There are few FCCJ members who don’t remember our overflow screening of Louis Psihoyos’ The Cove in 2009, the first Japan showing of the now-infamous documentary that depicted, in gruesome detail, the annual dolphin capture and slaughter in the tiny village of Taiji, Wakayama Prefecture. The film would go on to win the Oscar for Best Documentary, and to have an enormous impact on international public opinion regarding Japan, creating an Us vs. Them mentality, pitting environmentalists against traditionalists, and allowing no space for a dialogue to develop.

Encouraged by social media-savvy activists, protestors began pouring into Taiji every September during hunting season for the next 8 years. The swarming presence of angry outsiders, and their frequent verbal attacks on fishermen — who had been vilified in The Cove — compounded the travails of locals and exacerbated any chance for a rapport. With the rallying cry on both sides reduced to a too-simple pro- or anti-whaling stance, the situation soon devolved into cultural warfare.

Yet their efforts did not put an end to the dolphin cull — or to whaling, although most Japanese eat neither dolphin nor whale meat.

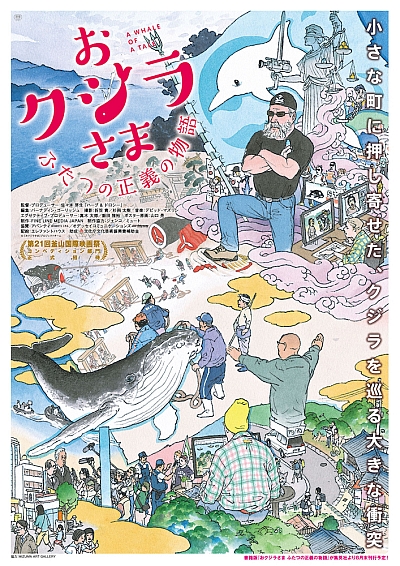

Onto this battleground stepped New York-based Megumi Sasaki, who followed the protests in Taiji for 6 years, and has created what is perhaps the first unbiased, nuanced portrait of the ongoing controversy. Rather than recreating the tense drama of The Cove to provide a Japan-defending “corrective,” she set about capturing the current reality on both sides of the yawning divide. Sasaki’s resulting A Whale of a Tale does not issue a call to action, but rather, to understanding.

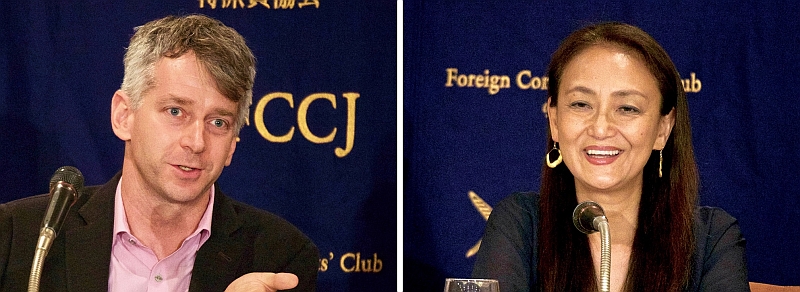

Both ©Koichi Mori

The film is quite different from Sasaki’s first two theatrical features, both of which she brought to FCCJ, the award-winning Herb & Dorothy (2008), about legendary New York art collectors Herb and Dorothy Vogel, and the follow-up, Herb & Dorothy 50X50 (2013). Drawing on her years as a news reporter and field producer for NHK and other Japanese broadcasters, Sasaki was able alight with confidence in Taiji, and to develop relationships of trust with both the fishermen and the activists. (Alabaster calls her "a force of nature" and lauds her interpersonal skills; Sasaki chalks it up to "a lot of shochu.")

In the Q&A following the screening of her documentary, Sasaki explained, “I saw The Cove in New York and I was really surprised at how it portrayed [Taiji]. It seemed to be extremely one-sided, without any understanding of Japanese ideas about nature and the relationship between people, nature and animals. Living in New York for almost 30 years, I always wondered why [the Japanese] always just show one side of issues. In the US, we always see both sides, whether it’s gun control or abortion or any other issue — except the whaling issue.

“When I saw The Cove, I felt like I needed to make a film. It stuck in my throat like a little fish bone, as the Japanese expression goes. Documentary can be very powerful and influential. It’s usually used to expose the wrongdoings of those in power: the government or the big corporations. But when the camera is pointed at the fishermen in a little village by a big Hollywood powerhouse, I didn’t feel that was fair at all. I thought their voices should be represented somehow. My intention was not to make a pro-whaling movie. Whether it’s right or wrong, I wanted to leave the answer to the audience."

©A Whale of A Tale Project

A Whale of a Tale begins by reminding us of the salient facts — many of which have become lost in the constant scuffle between the fishermen and the activists. Organized whaling began in Taiji, south of Nara, in 1606. For the fishermen, hunting is thus not only a way of life, but their very identity. Catching whales, dolphins and other fish has supported generations of families and fueled the town’s economy for 400 years.

For the activists, on the other hand, whales and dolphins are not fish but intelligent mammals, and they equate hunting them with the slave trade, fox hunting or bullfighting — all cultural practices that have been abolished or mitigated in modern times. As the fall hunting season begins, we see activists and news crews pouring in from abroad, wielding binoculars and cameras (sometimes quite violently) as they livestream footage of “atrocities” committed in Taiji, overwhelming the locals and the town’s infrastructure. Vans of right-wingers harass them via loudspeakers while others look on in dismay.

The film introduces us to the local whalers and several of the global protesters who have returned each year, including Ric O’Barry, head of the Dolphin Project and outspoken “star” of The Cove. But Sasaki’s wisest decision is to focus the film on the activities of two mediators who provide illuminating perspectives: American journalist and researcher Jay Alabaster, who moved to Taiji in 2013 and has devoted years to befriending and earning the trust of locals; and Atsushi Nakahira, a nationalist who taught himself English so he could communicate with the protestors. An unexpected peacemaker, he eventually succeeds in bringing the two sides together for a public debate.

©A Whale of A Tale Project

If A Whale of a Tale doesn’t quite turn us all into neutral observers, it moves us closer. Sasaki’s lasting achievement is that the film recasts the ugly ideological impasse as one of globalism vs. localism — something we can all understand, irrespective of background. Still, one of the documentary’s inescapable conclusions is that Japan would likely have banned whaling by now if foreign protests had not been so relentless and aggressive.

The film’s release couldn’t come at a better time: Just a week ago, as a new season was set to begin in Taiji, the Sea Shepherd anti-whaling group suddenly announced that it was suspending its protests against Japan after 12 years of disruptions, including those in Taiji.

But Sasaki pointed out that the protests had been decreasing already since 2015: “This is the third year in a row that we’ve seen very few protesters in Taiji,” she told the FCCJ crowd. “This is directly the result of local police efforts. They have been taking down passport numbers, and when the activists try to come back to Japan, they are refused entry. At least that’s what I heard. [We see this happening to Ric O’Barry in the film.] A lot of activists were there from the Dolphin Project and Sea Shepherd, but both groups have been having a hard time for the last few years. But it doesn’t mean that their activism has slowed down. They’ve had big demonstrations in front of Japanese embassies and consulates overseas, so they just changed their strategies.”

Both ©Koichi Mori

Joining Sasaki during the Q&A was Alabaster, the former Tokyo-based AP correspondent who was sent down to Taiji right after the release of The Cove and found his calling. He is now a Taiji-based PhD candidate at Arizona State University, and as we saw him doing in the film, he is continuing to help the fishermen boost their media literacy.

He emphasized, “Groups like Sea Shepherd are run like a business. They put their resources where they think they can get the most attention. So if they’re pulling out, then it’s because the attention they can get there has decreased a little.”

“We live in a world where people with access to the internet and social media have a louder voice,” said Sasaki. “We hear a voice, whether it’s right or wrong, and if it’s extreme, it reaches even further and sounds better to many people. But people with no access, like the fishermen in Taiji, their voice is diminished. We rarely hear from them. I think this is a very concerning issue.”

Alabaster interjected, “It starts with respect. Even if you disagree with someone, you can still respect them.”

©A Whale of A Tale Project

Continued Sasaki, “The world is becoming very intolerant. People tend to be mean and vicious, and easily attack one another online. Digital media has a lot to do with that. Anybody can raise their voice anonymously and find an audience.”

Mentioning the scenes of Alabaster showing Taiji locals how to use Facebook and Twitter, a journalist asked him about his vision for giving a more balanced view of the issue. “It doesn’t come off as fair to me,” responded Alabaster. “The protesters are media professionals. They’re very good at what they do, they have a lot of experience. If you’re going to have a debate, I think something should be said on the Japanese side. I’m working now on something — hopefully we’ll have it soon — a way for the fishermen to express themselves in English, to say where they’re coming from. I don’t know if you’ve been on Facebook, but there’s a pocket of it that is filled with hatred and meanness. If we can have a little bit more exchange of opinions, an online Q&A in English or a weekly blog with the fishermen, it could really help, for a start.”

One journalist in the audience, impressed that a “rightwing activist” in the film was acting as a negotiator, wondered about the position of rightists in Taiji.

“Nakahira is very unique,” said Sasaki. “He was the only person trying to communicate with the Sea Shepherd members. I was hesitant to talk to him at first, since [the nationalists] could cause trouble. But when I approached him, he was very friendly, made a lot of sense and emphasized the importance of dialogue. I thought he could be a good voice. We rarely hear what nationalists think in the conventional media.”

©FCCJ

Sasaki admitted that although she had set out to give the fishermen a voice on the international stage, “as I continued my research, there were many questionable practices from the Japanese side, for example, the government presenting this issue as one of tradition and culture. I was first trying to portray the bigger whaling issues: what’s happening with whaling in the southern oceans and Japanese research whaling, which have been targets of fierce criticism by the international community. But I discovered that what’s happening in Taiji is much more interesting — issues of why we cannot understand each other, why we cannot communicate, why we cannot respect other cultures. So I expanded the film’s themes to reflect what’s happening in the world today.”

She also noted, “One thing I found out about the meaning of tradition is that it’s very different between Japan and the West. For Japanese, tradition is extremely important. They believe that whatever has continued for a long time has to continue in the future, too. Tradition is valued heavily in Japan. In the West, as Scott West of Sea Shepherd mentioned in the film, just because it’s continued for a long time doesn’t mean it’s good, like slavery. If it doesn’t fit in today’s society, it should be abolished. That’s the Western way of thinking.

“For the people in Taiji, living with whales and whaling is their identity. It’s not just about food or economic activities, it’s their identity and their pride. I don’t think either side is right or wrong, it’s just a different approach … As former Mayor Goro Shoji says in the film, ‘Taiji has been and will always be living with whales. Depending on the time, we might catch them and eat them as food, or transform the city as an academic center for whale and dolphin research.’”

To a question concerning high mercury levels in dolphin meat, which was a major point of contention in The Cove, which highlighted how children are served “toxic” meat in school lunches, Alabaster commented, “Things will work themselves out [between the town’s existing factions]. Parents obviously want their children to be healthy. But when you add this incredible element of pressure, when someone who doesn’t speak any Japanese comes in and starts hammering, then those conversations have stopped within the town. If you complain [about dolphin in school lunches], then you’ll be grouped with the foreigners.”

©FCCJ

Sasaki added, “They’ve done a lot of research into the health effects of mercury, and we touched on that just a little in the film, reporting that the levels there turned out to be 4 times higher than the Japanese average. But none of the [townspeople] have suffered any health effects. The mayor was ready to give up the tradition if their health was damaged. But there were no health effects found in the adults, apparently because of the selenium, which appears to detoxify the mercury. In The Cove, they say these mercury levels are hidden by a media conspiracy, but no, it’s open information.”

As A Whale of a Tale makes clear even in its clever title, whaling is an issue that has been increasingly misrepresented. “I think it’s an issue of globalism vs. localism, not Japan vs. the West,” said Sasaki. “Global standards and values are clashing with local traditions and values all over the world. In Japan, [whaling] is causing nationalist sentiments, even though not every Japanese supports whaling or dolphin hunting. Only 30 – 40 grams per person per year of whale meat is consumed. So if you say that eating whale is Japanese food culture, it’s not correct.”

Alabaster summarized the ongoing controversy in terms that many of his fellow Americans could relate to: “The efforts of the whaling industry to survive and make itself relevant in Japan have been greatly aided by the Sea Shepherd. Everyone has their motivations, but if you went to any little town in America and without speaking English, told them to stop using guns, you would get exactly the same reaction.”

But Sasaki admitted that she doesn’t think the issue will ever quite go away. “It’s no longer an environmental movement,” she said, “it’s now become an animal rights movement, which is way more powerful and active.”

©A Whale of A Tale Project

Posted by Karen Severns, Friday, September 08, 2017

Selected Press Coverage

- Japan Cinema Now: Documenting the impact of The Cove

- Four Japanese films you should see this autumn

- 捕鯨、反捕鯨、両派を初めて描いた映画『おクジラさま』

Read more

Published in: September

Tag: Megumi Sasaki, Taiji, whaling, awardwinning, documentary

Comments