Speaking onscreen via the aptly named FaceTime, which leant him a physical presence that was as impressive as his eloquence, director Joshua Oppenheimer described his first meeting with Adi Rukun in 2003. Adi is the indelible hero of The Look of Silence, the exceedingly powerful companion piece to Oppenheimer’s Academy Award©-nominated The Act of Killing, the controversial 2013 juggernaut that swept over 50 major international awards and prompted a hand-wringing reconsideration of the very “rules” of documentary filmmaking.

“There was one victim of the [1960's Indonesian] genocide whose name was almost synonymous with the entire genocide,” Oppenheimer explained, “and that was Ramli. Unlike tens of thousands of others who had been taken away from political prisons, killed at rivers and left to drift out to sea, Ramli’s murder had witnesses… Talking about him became an act of resistance, in a place where people had been traumatized, but threatened into pretending that nothing had happened. Inevitably, I was introduced to Ramli’s family, and his mother wanted me to meet Adi right away. She said ‘he’s exactly like Ramli, his body language, his looks, his way of talking, they’re the same.’”

We first see Adi watching footage of his neighbors bragging about how they dragged Ramli to the Snake River, beat him, sliced him open, ripped off his penis and dumped him into the water to die. The boasts may sound just like those of the preening perpetrators in The Act of Killing, whom Oppenheimer had allowed to re-enact the massacres as if they were making a Hollywood horror movie. But with The Look of Silence, the emphasis shifts from the murderers to the Rukun family, standing in for the families of the million genocide victims.

This is the film that the director first set out to make 10 years ago, when he turned his lens on the taboo subject of the genocide, examining how the survivors and victims’ families continue to live side-by-side with the killers — who remain in control of the country to this day. But early in the 5-year filming process, at the urging of Adi and his family, Oppenheimer began to focus instead on the charismatic, sadistic Anwar Congo, who despite his crimes, remained a powerful, celebrated local leader. How, the family wanted to know, was he able to explain away his guilt, to demand that his grisly conquests were all in the name of ridding the country of communism?

Oppenheimer spent over 10 years bringing both films to the screen.

Returning to Indonesia in 2011 to complete a follow-up before the release of The Act of Killing made it impossible to safely go back, Oppenheimer discovered that Adi had decided to confront his brother’s killers himself; motivated not by revenge but by the desperate need for closure. The director wasn’t easily convinced. As he told the FCCJ audience: “I realized we would fail to get the apology Adi wanted… In one hour with Adi, these men [would] not be willing to go to that place of guilt and [wouldn’t] admit that what they’ve done is wrong. But I also realized that if I do my job well and capture the shock, the shame, the fear of guilt, the panic, the anger, the threats or whatever comes next, then we can show how torn the society is, how urgently truth, reconciliation and some form of justice are needed, and we can inspire younger Indonesians to fight for that. So maybe we can succeed in a bigger way with the film, even if we fail in the individual confrontations.”

And so The Look of Silence found its voice.

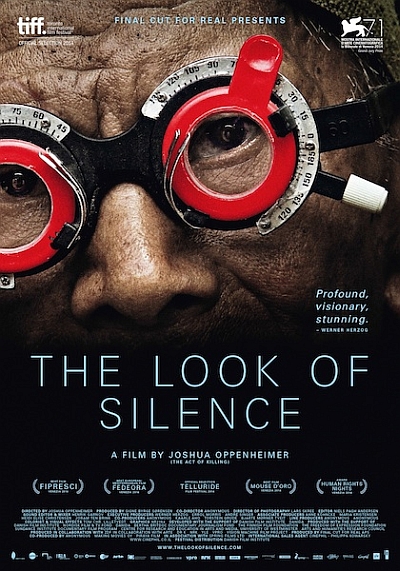

A gentle, serenely composed optometrist, Adi is pure steel in his mission to face the aging leaders of the village death squads, to surmount the impenetrable walls of silence masking their past atrocities. Under the guise of testing their eyesight — a perfect metaphor for the myopia that afflicts his nation — Adi begins his questioning, quietly listens to the perpetrators’ justifications, politely presses them for more answers, and asks them to accept responsibility for their actions.

Amir Siahaan, who oversaw the 3-month-long slaughter of 500 “communists” at Snake River in Medan, tells his interlocutor: “America taught us to hate communists, so we should be rewarded with a trip to America [instead of accusations].” M.Y. Basrun, speaker of the national legislature for the past 40 years, insists: “The mass killings were the spontaneous action of the people. They hated communists.” When Adi persists in his probing, the former head of the Komando Aksi death squads resorts to threats: “Do you want the killings to happen again? Then stop.”

Adi Rukun confronts one of the perpetrators in a scene from The Look of Silence.

© Final Cut for Real Aps, Anonymous, Piraya Film AS, and Making Movies Oy 2014

Adi does not flinch, even when one man tells him that all the killers drank the blood of their victims because otherwise they would go insane. “Human blood is salty and sweet,” he explains. In one of the film’s final — and most moving — scenes, the man’s daughter apologizes, visibly shaken by his confession. After a moment, Adi embraces her. But it is the only truly conciliatory note in the film. To be sure, Adi’s bravery stemmed partially from the security measures Oppenheimer’s crew took (“we had two getaway cars, and help from the British and American embassies if we needed to get out of the country quickly”). Adi also accepted that he and his family would necessarily have to move away from Medan once filming had finished. They are now resettled in a much safer community, surrounded by like-minded souls, and Oppenheimer reports that “The children are in much better schools, and the family is relieved to be living a life away from being threatened day to day, which is how they felt for the past 50 years.”

Like The Act of Killing, which brought Oppenheimer in person to FCCJ in early 2014, this new film is absolutely essential viewing. More conventional, and thus more confrontational than the previous work, there is more of what one critic calls “the familiar embattled- interviewee choreography: the demands to stop filming, the shrill addresses to the director ‘Josh’ behind the camera, and the removal of the radio microphone.” Yet it is poignant, compassionate and deeply unsettling.

Joshua Oppenheimer

With The Act of Killing and now the equally unshakeable The Look of Silence, Joshua Oppenheimer has shattered the deafening, 50-year silence in Indonesia. The film has won a raft of international awards since earning the Grand Jury Prize at the Venice Film Festival upon its world premiere. But its greater achievement is that it played across Indonesia on nearly 500 public screens, allowing thousands of Indonesians to share what they could not with the first film, which was never screened. “The first film made it impossible for people to continue not talking about the regime of corruption, fear and thuggery that the perpetrators had built,” Oppenheimer notes. “The second film makes it impossible to continue to ignore the abyss [that] divides people. And that opens the way for activism in the sense that, once people are talking about a problem, they’ll propose solutions for it. You can’t solve a problem that you can’t even talk about.”

Oppenheimer also stressed the importance of viewing the films not as doors to some other culture on the other side of the world, but as mirrors for our own. In pointed comments that we would display in 20-point boldface if it were possible, he cautioned: “If there are two key messages in these films, the first is that every perpetrator in history is a human being like us and we must contemplate ways to understand that we’re all closer to perpetrators than we like to think. The second message, which is particularly relevant to Japan at this moment, considering the proposed changes to the constitution, is that we can never run away from our past. It’s always with us. We are our pasts. It will damage our future if we cannot find the courage to… accept all the things that make us what we are, acknowledge the violence and terror, not make excuses for it, and not generate vicious patriotic rhetoric celebrating or justifying it. We need to take responsibility for what we are, so we can proceed wisely into the future.”

— Photos by Koichi Mori and FCCJ.

© Final Cut for Real Aps, Anonymous, Piraya Film AS, and Making Movies Oy 2014

Posted by Karen Severns, Saturday, July 04, 2015

Read more

Published in: July

Tag: Joshua Oppenheimer, documentary, Act of Killing, awardwinning, genocide, Indonesia, Oscar, international coproduction

Comments