Like many nations with colonial pasts, Japan once deployed a policy of forced assimilation, economic and social discrimination, even family separation against its indigenous Ainu people — almost completely erasing their culture and identity. In the 19th-20th centuries, the government denied them the right to speak their language (it has been classified as critically endangered by UNESCO), as well as their right to hunt and gather.

Only with the 2019 passage of the Ainu Policy Promotion Act, the first recognizing them as an indigenous people, were the Ainu extended the right to “live with pride in their ethnicity” and to be afforded equal treatment.

Takeshi Fukunaga’s beautifully crafted second feature, Ainu Mosir, thus arrives at an auspicious juncture. Five years in the making and already the recipient of several major international festival awards, it portrays, in the guise of a gentle coming-of-age tale, the ongoing challenges facing the natives who call Hokkaido’s Akan Ainu Kotan home.

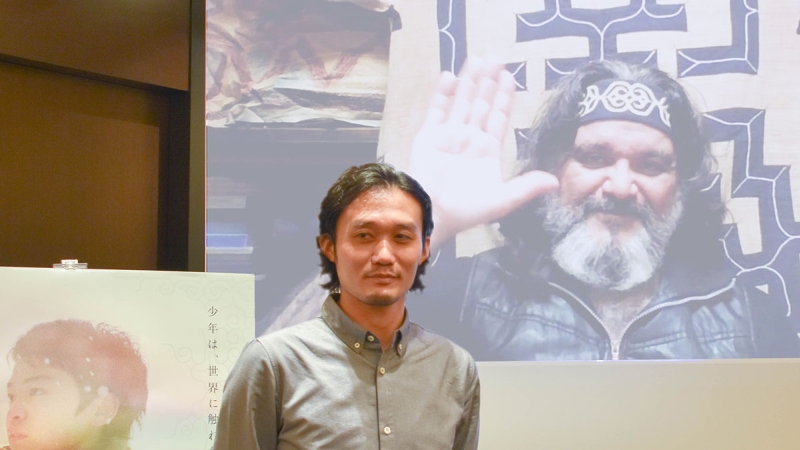

Fukunaga smiles at Debo, on a screen to his left. ©Koichi Mori

Fukunaga first appeared at FCCJ in 2017 with his debut feature Out of My Hand, which he had shot partially in Liberia and in New York City, the director’s adopted home for 16 years. With Ainu Mosir, the Hokkaido native once again demonstrates that he is uniquely positioned to tell stories about outsiders that are also universally human stories.

The film focuses on Kanto (Kanto Shimokura) a sensitive 14 year old who lives in Akan Kotan, a UNESCO World Heritage site. His mother runs one of Akan’s craft shops and takes part in the nightly performances of Ainu music and dance “traditions,” which are accompanied by flashing lights and videos.

Akan is “too tiny, it’s not normal and they make you do Ainu stuff,” complains Kanto, who would rather sing “Johnny B. Goode” in his middle-school rock band. But like the other students, he is deeply conflicted about his sense of identity.

©AINU MOSIR LLC/Booster Project

When a family friend named Debo (Debo Akibe) takes him under his wing, it’s clear Kanto has yet to come to terms with the loss of his father a year earlier. Debo teaches him the ways of their ancestors, shows him the path to the other side of the world where the dead live, and asks him to help raise a bear cub he’s keeping.

What Kanto doesn’t realize is that the bear is to be sacrificed in the ancient religious rite known as iomante, to thank the kamui gods for the gifts they have bestowed upon humans. But the controversial ritual has not been observed since 1975 in Akan (although the last one in Hokkaido was performed in 1990), and the villagers are at first opposed due to the impact it would have on tourism. “People won’t accept it!” protests one. “No one else needs to understand,” says Debo. “This is about us.”

©AINU MOSIR LLC/Booster Project

As Kanto grapples with his shifting sense of morality and takes his first tentative steps toward manhood, Ainu Mosir remains gently non-judgmental, fully immersing viewers in the quotidian sounds and sights of this colorful indigenous community, engrossing the viewer in this young man's journey toward understanding and acceptance.

Appearing after FCCJ’s screening, Fukunaga told the audience that his intention was always to work with a (primarily) non-professional cast of locals.

©Koichi Mori

“Being from Hokkaido myself, I realized after I’d left that I hadn't had a chance to learn about the indigenous Ainu people,” he explained. “Only after moving to the states did I recognize that I wanted to make a film about them. However, as a Japanese, or what the Ainu people call ‘Wajin,’ I knew I had to be very careful about depicting them, since I wanted to stay away from anything contrived or romanticized, as often occurs.

“I did write dialogue, but I didn’t want [the cast] to memorize it, I wanted them to express things in their own words, in a way that was close to their own stories. I tried to create an environment in which each of the cast members felt free to act in a natural way. I didn’t direct them as much as I would had they been professional actors.”

©FCCJ

Debo Akibe, who joined Fukunaga via Zoom from Akan, was one of the exceptions to the “non-professional” rule, having appeared in such films as Lee Sang-il’s 2013 hit Unforgiven, alongside Ken Watanabe and Koichi Sato. In fact, one imagines that Akibe is the exception to quite a few rules. His character in Ainu Mosir is both frightening and admirable, yet his doting tutelage of young Kota makes him an endearing father figure at the same time that he is a formidable defender of the Ainu tradition.

“How close are you to the amazing character you play?” he was asked. “There are similarities,” Akibe admitted,” but I don’t think I have as much perseverance and I’m more short-tempered. I wouldn’t have the patience to teach that young man so [wisely] and gently, as my character does in the film.”

That “young man,” Kanto Shimokura, also came in for his share of praise. Discussing the casting, Fukunaga explained, “We’d already decided that we were going to shoot in Akan, so our choices were quite limited. We needed to select someone who was in junior high school or below (Akan does not have a high school, so students must go elsewhere) or a much older man. The woman who plays Kanto’s mother in the film is his actual mother, and she was really cooperative, and introduced us to all the townspeople. Through discussions with her, I met Kanto early on. I knew he had a special presence, a special sensitivity about him.

©AINU MOSIR LLC/Booster Project

“When we rewrote the script and made [the character] younger, we immediately cast Kanto. It was an easy choice because we’d already built a relationship with him through preparations for the shoot. He’s actually very interested in acting, so I think it was a good decision.”

Asked about his experience working with Shimokura, Akibe recalled, “The first scene we did in front of the camera, I was really surprised at what he delivered. With every scene from them on, he completely understood what he had to do and he didn’t second-guess himself at all. I don't know how many conversations he had with the director, but his presence went beyond acting.

“I wanted to make sure that my own performance didn’t feel actorly. I wanted to show something that didn’t look like acting. I was able to do that because of Kanto’s wonderful performance — as well as Mr. Fukunaga’s wonderful directing.”

©AINU MOSIR LLC/Booster Project

The film’s credits note that no animals were harmed in its making, and in fact, it depicts iomante only through a scratchy VHS tape that Kanto has found in his father’s things. Fukunaga and Akibe were asked how they had morally positioned themselves concerning the townspeople’s struggle to decide whether to resurrect the ancient ritual.

Said Fukunaga, “Debo-san gave me a lot of advice about this. Among the Ainu, some are opposed to resurrecting the ritual, and of course, some are not. They all have their own reasons for it. I couldn’t think of any other motif that captures the spiritually and culture of the Ainu so completely as iomante, and that’s why I chose to depict it.

“This is not a documentary, so what you see in the town meeting is fictional. But those who spoke out against it are actually opposed to it in real life, and the same goes for those who support it in the film. I don’t think I’m in a position to have my own opinion on this, but I wanted to depict the [town’s divide].”

©AINU MOSIR LLC/Booster Project

Akibe was candid: “That scene, in which the townspeople are deliberating whether or not to go forward with iomante, had no dialogue written for it, so what you see is an impromptu enactment of what it would be like. As for my own sentiments, I was surprised to discover that so many people were against the revival of the ritual.

“To tell you the truth, 10 years ago I had a little cub that I called ‘Chibi,’ or ‘Little One’ [just as my character does in the film], and I was raising it to ultimately kill him. But everyone was against it and I couldn’t find one person to join me. My wife told me that if I killed and ate him, she would leave me. So I had no choice but to give up on the idea.

“When it comes to issues like tradition and culture, through the process of participating in this film, I came to discover just how personally people in Akan take iomante, and how much they value life. I realized that reviving tradition is sometimes not the completely the righteous thing to do."

©AINU MOSIR LLC/Booster Project

A Canadian cultural historian, noting that she shows Inuit and Mohawk films in her classes, said, “We have a similar colonization history, where filmmakers stole the stories of the native people, and now the native people are telling the stories themselves. I wonder if Mr. Akibe could talk about the decision to accept Mr. Fukunaga into the community and the relationship you had with him.”

Akibe broke into a wide smile on the Zoom screen. “The first time I met him,” he said, “my impression was, ‘Ohhhh, this is going to be complicated.’ After we had talked about the kind of film he wanted to make, and heard that he wanted to depict the iomante ritual, we knew it would be difficult. But he was very passionate about it, and he was able to convince me to believe in it, to want to help him. I felt that if a director was that serious about a film, then it would a success.”

He continued, “Throughout these 160 years, the Ainu and indigenous peoples around the world have been through dire straits as the colonists stripped them of their culture and their language. Of course it’s understandable that there are many indigenous people today who are still suspicious of the colonists and remain very resentful.

©FCCJ

“But across these past few decades, I’ve seen that kind of sentiment gradually wane, and everyone now seems to accept the notion of thriving together.* I did make one special request of the director. I wanted him to make sure that the revival of the tradition would not be depicted as any sort of revenge of the Ainu against the non-indigenous people.”

Indeed, one of the film’s many strengths is Takeshi Fukunaga’s restrained, non-judgmental depiction of cultural practices that are unfamiliar to most. Ainu Mosir should help to change that, as should the new National Ainu Museum and Park, which opened in July in Shiraoi, Hokkaido, with the mission of reviving and developing Ainu culture.

Viewers in the U.S. will also have a chance to see the film, after the just-announced acquisition by Ava DuVernay’s Array Releasing, which focuses on stories by and about minorities. They also distributed Fukunaga’s Out of My Hand, and will play this theatrically in select cities in November before debuting on Netflix.

©AINU MOSIR LLC/Booster Project

Posted by Karen Severns, Sunday, October 11, 2020

Selected Media Exposure

Read more

Published in: October

Tag: Takeshi Fukunaga, Ainu, indigenous, discrimination, Hokkaido

Comments