The innocent man wrongly accused, fighting for the elusive truth that will free him: it’s a familiar theme in literature and film, and it seems unlikely to ever wear out its welcome.

It’s somewhat surprising, then, that Franz Kafka’s great existential nightmare, “The Trial” (“Der Process”) has been filmed only twice before. The first time was in 1963 by Orson Welles, who set his expressionist interpretation against the backdrop of the Cold War; the second was in 1993 by David Jones, who returned the story to its Prague roots, giving it a less overtly contemporary subtext.

John Williams, a Welshman who has made his home in Japan for several decades, has now transplanted the tale to Tokyo, and the great accomplishment of his adaptation is that it seems both absurd and yet frighteningly plausible.

Williams, flanked by Niwa (left) and Tsuneishi (right). ©Mance Thompson

Williams’ day job is teaching literature and film at Sophia University, and his earlier Japanese-language films reflect his fluency with richly layered texts. In 2016, he found inspiration for a radical reimagining of Shakespeare’s “The Tempest,” set entirely on Sado island (and aptly named Sado Tempest), fusing Noh theater, taiko drumming, Japanese rock and time travel. His 2006 Starfish Hotel (taglined Welcome to the Darkland, and perhaps inspired by both “Alice in Wonderland” and Haruki Murakami), was a supernaturally tinged tale of a salaryman searching for his missing wife with the help of a man-size rabbit.

The writer-director has previously discussed The Trial as a reflection of Japan’s current political climate, citing the government’s attempts to “clamp down on divergent voices and opinions, actively muzzling the media and passing laws that threaten journalists’ freedom. People who want to see [the film] as a satire about Japanese bureaucracy can read it that way too, but it is also a film about the education system or about the problems of a society where people mostly sleep their way through the systems that govern their lives and are persuaded by the government and by TV and by the media not to think too much and not too think too deeply. I worry that democracy is being slowly whittled away by something far more insidious than the Japanese government, and that ‘something’ is so subtle it is almost invisible most of the time.”

Niwa, left ©FCCJ; Tsuneishi ©Mance Thompson

Appearing at FCCJ with the two stars of The Trial, Williams explained, “Originally I was going to shoot a lot of the film in a very unreal space in a very unreal way. But I realized that I wanted to make a film about contemporary Japan, and I was really only using ‘The Trial’ as a commentary on contemporary Japan. Therefore, to make a surreal version of it would blunt the impact of what I was trying to say. Part of what I was trying to explore was the creeping sense of things becoming unfamiliar and strange in the world of Japan today, and the only way to do that was to find concrete examples in the real world, but shoot it in a real world that is somehow defamiliarized.”

Indeed, the “real world” of the film is completely recognizable, yet austere, washed of intense colors and depopulated. It opens in a nondescript apartment block, where Yosuke Kimura (Tsutomu Niwa), a banker, has awoken on the morning of his 30th birthday to find two men at the foot of his bed, announcing he is under arrest. When he demands to see the warrant, they admit they haven’t been entrusted with it, but will instead be his “angels.” Kimura has no idea what the charge is, and when the official warrant arrives later by special delivery, it stipulates no crime. His comely next-door neighbor, Mari Suzuki (Rino Tsuneishi) has just dropped by to say the angels questioned her about him, and she urges Kimura to confess. He assures her he is innocent. She finds his apartment a bit too tidy, but he does seem mild mannered…surely he’s no criminal.

Yosuke Kimura (Niwa) awakens to an existential nightmare in John Williams' The Trial.

©Carl Vanassche

Kimura is summoned to a court date by the National Security Council Court Office, but with the wrong address and no time. When he manages to arrive, he finds a ridiculous scene: the apparent chief clerk sits at a desk in a school gymnasium, as a woman hangs underwear on a laundry line strung behind him. When Kimura dares to suggest that things are simply not right in “this farce you call a court,” the hearing is halted and he is ordered to return later. On his next court date, he finds a roomful of fellow offenders, some of whom have awaited trial “for an eternity” and urge him not to be rash.

Mari offers to give him an alibi, but flees when he tries to kiss her. The court laundry lady (Shizuko Kawakami), a self-professed legal expert, seductively suggests, “We could add testimony to your file to help you. We could lose some of the incriminating testimony.” But whenever Kimura accepts help, or engages in harmless flirtations, he looks even guiltier. Eventually, even his lawyer despairs. “You need to control your lust,” he shouts. “Your sloth, your avarice, your pride, your sexual deviance! How can I defend such a monster?” Wherever Kimura turns, people seem to know about his trial — worse, they all believe he’s culpable and will face a terrible punishment in the end.

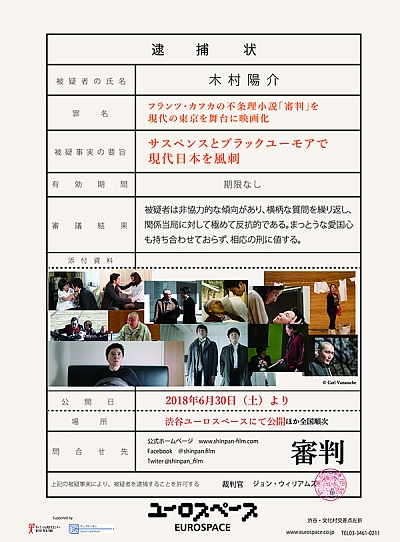

The back of the Japanese flier for the film is a clever

approximation of Kimura's court summons. ©︎Carl Vanassche

In the park one day, he finds a puppeteer putting on a show with the Crow Man, the “only law,” who “comes out of the darkness” to rule over the world, finding all the “bad, rude, greedy, lazy” people… the criminals.” As the children in the circle around the puppeteer giggle, he turns to Kimura, and advises him to simply accept the inevitable: “Haven’t you heard that Truth is dead? Everything is just a big show nowadays.”

The Trial is rife with such pointed criticisms, and Williams’ actors were asked whether they had hesitated to take part in what could possibly be considered a seditious work.

Photo left ©Mance Thompson; right ©FCCJ

Niwa, who appeared in the director’s previous three films and assumes his first leading role with The Trial, responded in English, “We first collaborated together on his first film, Firefly Dreams. We’ve worked closely since then for [almost] 20 years, so I didn’t hesitate to put my trust in him. I understand his style, and what he envisions for his films. But it was hard to prepare for this role. I couldn’t define a thruline for the character. It was a struggle for me. I knew he was just passive, but it would have been boring if I was acting only passively. What finally clicked for me in finding the character was the death of my father-in-law. I realized that the character represented the entire life of a person. As I took care of my father-in-law and watched him fight to live on, his struggle was the same as this character’s.”

Tsuneishi also professed full faith in her director: “I personally agreed with [Williams’] commitment to depicting what he wanted to depict, and it’s up to each individual viewer to interpret the film in their own way. I thought it was a good opportunity to participate in the film, because by portraying these problems, it can instigate discussion.”

Court is in session. ©Carl Vanassche

Pressed further about the overall message, Williams replied, “I don’t want to be too specific about what political meanings I intended, because I do want it to have multiple interpretations, and I did want to be true to Kafka’s existential novel. I hope it’s a film not just about politics. As Tsutomu said, each one of us has to make sense of our own lives. I suppose something that really stuck in my head was, about three years ago at Sophia University, while we were doing a critical thinking exercise about a piece of literature, one of my students asked, ‘What is the answer to this?’ I said, ‘Well, I don’t have an answer. It’s literature. What does it mean to you?’ She said, ‘No, the teachers in our schools have a book which gave all the answers for each piece of literature. I want an answer. I want you, as a teacher, to tell me what it is.’ I began to feel that a lot of young people were in a similar mind frame, that there’s a right answer and it’s going to be given to you by somebody else. So partly, this film is a critique of that — who thinks our thoughts for us? I suppose that’s both a philosophical and a political question.”

Thanking Williams warmly for “another head-scratching film,” one attendee asked whether the #MeToo movement, with “men seeing women as sexual objects or feeling that they’re guilty without being charged,” had had any impact on his approach. The director explained that the shoot had actually taken place in February 2017, and the movement “really kicked off slightly after that. Of course I was thinking a lot and talking a lot with the actors about the sexual politics of it. I could see the potential for Kimura being a kind of James Bond character who goes through a load of women who all appear to be in love with him. In the book, a couple of the women characters are like victims, and I wanted to strengthen some of them, give them an empowerment — but a false empowerment. Last year I spent time back in Britain, and when I came back I was really shocked at how different the gender politics are here, how women are not respected. I was trying to say something about that.”

©Mance Thompson

Asked to clarify whether the focus on women trying to seduce Kimura was present in the original novel, Williams responded, “It is in the original novel. The women all claim that there’s a special aura he has because he’s [been] accused, and there’s a lot of sex and sexual behavior in the novel. But I wanted to try to suggest that women in Japanese society are trapped in this role where they have to use their sexuality because they’re deprived of real power. I was trying to suggest that these characters are all in a state of false consciousness about how to use power in society. My wife told me that I wasn’t successful in doing that [laughter]. But the intention was to preserve the thing in the novel about sex is power, but to try to depict four different types of women who are all using their sexuality, but not in a way that is actually genuine. I talked a lot to the actresses about this because I was aware that this is a kind of dangerous area.”

Said Tsuneishi, “I think the female allure or attraction depends on the woman and the power that she has. Whether it applies only to Japanese women, I don’t think that’s necessarily the case. As for the four women in the film, they each use their own approach to seducing Kimura. I agree with what [Williams] said, but when it comes to my own role, although Mari wants to figure out how to use her sexuality as a means of power, I don’t think necessarily all women are like that. One thing that isn’t depicted in the film is that Mari is actually a virgin, so she’s actually very timid and she craves physical contact, but she’s too shy. She wants to break out of the box she’s confined in.”

The Crow Man delivers a frightening message. ©Carl Vanassche

She continued, “As for the depiction of women and how they’re perceived, I think this is something that is true of other countries as well as Japan. I get very aggravated at times by how women are perceived. But I thought that if the director wanted to create an opportunity for discussion, there was no reason not to participate. The script was written in English and translated, but the director was very inclusive and we discussed how to re-translate certain words and phrases. He was very considerate in that way.”

As for Niwa, whose character is chided by a priest for “looking for help in all the wrong places,” he said, “For Yosuke Kimura, all four women helped him, and he wanted their help. They’re the keys to saving him, and saving his life.” He laughed bitterly. “But they didn’t save him.”

©Carl Vanassche

Posted by Karen Severns, Friday, June 29, 2018

Selected Media Exposure

- 『審判』記者会見@日本外国特派員協会

- にわつとむ 外国人記者の質問に英語ジョークで切り返し

- 「審判」を現代日本で映画化、FCCJ会見

- フランツ・カフカの不条理文学を原作を使って、現代の日本をコメンタリー ジョン・ウィリアムズ監督『審判』-日本外国特派員協会で会見

- ジョン・ウィリアムズ監督の『審判』、現代の日本が舞台!

Read more

Published in: June

Tag: John Williams, Franz Kafka, existential nightmare, political dissent

Comments