Issue:

April 2023 | Letter from Hokkaido

The G7 environment ministers’ summit in Hokkaido will take place amid a legal row over indigenous fishing rights

Foreign VIPs coming to Sapporo on April 15-16 for the G7 Climate, Energy, and Environment Ministers’ meeting have a packed schedule: cozy dinners with Hokkaido leaders one night and official receptions with central government officials the next. Bilateral meetings with fellow G7 partners on the side to discuss energy-related trade deals, and – oh, that’s right – meetings with everyone in the room to discuss the current state of climate change, the energy supply, and the environment.

For delegates wishing to stick around after the meeting concludes, trips to a local park and mountain are in the works. Before everyone heads back to Tokyo on April 17, there is also a planned stop at the Upopoy National Ainu Museum, where visitors will get the Japanese government-approved version of Ainu history.

The museum tells the story of Japan’s indigenous people via a series of panels – a basic overview that has drawn fire from Ainu scholars and activists who describe the museum’s narrative as a whitewashing of history that reflect the authorities’ desire to propagate the official view than to tell unpleasant truths. The way aspects of Ainu history are presented could generate diplomatically awkward questions from delegates from countries where indigenous rights are front and center in any political debate.

For example, one panel reads (in English): “The Ainu would catch salmon in weirs and hunt deer with poisoned arrows, but the Hokkaido Development Commission banned those traditional customs. Although this dealt a severe blow to their livelihood, they rose to the challenges of the times, such as learning how to use guns for hunting.”

The problem – besides the fact the panel makes no mention of why these customs were banned or how Ainu people reacted at the time – is that visitors are invited to conclude that the Ainu learned how to use guns and moved on. Problem solved.

Well, not quite.

What G7 delegates are unlikely to hear is that not all Ainu groups feel the same way about the loss of their traditional hunting and fishing rights. Nor are they likely to hear much about the fight by one Ainu group in particular.

The Raporo Ainu Nation in Hokkaido’s Urahoro district, located between Obihiro and Kushiro, has been fighting a court battle since 2020 to win back salmon fishing rights. In their claim, they note that, in the late 19th century, the Meiji government completely banned salmon and trout fishing in Hokkaido, including individuals who fished for those species to eat at home.

“Today … salmon fishing in rivers is prohibited by both the national government and the prefectural government of Hokkaido as a general rule applying not only to Ainu, but also to Wajin. The only exception with respect to the Ainu is that the Hokkaido prefectural government allows a designated number of salmon to be caught for the purpose of cultural transmission,” the English translation of the claim says.

“While the legal basis for the prohibition against salmon fishing for various Ainu groups since the Meiji period was never clarified in the first place, it is nevertheless considered illegal.”

If G7 visitors to Sapporo don’t hear about Ainu fishing rights and their connection to the environment, no one should be surprised if the Suttsu area of Hokkaido also fails to get mentioned, especially if discussion turns to Japan’s “green transformation” under Prime Minister Fumio Kishida and its emphasis on a bigger role for nuclear power.

Suttsu, a five-hour bus ride from the G7 venue and just over two hours from the Niseko ski resort, could eventually become the long-term – as in up to 100,000 years – burial site for Japan’s spent nuclear fuel, a prospect that horrifies many Hokkaido residents.

Of course, all of the G7 meetings at the ministerial level are dress rehearsals for the main leaders’ summit in Hiroshima in May, when nuclear weapons, not nuclear power, will be on everyone’s mind. It will not be the first time that local issues and their relationship to climate change and the environment, regardless of whether other G7 nations share similar experiences, get short shrift among a G7 host keen to set its own agenda and focus on the bigger picture.

But for those who arrive in Sapporo with a deeper interest in the environment, climate change and local issues, Ainu fishing rights and worries over Suttsu’s future would be far more instructive than the currently planned excursions. They would at least offer insights into official Japanese thinking on important environment and climate change policies.

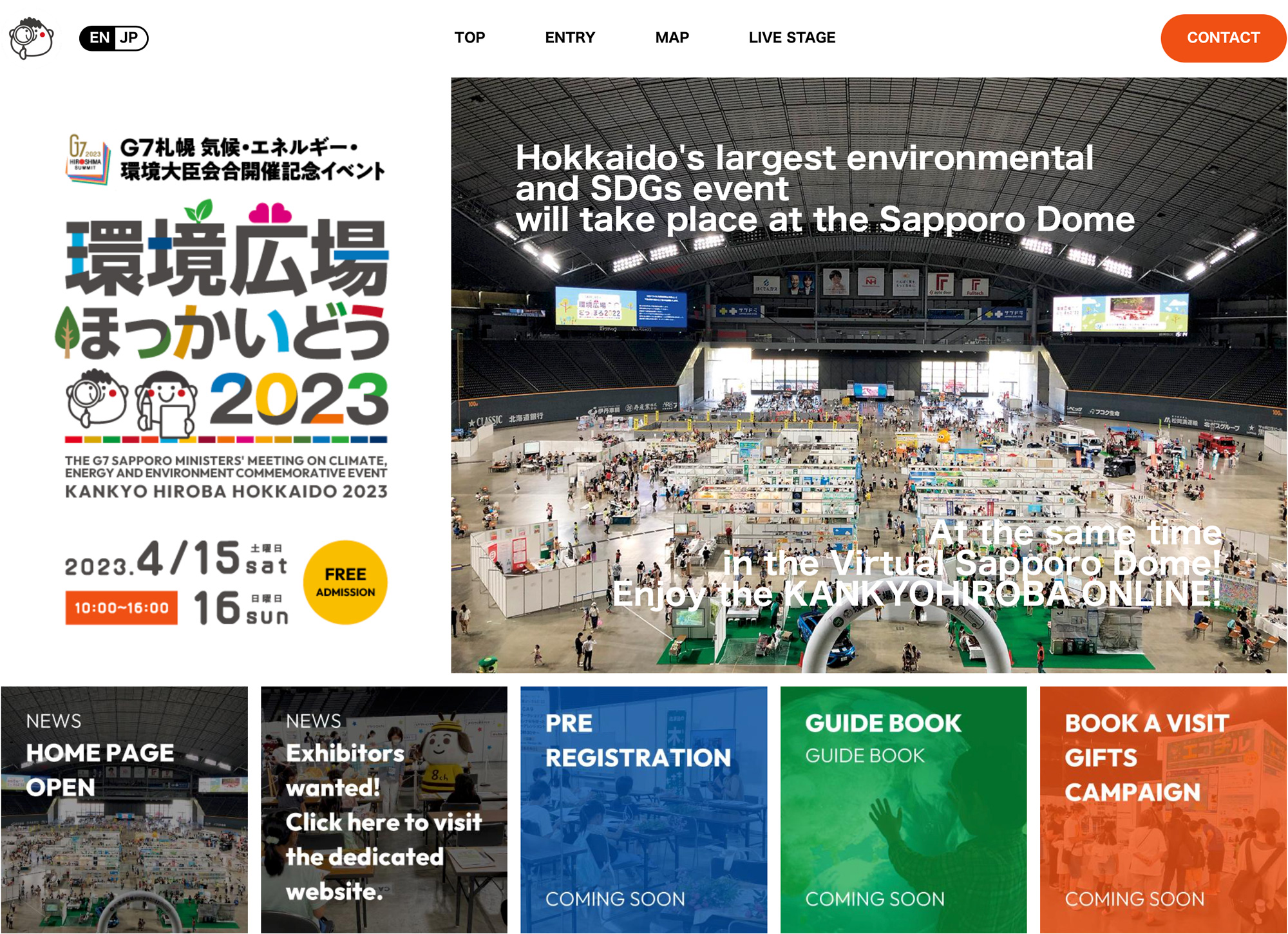

One group of Hokkaido residents has decided to let everyone know how they feel about environmental, energy, and climate change issues. On the same weekend as the G7 meeting, the G7 Earth Day Open Forum Hokkaido takes place at a downtown Sapporo high school just a 10-minute walk from the venue and press center.

Dozens of Hokkaido-based environmental experts, NGOs, activists, and others will conduct symposiums and workshops about the impact of climate change, biodiversity loss, renewable energy, and environmental problems confronting not only Hokkaido and Japan, but the entire world. They are especially keen to meet visiting FCCJ members who want to cover something other than the G7 ministers’ lunch menu, grip-and-grin photo sessions, and bland, predictable press conferences.

Those of you who are interested in learning more about the Open Forum are invited to contact Miki Arisaka at arisaka@rce-hc.org in English or Japanese for more information. I hope to see many of you in Sapporo later this month.

Eric Johnston is the Senior National Correspondent for the Japan Times. Views expressed within are his own and do not necessarily reflect those of the Japan Times.