The announcement for this sneak preview screening began, “You may not have heard of Michio Kimura, but after seeing A Voiceless Cry, his is a voice you will never forget.” As it transpired, no one in the audience had heard of Kimura before; but there was unanimous agreement afterward that his voice should be heard.

Admittedly, hearing his words read by the great Butoh dancer-actor Min Tanaka is one of the film’s highlights. During the Q&A session, director Masaki Haramura explained the serendipity that enabled his vocal presence: “Min Tanaka’s teacher, Tatsumi Hijikata, played the role of a farmer from the Edo period in Shunsuke Ogawa’s final film, The Sundial Carved with a Thousand Years of Notches,” he said. “Mr. Tanaka is himself a farmer, who has been living for decades in Yamanashi Prefecture in the belief that the roots of dance lie in the physical gestures that came out of the agricultural lifestyle. He was eager to go to Yamagata someday, and knowing that Michio Kimura was the man who brought Mr. Ogawa to Yamagata only enhanced his desire to go. When I asked him if he wanted to be a part of this film, he was so excited that he offered to read the entire narration. But we felt that would be too much.”

Haramura then offered an eloquent summation of the symbiotic relationship of land to culture: “I believe that Mr. Kimura came to the arts through agriculture,” he said, “and Mr. Tanaka came to agriculture through the arts.”

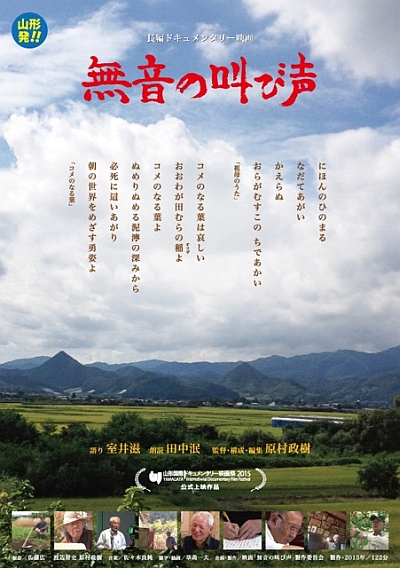

An elegy for Japan’s agrarian past, when its villages were the lifeblood of the nation, A Voiceless Cry takes us deep inside the world of Michio Kimura, a celebrated poet who is the recipient of a handful of Japan’s most prestigious prizes, but also a rice farmer, an ardent antiwar activist, a devoted family man, a cancer survivor, a patriot and a rebel. Now in his 80th year, he continues to vigorously “cry out on behalf of voiceless farmers everywhere,” demonstrating a mastery of the agrarian idiom, penning powerful free-verse poetry that decries a vision of nation that does not pursue a peaceful future.

Born in the tiny community of Magino, Yamagata Prefecture, Kimura was initially driven to write by the loss of his father during World War II. After high school, he helped form the farmer-poet collective that published the Chikasui (Groundwater) anthology, which continued until 2014. When Japan’s rapid economic growth in the 1950s began draining farming villages for the cheap labor sources they provided, Kimura joined thousands of other farmers on the crews that built Tokyo’s highways and skyscrapers. For a decade, Kimura would spend half the year in construction, half in farming. But he learned that his heart belonged on the farm in Magino.

Michio Kimura, man of many voices ©2015 “A Voiceless Cry” Production Committee

A participant-witness to the most important protest movements of the past century, he rallied against the rice-reduction program, the Japan-U.S. Security Treaty, Narita Airport and the Agricultural Basic Act, which sought to implement Big Farming. During China’s Cultural Revolution, Kimura joined a work-study tour; in the 1970s, he went to Wake Island to recover the remains of his uncle and other Japanese soldiers who had died there of starvation. After documentarian Shinsuke Ogawa spent years filming the protest movements against Narita Airport’s construction, Kimura invited him to visit. Ogawa’s group then lived and farmed (and filmed) in Magino for the next 18 years, creating several masterpieces of village life, exploring the convergence of farming, modernization, state violence and rural resistance.

Not surprisingly, the first question asked during the Q&A following the screening of A Voiceless Cry concerned the looming passage of the Trans-Pacific Partnership deal in the Diet. The TPP free trade agreement will impact not only Japan’s 1.5 million farmers and agri- product makers, but also its manufacturers of textiles, industrial goods and automobiles.

©Koichi Mori

The questioner, a Todai research fellow, began with a brief recap: “The Japanese government has asked all the prefectures to estimate how much money will be lost in agricultural production, and they’re estimating ¥130 - ¥210 billion [$1 - $2 billion] every year… Obviously, this will accelerate the depopulation of the countryside. I’m curious whether people are talking about this in the countryside. What does Kimura-san say about it? How did you decide to not talk about this in your documentary?”

Said Haramura, an award-winning documentarian, “I’ve been working with farming communities for over 30 years as a filmmaker,” he began, “but I’m not a journalist or a scholar, so I don’t feel that I’m in a position to respond directly to [the TPP issue]. I can tell you that Mr. Kimura, although he does have an opinion about TPP, is not involved in social activism directed at TPP.” Explaining that he wanted only to document Kimura’s past and his present activities without injecting his own anti-TPP stance into the story, the director continued, “Of course Mr. Kimura is also against the TPP, and I would say that across the country, people working in the primary sector [agriculture, forestry, fishing, mining] are 90 percent opposed to TPP.”

But he cautioned, “Aside from talking about the importance of agriculture, I think we should be more critical of what TPP does to regional economies. The sustainability of regional economies is critical for Japan’s future.”

The villagers of Magino protesting in the 1970s. ©2015 “A Voiceless Cry” Production Committee

Another question, from a Yamagata native who said he was struck by the “spiritual richness” of the farmers’ lives, concerned whether Yamagata is different from other prefectures. The director replied: “The area where Mr. Kimura lives is a village where, when the government started its policy in 1970 of gentan — essentially subsidizing farmers for not farming — the locals decided to have alternative means of employment, like working for the agricultural cooperative or the village office… On the surface, it may seem that there is no culture in this hamlet, and when I started the film, I didn’t know what the other villagers were doing. But after meeting and talking with about 30 of Mr. Kimura’s neighbors, gradually I discovered all the treasures of history that they’ve continued to preserve. I feel that, in every place you go in Japan, the more you talk to the locals, the more you realize how these regional communities are thriving, each in their own way.”

“Although he’s an intellectual,” Haramura said in closing, “[Michio Kimura] always says that he’s been writing poetry with his body, not his brain,” “If you read his work from the time he was a teenager until his 80s, the 60 years of history represents not just his own life experiences, but the history of postwar Japan, seen through the eyes of a villager. That was one of the strongest motivations for me to make this film. I feel that the values of Japan’s villages reflect not only our postwar past, but also our future.”

A veritable primer on rice farming, as well as a richly illustrated archival history of Japan’s destructive agrarian policies and the carving out of its villages, A Voiceless Cry is essential viewing for all those who make Japan their home, or their subject.

— Photos by Koichi Mori.

©2015 “A Voiceless Cry” Production Committee

Posted by Karen Severns, Sunday, April 03, 2016

Read more

Published in: March

Tag: Michio Kimura, Min Tanaka, Shunsuke Ogawa, Masaki Haramura, antiwar, Yamagata, awardwinning

Comments