other’s projects. There was no coordination or even communication between us during the production process, so we heard each other’s concepts, and then we saw the completed films. That made it a really interesting experience.”

Although the five emerging filmmakers, appearing together for the first time in public since the completion of the film, received several specific questions, in the interests of fairness, here’s a brief rundown of the questions that were posed to all five. Responses appear in alphabetical order.

Akiyo Fujimura ra won the Skip City Award at the 2016 Skip City International D-Cinema Festival for her feature debut, Eriko, Pretended.

Left: ©Koichi Mori, Right: ©Mance Thompson

On how they selected their themes:

Akiyo Fujimura, director of The Air We Can't See, in which a disaster has driven the Japanese population deep underground, until one lonely girl finds a “place only kids can go”: “While I was thinking about my theme, I looked back on the past 10 years in Japan. What really stood out was the 2011 Fukushima disaster, and when that happened, there was a real fear of the air, which we can’t even see. I’d never imagined being afraid of the air, and it seemed a real likelihood that [a disaster like that suggested in the film] could happen within the next 10 years.”

Chie Hayakawa, director of Plan 75, in which longevity has become a liability in Japan, leading to a government-promulgated solution that targets the disenfranchised: “ My theme was inspired by our aging society, and the sentiment behind it was my anger at the way the disabled and the poor, society’s weak, are treated. There’s not a lot of room for them these days, and that made me very angry and lead to this film.”

Chie Hayakawa’s 2014 film Niagara won the Grand Prix at the Pia Film Festival as well as prizes from the Vladivostok International Film Festival and the International Women’s Film Festival in Seoul. Left: ©Koichi Mori, Right: ©Mance Thompson

Kei Ishikawa, director of For Our Beautiful Country, in which an adman (Taiga, in a standout performance) begins to rethink his job when he has to promote Japan’s remilitarization: “What I wanted to express was the freedom of expression. There was a Japanese painter, Leonard Foujita, who became a wartime [propaganda] painter during WWII, and that made me try to imagine how creative artists can be co-opted into the vortex of politics and the State in times of war or tumult. I thought that what would be most likely, 10 years from now, would be universal conscription.”

Kei Ishikawa’s feature debut, Gukoroku: Traces of Sin, premiered at the Venice International Film Festival in 2016 and went on to domestic box office success. Left: ©Koichi Mori, Right: ©Mance Thompson

Yusuke Kinoshita, director of Mischievous Alliance, in which children disrupt the 24/7 monitoring systems that control their every thought and deed, in order to rescue a dying horse: “When I received the offer to participate in the project, it was only 3 days after the birth of my son, and I decided to make the protagonist a 10-year-old boy. Since April this year, ethics was made a part of Japan’s compulsory education, and that made me think about what effect that would have 10 years from now. My own view is that it’s really difficult for children to learn ethics in a classroom setting. We can only find our own answers through action, and trial and error. I think that’s the way children should learn ethics. Neither teachers nor adults are perfect, so I feel dubious about our ability to teach through lecturing.”

Megumi Tsuno, director of Data, in which a young woman (rising star Hana Sugisaki) finds her mother’s digital inheritance card, and is able to connect with her past, which is a mixed blessing: “I know that the original Hong Kong version essentially focused on one political theme. But what I wanted to depict was the clear and present danger [of technology] that exists in our daily lives.”

Yusuke Kinoshita’s feature debut, Water Flower, premiered at the Berlin International Film Festival. ©Mance Thompson

On working with Kore-eda:

Akiyo Fujimura, director of The Air We Can't See: “I received advice from Mr. Kore-eda several times during both scriptwriting and editing. What made me especially happy is that he took the trouble to watch our previous films. He commended certain aspects that he liked, and gave me advice about how I could’ve improved it. That was a really good experience for me. He really respects the creative process and each director’s style. While following his advice, I realized it was steering me in the direction that I’d wanted to go in the first place.”

Chie Hayakawa, director of Plan 75: “He would always say to us ‘You are the directors,’ and I felt a real respect from him, that he was treating us as equals. He was never didactic in the way he related to us.”

Megumi Tsuno joined Bun-Buku in 2015, under acclaimed directors Hirokazu Kore-eda and Miwa Nishikawa, and directed the making-of documentary for Kore-eda’s The Third Murder. ©FCCJ

Kei Ishikawa, director of For Our Beautiful Country: “He gave us a lot of advice throughout the scriptwriting and editing process. But what really struck me was that, after I’d completed my film, he said that when he gave advice and a director came back without changing their script in certain ways he’d advised, he interpreted that as a sign that the director was principled. So he wouldn’t give the same advice twice. My discussions with him were very different from my experiences with other producers.”

Yusuke Kinoshita, director of Mischievous Alliance: “I received his feedback on three drafts of my screenplay. Naturally, since he is also a wonderful filmmaker in his own right, he gave me feedback not only on how he thought the audience would interpret the film, but also in terms of figuring out exactly what my own intentions were. When I first told him the synopsis, he asked me whether or not it had a happy ending. It really didn’t occur to me to look at it either as a happy or sad ending, and it was a challenge for me to figure out what I really wanted to say as a filmmaker.”

Megumi Tsuno, director of Data: “[As a staff member at Kore-eda’s own production company] I’ve had the fortunate experience of working with Mr. Kore-eda on set, and what always struck me is that he would continue writing and rewriting his scripts until just before shooting. Sometimes he would arrive on set and say, ‘I just thought of something in the taxi, so I’m going to change this part.’ I know it’s really daring for an inexperienced filmmaker like myself, but I’m afraid I did the same thing, and made changes until the last minute.”

On whether they felt any constraints on their creative self-expression:

Akiyo Fujimura, director of The Air We Can't See: “As a child, I didn’t enjoy studying. I was a film buff from my earliest years, and through cinema, I learned about the history of Japan and of the world. For instance, watching The Grave of the Fireflies taught me that war is something we should avoid at all costs. I think film can teach us about the world in the same way that school can, and it would be great if we could see films depicting more political and social issues. I hope I can continue incorporating them into my feature filmmaking.”

Chie Hayakawa, director of Plan 75: “Of course there isn’t any censorship in Japanese filmmaking, so we should be free to depict any theme we want. However, I do sense a kind of self-censorship when it comes to film companies and investors. They’ll say, ‘Well, that topic is hard to fund.’ I heard from the producers that this project was difficult in that sense. But it gave us a lot of confidence that it was a pan-Asian project, and that other filmmakers in other countries were also making films.”

Kei Ishikawa, director of For Our Beautiful Country: “I don’t think Ten Years Japan is overtly political, at least not compared to the Hong Kong version. But perhaps this fact, that we five all drew the line, reflects the current state of our country. It’s unnatural, the way that [other filmmakers] are avoiding depictions of these issues. I think there could have been more [hard-hitting] films about the Fukushima disaster, but there does seem to be self-censorship surrounding this country. So against that backdrop, I think we should be grateful to be given this platform to freely create.”

The omnibus directors applaud the audience following their first joint appearance.

©Koichi Mori

Yusuke Kinoshita, director of Mischievous Alliance: “I’m so grateful to the producers and to Mr. Kore-eda for offering this platform to create original scripts and original films. What instigated my film was the idea that I don’t think politics are separate from ourselves, they’re not ‘the other side.’ We have to consider ourselves part of politics, and when we do, that sentiment can change the system. I hope audiences who see my film will feel that way and help instigate change.”

Megumi Tsuno, director of Data: “I realize the difficulties that result from trying to depict political issues in film, including funding difficulties. So I was really thankful to participate in this pan-Asian project, to have the opportunity to create my own original script, and to be able to make my film without any limitations. I think it’s quite a revolutionary platform, and I’m so grateful to be part of it. Going forward, what I really want to do is to depict human stories. So I think it’s inescapable that politics and society will appear in the background of my films.”

The team with the Japanese poster for the film. @Mance Thompson

Ten Years Japan had its world premiere at the Busan Film Festival in October, where the three “franchise” films played together for the first time. Audience reactions were diverse, as they are for any omnibus project. But it’s clear that there is a future for this type of cinematic exploration, especially as the world continues its swing to the right.

©2018 “Ten Years Japan” Film Partners

Posted by Karen Severns, Thursday, October 18, 2018

Selected Media Exposure

- 73 年の歴史ある日本外国特派員協会での最後の映画試写会--日本映画界で描ききれないテーマに挑んだ 5 監督を海外メディア賞賛!『十年 Ten Years Japan』

- 「十年」石川慶ら新鋭5人が込めた“思い”、そして総合監修・是枝裕和監督からの助言

- 「十年」監督陣が是枝裕和との共同作業を振り返る「対等に接してくれた」

Read more

Published in: October

Tag: Ten Years project, Akiyo Fujimura, Chie Hayakawa, Kei Ishikawa, Yusuke Kinoshita, Megumi Tsuno, Hirokazu Koreeda, social issues, censorship, panAsian

Comments