It’s an old saw, that artists are incapable of expressing themselves through language alone. When words aren’t enough, they pick up the tools of their trade… and speak volumes.

In David Neptune’s penetrating, lyrical Words Can’t Go There, a renowned musician does exactly that.

Starting off modestly, as befits its subject’s humble approach to his musical prowess, the camera follows a man in jeans as he arrives by truck, enters a bamboo forest, digs, chops and emerges with a small stalk. “I like to think of music as a bridge that can take you to a nameless, timeless place,” the man says, in voiceover, placing the stalk in his truck. “Words can’t go there.”

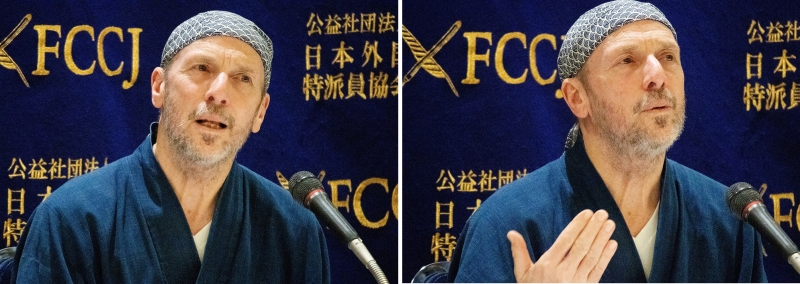

Hitoshi Hamada on vibraphone, John Kaizan Neptune on shakuhachi, David Neptune on take-da

and Christopher Hardy on percussion, a special live performance. ©Koichi Mori

A haunting tune of indefinable subtly and mystery fills the soundtrack. And suddenly, the camera lifts up and over the forest, taking flight as if the music has set it free.

Neptune’s film is, at heart, the story of a California surfer turned master of the shakuhachi (Japanese flute). But like all good stories about artists, it illuminates more than the process of creation.

Joining a select few films made by offspring about a famous parent, Words Can’t Go There was made by David about his father, John Kaizan Neptune, the most acclaimed non-Japanese practitioner of the shakuhachi, who has lived in Japan nearly half a century, recorded several dozen albums ranging from jazz, classical and traditional Japanese to world fusion, and performed across the globe.

Director David Neptune ©Koichi Mori

Every member of FCCJ’s sneak preview audience had heard of John, but few of us knew his backstory, nor the particulars of his arduous journey to prominence. The documentary rectifies that, and our screening was followed by an extraordinary live musical performance, with John on shakuhachi, Hitoshi Hamada on vibraphone, Christopher Hardy on an array of percussion instruments, and David joining in for the final tune on the bamboo take-da drum, which his father had invented.

Neptune elder and younger then joined us for the Q&A session, which began with what felt like a rite of passage: “It was very interesting to work with David, because he has so much more expertise in [filmmaking] than I do,” said John about the filming process. “That was a real eye-opener. Early on, we were friends as well as parents, going surfing or hiking or hunting for frogs together. Later, when he started working with film, he became a fellow artist, as well as someone who was fun to hunt for snakes with. So it was a nice transition, that we could (now) relate to the difficulty of making it as an artist.”

John Kaizan Neptune in concert. 2019 ©️ Ocean Mountain, LLC

The documentary traces those difficulties, but it isn’t until late in the film that the personal tolls really come into focus. Words Can’t Go There touches, quite movingly, on the sacrifices made by John’s wife and children while he was on the road half of every year, and on his own emotional distance.

A friend from Chiba, longtime FCCJ member John Harris, couldn’t resist asking, “Was it difficult to get Diane (Neptune) to participate? Some of the footage is really heartrending.”

Chuckling a little in discomfort, David replied, “It wasn’t hard to get her to participate. But it was probably my most difficult experience, asking her questions about her and my dad’s relationship. What child wants to ask their parents about what led to a divorce? She didn’t oppose being interviewed, but I think she was surprised by some of the probing questions that I asked.”

He went on to explain, “It wasn’t something I’d foreseen when I started the process. I thought, ‘Oh, I’m so impressed with my dad, with what he’s done, and I want to tell that story.’ But as I got into it and starting swimming upstream, I started finding all kinds of stuff that I felt I was obligated to explore. And that’s also thanks to the great people I worked with, like my cinematographer, Bennett (Cerf), who always prodded me to keep asking my parents more and more painful questions; and to (producers) Chiaki (Yanagimoto) and Mike (McNamara), who supported me throughout the process.”

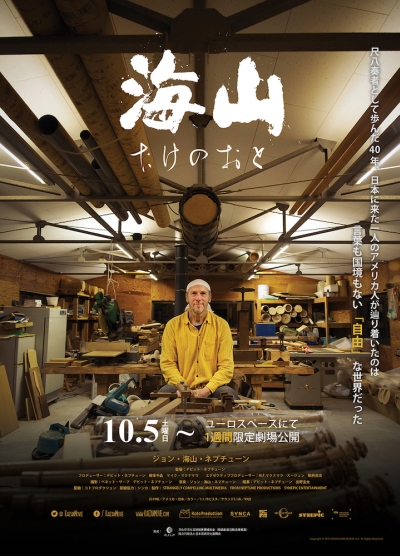

Neptune crafting a shakuhachi in his workshop. 2019 ©️ Ocean Mountain, LLC

The film traces John’s improbable journey from California to Chiba through a treasure trove of early photos and footage, as well as through interviews and performances with fellow musicians Kojiro Umezaki, Kifu Mitsuhashi, Kaaraikkudi R. Mani, Ghatam Giridar Udupa, Taizan Ohashi and Shinichiro Makihara. Family members recall that he had always driven himself hard. An early interest in the trumpet, inspired by his jazz trombonist father, gave way to an obsession with surfing, which led him to improve the surfboard by crafting his own, and finally, to enrolling in college in Hawaii so he could catch the best waves. While there, he took an Introduction to World Music class on a whim, and discovered the shakuhachi. It was love at first note.

In 1973, John moved to Kyoto to begin a rigid apprenticeship with grandmaster Genzan Miyoshi. A fellow student recalls that he would record their teacher’s playing on cassette, then “practice each phrase 500 times, 10 hours a day.” He was promoted to master in record speed, took the shihan name “Kaizan” (“ocean mountain”) and fled for the relatively free environs of Tokyo, where he could “do his own thing.”

That thing soon made him famous: John found his metier in the pioneering fusion of shakuhachi with jazz. Over the next decade, he appeared on innumerable TV shows, composed 80 pieces, released 10 albums in a variety of genres, and in 1980 — just 7 years after committing himself to a shakuhachi career — became the first-ever non-Japanese playing a traditional instrument to win Best Record at the annual Japan Record Awards.

John’s improvisations expanded the possibilities of the shakuhachi (“He’s someone who changed the game,” enthuses shakuhachi player Kojiro Umezaki, who performs regularly with the Silk Road Ensemble, in the film). Even as traditionalists criticized the achievement, John’s impact became increasingly global. As he’d done with surfboards, in his pursuit of the “perfect sound,” he also began crafting his own flutes, innovating them to create sounds never heard before, resulting in what aficionados dubbed the “turbo shakuhachi” for its large bores, and earning a reputation as the best tuner in the world.

©Koichi Mori

Asked whether other musicians do the same thing, John told the audience, “Players don’t make their own shakuhachi, but you have to play quite well to be able to make one because you’re shaping the bore to create the sound. If you can’t play well, you don’t know if it’s you or the instrument when you’re trying to improve the resonance. But the reason for my start and my struggle with it was that no matter how much money I paid, I couldn’t find an instrument I was happy with.”

The film makes clear that most traditional instrument players in Japan belong to a certain “scene,” aka, a rigidly defined hierarchy of student and teacher that perpetuates certain schools or styles. Neptune has never followed that path. As a fellow musician notes, “John belongs everywhere, and yet nowhere.”

“Where do you think you belong?” he was asked at FCCJ. “No matter what kind of music you make or the communication you have with an audience, whether I’m playing solo or particularly when I’m working with other musicians, there’s a connection,” he said. “We share this love of music.”

David explains the three stages of the filmmaking process. ©Koichi Mori

David has a global following for his comedy shorts on YouTube and Facebook, has won awards for a short horror film and has worked in a wide range of film industry positions, from interpreter to producer. But he had never made a documentary, and Words Can’t Go There marks his feature debut.

Asked how he knew when he’d completed the film, the director responded, “There were [essentially] three stages to making the film, which took 5 years. We shot about 500-600 hours of footage, enough for three different films, and there were probably three completely different films during the editing process.

“The first stage was me following my dad around with the camera, learning the process of documentary filmmaking. I followed him to schools in the Tohoku area, which was tough on me. It was hard to curb my own expectations, so the first stage was the reality shock of that. I felt destroyed. I was completely disappointed in myself.

©Koichi Mori

“The second stage was when I finally put footage together from that 3-week trip and started showing a sample to people in LA. I was fortunate enough to put this great team together and we went back to Japan and filmed with Bennett. Then I thought, 'Now I’ve got a film.' I was feeling really good. Little did I know that I was still 3 years away from finishing.

“Then I asked my dad to send me some of the old VHS tapes that we had in our house in Kamogawa. He sent me a box with 56 tapes, and that wasn’t even half of them. They were all moldy from sitting in a humid closet in the countryside of Japan. But we found a guy who could actually clean and digitize them, then it took weeks to watch them. That was a huge thing that shifted the direction of the film, since I realized that we could illustrate things like the foreigner as a bear in the circus idea.”

©Koichi Mori

What about that image of the lonely bear? “The lonely part comes with the daily practice and the composing and the working on flutes,” said John. “Those are solo activities. But when I perform the composition or sell the flute, then there’s the communication… the music brings us together.”

Despite his renown and dizzying performance schedule, Neptune does not have a fulltime manager and continues to do his own scheduling. “There was a period when I took any job I could get,” he explained. “The bottom line is, music is fantastic but music business is not so fantastic. If you’re doing a party for a big company, they’re not coming to listen to music. You’d prefer that they listened, but when they’re not, we do our own thing on stage and have a good time. But I ask for a lot more money than if someone asks me to play for a school and says, ‘We’d love for you to come and play for the kids, but we don’t have a big budget.’ That ’s why I never lasted very long with a manager. Their primary focus is to promote you and to make money. I decide how much I ask for each individual job. The music business isn’t interesting, but the music itself makes up for it.”

Kaizan plays near his home in Chiba.

2019 ©️ Ocean Mountain, LLC

And what of teaching, the mainstay for most professional musicians? “When I started becoming a professional, one of the things I did was teach,” John admitted. “When I got busy performing, I couldn’t always make time for teaching regularly. I decided not to teach when I moved to Kamogawa about 35, 40 years ago.” David interjected, “He doesn’t really like teaching.” John nodded, “Yeah. It’s a wonderful thing, and in Japanese society, the sensei is right up there. I do seminars and workshops at special events.”

John Kaizan Neptune’s example and his enthusiasm continues to inspire musicians of every age, both at home and abroad. If you don’t have to chance to see him on stage, then do not miss this beautiful film about being an artist, a parent and a legacy.

Father and son rock the take-da together. ©︎FCCJ

2019 ©️ Ocean Mountain, LLC

Posted by Karen Severns, Saturday, September 28, 2019

Selected Media Exposure

Read more

Published in: September

Tag: David Neptune, John Kaizan Neptune, documentary, shakuhachi

Comments