Three long months after our last event, the Film Committee cautiously emerged from Covid-19 lockdown to host an intimate conversation with veteran film critic, festival advisor and cycling enthusiast Mark Schilling.

The small-town Ohio boy is now the world’s leading voice on Japanese film, with a catbird seat as a critic for the Japan Times since 1989. He has been the local correspondent since 1990 for Screen International and now Variety, is a cultural reporter for a wide range of international publications, and has authored six books on Japan, including the recently published “Art, Cult and Commerce: Japanese Cinema Since 2000.”

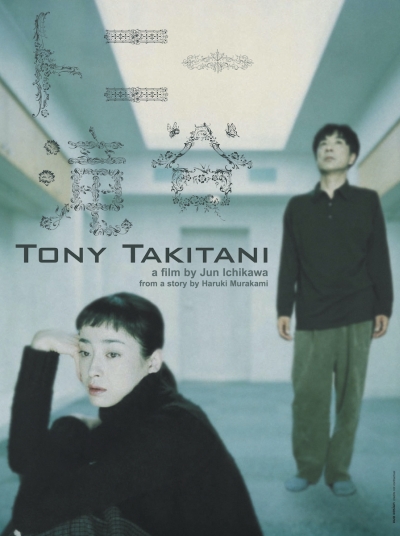

When we first approached him about joining us on the FCCJ dais, we suggested also screening a film of his choice. His immediate response had been, “something by Jun Ichikawa” — his favorite Japanese filmmaker, who had died in 2008 at the age of 59. With the assistance of Ichikawa's widow, Sachiko, we were able to treat the audience to a very special screening of the director’s 2004 masterpiece Tony Takitani, based on a Haruki Murakami short story. A delicate, haunting film shot in luminous near-monochrome, it beautifully renders the spiritual isolation of its eponymous protagonist, as well as of modern Japan.

© 2005 WILCO Co., Ltd

Introducing the screening, Sachiko Ichikawa shared a statement her husband wrote after he’d finished the film, highlighting his “attempt to answer demands brought about by Murakami’s literary world, which may be solid but is nonetheless floating a few centimeters off reality’s ground;” and of his own conviction that the film version should have “shots comprised of blank spaces like Edward Hopper’s paintings.”

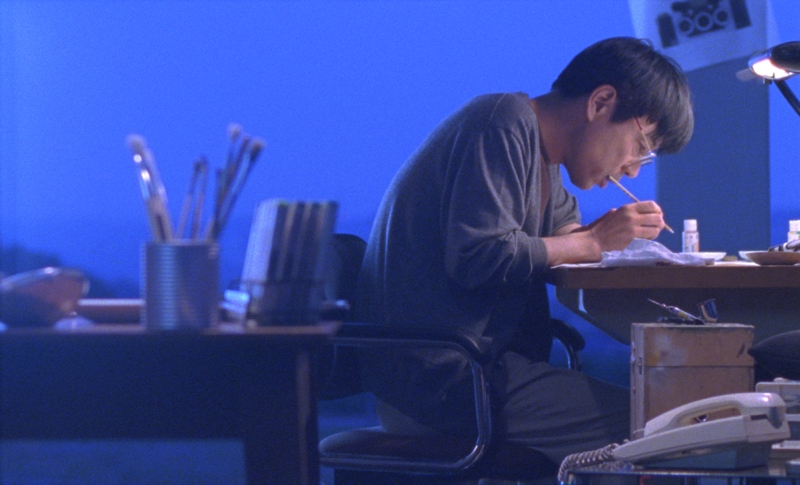

The director’s longtime collaborator, acclaimed photographer Taishi Hirokawa, the award-winning cinematographer of Tony Takitani, told the audience Ichikawa wanted the film to feel as if “viewers were turning the pages as they read the story,” resulting in the camera’s subtle, ceaseless movements from left to right. He also recalled how they had had just two weeks to shoot, and had built all the sets in the open air on a hillside near Yokohama, despite the imminent typhoon season. “But Ichikawa was always lucky,” he said. “The rains skipped us.”

Settling in for a long, genial chat after the screening, Schilling was asked why Jun Ichikawa is so important to him. “I didn’t know much about him when I first started reviewing in 1989,” he admitted, “so for me, the discovery was Dying at a Hospital [1993]. I went into the screening cold and I was totally blown away. You’re watching patients who are all being treated for cancer… and you also see people outside the hospital, doing ordinary things. That combination, of people who are going to die and people who are very much alive — the contrast just hit me so hard.

Hirokawa discusses building the open-air sets. ©Koichi Mori

“I ended up showing it at Udine (Far East Film Festival, where he curated the first international spotlight on Ichikawa’s work in 1994), and believe me, the last 10-15 minutes, everyone in the audience was [sobbing]. I couldn’t stop crying myself, and afterward, the director said, ‘I feel kind of sorry — I just make films that make people cry.’

“I ended up seeing everything he made after that, and he became my touchstone. This is why I’m doing this. At the time, there were up-and-coming directors getting attention, like (Takeshi) Kitano, (Hirokazu) Kore-eda and later (Kiyoshi) Kurosawa and (Naomi) Kawase. It was great for them, but I thought, ‘Wait a minute, Ichikawa should be up there with them. ’ He wasn’t being ignored in Japan, but I thought he could take a step up, beyond Japan, and I tried to do what I could. I thought, ‘This is my mission, to make his films better known.’”

©FCCJ

Asked why had he selected Tony Takitani to screen at FCCJ, when it was almost too good at making the audience feel “extremely isolated and lonely,” Schilling responded, “It’s the time we’re living in now, isn’t it? Mrs. Ichikawa shared her husband’s thoughts about Edward Hopper, who’s become the artist of the coronavirus era. When I first saw it, I remember thinking that maybe it wasn’t cinematic enough. But I watched it again, and everything fits together the way Ichikawa intended it to: the images, the music, the acting. For me, it builds up to that moment when Tony’s wife is gone and he’s alone in her closet, a huge room, with all her clothes. I’ve had that experience in my own life. Someone dies, you go in and see their things the way they left them for the last time. And you never forget that. You never forget the feeling you have, the smells. That sums up the absence you feel when someone dies. Tony Takitani works for me like a film but also like a visual poem.”

© 2005 WILCO Co., Ltd

Here, with ellisions, are other highlights of our conversation:

On selecting the reviews, interviews and essays included in his new book

The last time I did this was for the 1999 book “Contemporary Japanese Film,” which collected articles I wrote for the Japan Times from 1989. The publisher for that told me, “If you want to include all these reviews, you’re going to have to cut them down. They’re too long.” So I spent about a month and it was agonizing. I kept thinking, “Did I really write that?” This book wasn’t as bad. At the beginning of the millennium, I had about 1,200 words to play with. Now I have 550. It forces you to compress your thoughts, but it’s not quite enough. Every time they cut me down, I was fighting for the word count. Now I realize maybe it’s not so bad.

On whether his opinion of some films had changed since writing his initial review

Sometimes I see films after a long time and realize, “I liked this too much the first time around,” or I see something in it that I didn’t see before. That was the case with Tony Takitani, since when I first saw it, I hadn’t had the experience of having someone close to me die. And then I did. Seeing it again, I realized it’s a very artistic, very minimal film. But it’s deeply emotional, too.

©FCCJ

I have to give stars for the Japan Times reviews, and I think I gave 5 stars to only a few films every decade. I look back on those and think, “I really shouldn’t have done that.” (Pushed for examples, he finally relented.) There’s one called Sakuran, based on a manga by a woman, directed by a woman, starring the great Anna Tsuchiya, with a brilliant score by Ringo Sheena. I saw it and thought it was the ultimate feminist film. Women had been working so hard for so long to make any mark in the industry here, and it seemed like this was the breakthrough. I thought about it afterward. Really 5 stars? Maybe not.

On who will supplant the 4Ks (Kitano, Kore-eda, Kurosawa, Kawase)

They’re all over 50, and the ones coming up behind them, Koji Fukada and Miwa Nishikawa, are in their 40s. So they’re not young, but they’re ready to take the step up, too. Fukada’s new film was just selected for the Cannes 2020 label. I really like Shuichi Okita. We’ve shown six of his films at Udine, and every one has been a hit. He’s on the verge of a breakthrough. Shinichiro Ueda, director of One Cut of the Dead, is another one. We gave that film its world premiere at Udine, and it’s made more than 1,000 times its budget at the box office.

On film(s) he wishes had gotten greater attention

Jun Ichikawa’s, of course! And Nobuhiko Obayashi’s. He became famous abroad for House. I first discovered him in 1989 with Beijing Watermelon, about Chinese students in Japan. He was going to shoot in China but Tiananmen prevented it, so he just made a mock-up of an airplane and shot everything here. He plowed right ahead. I thought, this guy’s got balls and imagination. The last film he made before he died, Labyrinth of Cinema, a film made by a dying man [Obayashi had terminal cancer], had more energy than many, many films made by people healthier and younger, but not as brilliant as he was.

© 2005 WILCO Co., Ltd

On which director has gotten too much attention

I mean, really, Japanese directors don’t get that much attention. Even someone like (Hayao) Miyazaki, when he started going abroad, Harvey Weinstein wanted to release Princess Mononoke as an arthouse film. It was so huge in Japan, and in the circle of overseas anime fans, but it just didn’t get out to a wider audience, compared with Pixar or Disney films.

On how he decides which films to review

It’s always difficult. I’ll look through all the upcoming films, watch the trailers, spend a day on that. Sometimes I think, “Oh, jeez. My time on earth is limited!” I’m at the point now where I don’t want to see a film I know I’m gonna hate. Very often the upcoming films are by directors I really admire or young directors who seem interesting, and I’ll [choose that way]. That’s only 4 films a month out of how many? Over 600 Japanese films were released last year, and I can’t cover them all. We have another couple of reviewers now, James Hadfield and Matt Schley, who’s covering all the anime. Thank god I have help.

On how much his own experience influences his choices of ‘good’ films

The famous critic Manny Farber once said, paraphrasing, “The critic watches the film, but the critic is also a man.” I don’t try to hide that. If something connects with me on a personal level, I mention it. One example is watching Koji Fukada’s Harmonium. That’s one of the greatest films [in a long time]. There’s a scene when the character played by Kanji Furutachi goes into the river to try to rescue his daughter. He comes out and he freaks out. If I’d seen the film without knowing anything about the situation, I might’ve thought he was overacting.

©FCCJ

But I have been in that situation, way back 40 years ago in my hometown in southern Ohio. I was on my bike, and a motorboat overturned. I’m a trained lifeguard, so I jumped in and swam out to the boat. People were screaming, “Get the baby! Get the baby!” and pointing to the water. It was very murky, I couldn’t see 2 feet in front of my face. I couldn’t find the baby. Then this teenager who was trying to help started drowning, so I went over to him. Finally, they brought the grandmother [who’d been holding the baby] to the shore, and she was just screaming and screaming. I thought, “She’ll never recover.” For whatever reason, Furutachi understood this. His character will never, ever be the same. And he gets that.

On documentaries

I write on documentaries when I can, when one is so important for some reason. Kazuo Hara just did one, Reiwa Uprising, about an election last year. It’s 4 hours long, and I sat, transfixed, throughout the whole thing. He’s someone who can do that to me. He also did Sennan Asbestos Disaster, and he spent years putting that together. He’s trying to be objective, but he has a point of view. He’s trying to get under the surface. He’s not really the friend [of the film’s plaintiffs], he’s making a film and he’s going to do what’s best for the film. For me, Hara’s work is equal to or better than what anyone’s doing in fiction films.

On whether his interviewing style has changed over the years

Interviews used to really intimidate me. I couldn’t sleep for days beforehand. Somehow, I got over that. My strategy was to read as much as I could about the person, see the film, but not write up questions until I was on the train to the interview, after everything percolated in my head. I have this scribbled question list with me like a safety blanket, but I never look at it because my objective is to start a conversation. A lot of directors have a script in their head, they’ve prepared what they want to say and they’re gonna somehow get it in there. So my strategy is to have a conversation and get them off script.

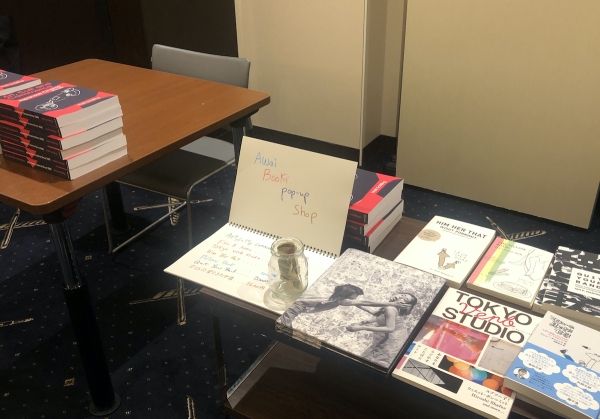

Schilling's new book, left, and others from Awai Books. ©Koichi Mori

On Donald Richie’s influence

Donald Richie was my friend and mentor for about 20 years. He really encouraged me when I first started out. I could never repay him. We would go to movies together and talk about them afterwards. To hear the voice of Donald Richie is like hearing the pronouncement of God. He had no doubts about what he thought about a film. He lived in Ueno, in this little apartment overlooking Shinobazu Pond. He would invite me over to eat dinner and watch films. He had this collection of DVDs, all great films, and he would suggest titles. I’d say, “Hmmm, how about this one?” And he’d say “No, we’ll watch this.” He had this tiny TV sitting in his oshiire closet, which he used as a monitor, and he’d put in a DVD. All he had to sit on were straight-backed chairs. I thought, “I can’t slump, I can’t sleep, I’ve got to pay attention! Donald Richie is here! We’ re watching this together!”

Watching with him, in the privacy of his apartment, I paid attention to every frame. He gave me that gift of attention. I’m still pretty degenerate in the way I watch some films, but one worth paying attention to, it’s worth paying attention. I always end up with 10, 12, 15 pages of notes about everything from the story to the editing to the camerawork. I wasn’t trying to be Donald Richie, I was just trying to hold my own in the conversation. So I had to bring my best game. That’s what he gave me.

For more anecdotes, as well as reviews, essays and interviews spanning the past 20 years of Japanese film, see Mark Schilling’s “Art, Cult and Commerce: Japanese Cinema Since 2000” (Awai Books, New York and Tokyo).

Posted by Karen Severns, Saturday, June 27, 2020

Read more

Published in: June

Tag: Mark Schilling, Jun Ichikawa, japan times, Variety, Udine Far East Film Festival, Koji Fukada, Kanji Furutachi, Shuichi

Okita, Nobuhiko Obayashi, Shinichiro Ueda, Kazuo Hara, Donald Richie

Comments