Issue:

June 2025

Marilyn's transformational journey to Tokyo

Following is an edited extract from a book about Marilyn Monroe that Mary Corbett was working on before her untimely death earlier this year.

Longtime FCCJ member Mar Corbett was in the process of writing a book about one of her favorite subjects - the transformational 1956 honeymoon to Japan of Marilyn Monroe and Joe DiMaggio – when she died of a heart attack at the age of 68.

I had been helping Mary edit the book, providing feedback in the months leading up to her death. After her passing, her family asked me to continue the project. With help from Tom Tyrell of the Yokohama Country and Athletic Club, they handed me stacks of hard copy and several laptops containing material related to Mary’s work.

After wading through it all I came to the conclusion there wasn’t enough there to complete the book, which deals with the significance of Marilyn’s time in Japan, and how it convinced her to take control of her career and assert her independence from Hollywood studios.

However, several segments are worth publishing, including the one below. The material was culled from contemporary media accounts in English and Japanese, and interviews with people who interacted with Marilyn and Joe in Japan.

I hope you enjoy it as much as I did, and I hope to provide more excerpts in the coming months.

Robert Whiting is a best-selling author and journalist who has written several successful books on sport and contemporary Japanese culture, including You Gotta Have Wa (1989), The Meaning of Ichiro (2004), Tokyo Junkie (2021) and Gamblers, Fraudsters, Dreamers & Spies: The Outsiders Who Shaped Modern Japan (2024).

Over 60 years after her death, the fascination Marilyn Monroe continues to elicit around the world through a cascade of books, films, media talk shows and record breaking auctions, remains a cultural phenomenon in and of itself. Yet missing from the countless iterations of “in-depth”, “intimate” and “never before told” tales feeding into demand for paths to understanding the “true” Marilyn, is any meaningful insight into her transformational 1954 journey to Japan with Joe DiMaggio and the impact it had on a nation that, despite still being buried in the ruins of World War II, fell deeply in love with her.

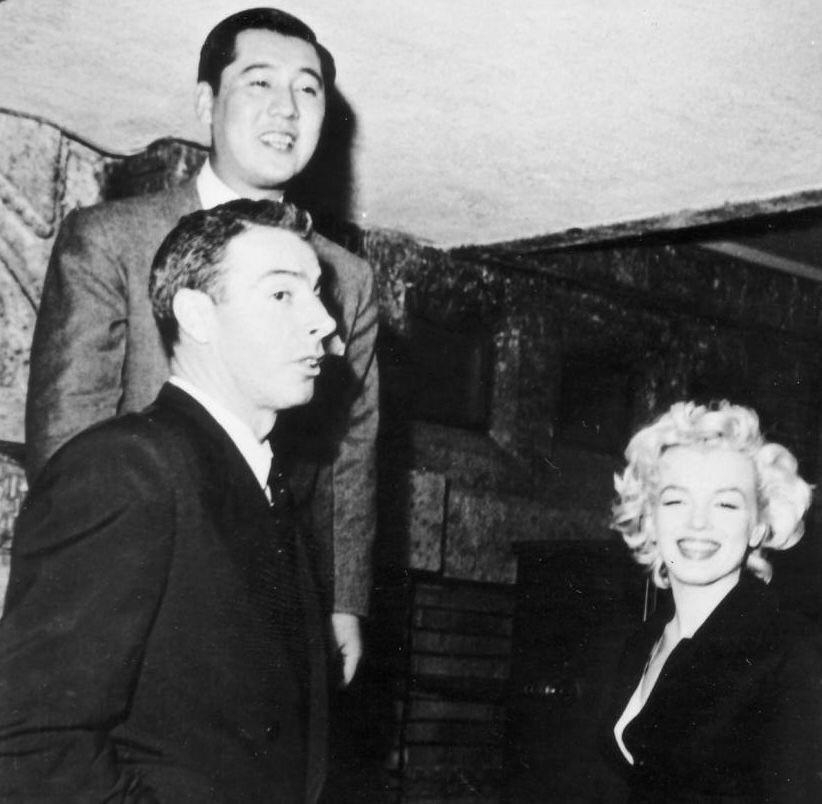

The trip was piggybacked on a minutely orchestrated three-week DiMaggio barnstorming tour of cities across Japan in support of local professional baseball teams were still recovering from the effects of the war. After nearly two years of a romance that was covered relentlessly by the media, Joe and Marilyn finally tied the knot in a lowkey civil ceremony on January 7, 1954, and headed across the Pacific soon after. The primary movers of the tour were Joe’s mentor and manager from his days at the San Francisco Seals, Lefty O’Doul, himself a former Major League standout and frequent visitor to East Asia, along with Japan-U.S. sports events coordinator Cappy Harada, who had woven together a 24-day whistle stop itinerary for the newlyweds that is etched in the collective Japanese memory to this day.

A baseball-themed tour of any sort would not have been Marilyn’s first choice for a holiday, much less a honeymoon. She had little interest in or knowledge of the sport, but she was eager to show the world, and her husband, that the new priority in her life was to be a good wife to the world famous sporting legend. Tour leader O’Doul was already a household name in baseball-mad Japan. He had first visited the country 20 years earlier as a member of the U.S. American League All-Stars team remembered as the “Immortals”. The team included Lou Gehrig, Charlie Gehringer, Lefty Gomez, Connie Mack, Jimmie Foxx and Babe Ruth, the most famous and beloved athlete of his day.

The tour had raised baseball’s already considerable popularity in Japan to unprecedented heights, after which O’Doul had become a prominent adviser to Japan, and later the first non-Japanese inducted into the Japanese Baseball Hall of Fame. The war had created a predictable dip in the professional league’s popularity O’Doul had helped to create. However, in 1950, when Joe first travelled to Japan as part of an All-Stars team, American-style baseball was welcomed by enthusiastic fans lining the streets for miles on end, waving American flags, and proclaiming him the Living God of Baseball, the heir to Babe Ruth’s sacred mantle.

Marilyn and Joe’s honeymoon was filledwith visits to professional teams’ batting practices, autograph sessions, interviews and dinners with hosts and sponsors. Their itinerary left little time for romantic side trips or intimate candlelit dinners. It must also be remembered that in those days, most Japanese towns large enough to host a professional baseball team had been the target of intense bombing towards the end of the war. Nine years after Japan’s surrender, basic infrastructure had yet to be restored in many regions, and urban centers that Joe and Marilyn visited still stood like open wounds in various stages of rubble, shanty towns and stalled reconstruction projects. The vista was still a universe away from the world’s favorite travel destination Japan was to become when the country reinvented itself, with considerable support from the United States, in time to host the 1964 Summer Olympics.

That transformation would have been unimaginable to any observer in 1954, as it still was as late as 1959, when Tokyo’s official selection as the host of the 1964 Games was announced, leaving American journalists on the ground amazed that a ramshackle town covered in dust – and where less than 20% of the populace had access to flush toilets, not to mention a dearth of sporting facilities – should have been selected over Detroit, then at the height of its power, and Vienna, like its American competitor eager and ready to welcome the world.

For Marilyn, fresh into her suspension issued by 20th Century Fox for refusing to report to the set of a film tentatively titled The Girl In Pink Tights the previous month, flying off for three weeks on an Asian odyssey with Joe was a defiant challenge to the powerful figures who had confined her to a virtual indentured career in a revolving door stable. Fox frequently reminded Marilyn that it had access to a pool of interchangeable blonds capable of filling her shoes. After delivering back-to-back hits Niagara Falls, Gentlemen Prefer Blonds and How To Marry A Millionaire in 1953, she could be forgiven for feeling more deserving of nominal script approval privileges and pay befitting her meteoric rise at the box office.

Jane Russell expressed sympathy for Marilyn in interviews after their starring roles in Gentlemen Prefer Blonds, which had Russell taking home nearly 10 times Marilyn’s pay. However, Marilyn was now armed with a husband who was arguably the most respected and beloved icon in America. This gave her a kind of safe haven against the studio’s tyranny, Joe’s surly contempt for just about everything Hollywood stood for notwithstanding. The matter of how someone as ferociously disdainful of the media as Joe DiMaggio could contemplate building a traditional family life with the now-famous and unapologetic nude pinup star with an insatiable thirst for publicity aside, it had never been Joe’s intention to support Marilyn’s career as an actress. He was simply outraged by the studio’s culture of exploitation that had effectively held his wife captive.

The Japan trip also paved the way for Marilyn’s historic four-day concert detour midway through the honeymoon to entertain U.S. soldiers in Korea. Not only was the tour a dream come true for Marilyn, who had credited the fan mail soldiers sent from the trenches for triggering her career breakthrough in 1951 in the wake of her hit Niagara. It also cast her time away from Hollywood on the honeymoon in bright patriotic colors, as it was reported widely across the United States, serving to enhance Marilyn’s profile as America’s sweetheart in spite of the studio suspension and the sudden resurfacing, just weeks before her wedding, of a photo from her hungry modelling days as Playboy magazine’s epoch-making nude centerfold in their inaugural issue.

Marilyn’s hosts in Japan could hardly grasp the magnitude of their good fortune. For the Yomiuri group, publisher of Japan’s highest circulation daily and owner of the Tokyo Yomiuri Giants, Japan’s most popular baseball team, Marilyn’s addition to the tour was a windfall that was to boost their brand sky high and dominated the headlines long after the honeymooners had departed. The actress, already known in Asia for her sultry walk in a famous scene from Niagara, forever remembered in Japan as the “Monroe walk”, would be the crown jewel of Joe’s triumphant return to a land where baseball was the national sport, and a publicist’s dream come true.

Largely hidden behind the thunderous voltage of the couple’s combined celebrity, and the frenetic buildup to their arrival in Japan, was the depth of their tour's profound geopolitical significance: 1954 was a pivotal year in the violent shift of dynamics across the region. With the Korean war having ended in 1953 in a complex stalemate, the lingering threat of communist expansion across Asia forced an about-turn in America's policy, shifting away from its immediate postwar aim of securing a peaceful democracy in Japan forever blocking any chance of a military resurgence. The new urgency was to quickly rebuild Japan’s industrial base and defense capabilities to create a much-needed viable ally in the region. The Japanese public was not as quick as had been hoped to embrace such fast-moving policy revisions, which included the proliferation of U.S. military bases across the islands. The United States had long regarded baseball as a cornerstone of the U.S.-Japan alliance and a bellwether of Japanese public opinion. The hopes of U.S. representatives on the ground were riding high on DiMaggio’s star power to bring back the American flag-waving enthusiasm that had greeted Babe Ruth before the war, and DiMaggio himself in 1950. Marilyn had little briefing on any of this, but there was no question that the Marilyn effect was expected to add a nice boost to the diplomatic endeavor. It was also a prime opportunity for the recently retired Joe to impress upon his bride the tremendous stature he continued to enjoy even beyond American shores.

Banner headlines heralded a national countdown to the baseball legend and his dazzling bride’s imminent landing. At the same time, neither the news of Marilyn’s most recent megahit How To Marry A Millionaire, nor the sensational Playboy launch just weeks before, had yet reached the shores of Japan. Joe’s handlers on both sides of the Pacific Ocean naturally expected Marilyn would be the perfect eye candy on the arms of the great DiMaggio to generate publicity for his much anticipated return. They also surmised that the trip would serve as a nice break for Marilyn away from the pandemonium that followed the newlyweds everywhere in the United States, since, they believed, she was not quite yet as well known in Japan. Joe himself mentioned to Cappy Harada the need to give Marilyn a break from the intense fan and media scrutiny in the U.S. as the primary reason for wanting to travel overseas when they first explored the idea of a trip to Japan.

How wrong they were. Within minutes of their Pan American Airlines super luxury Stratocruiser B-377 aircraft touching down in Tokyo, fans and press broke through the fences and surrounded the honeymooners’ aircraft, with frenzied chants of “Monroe!”, “Monroe!” ringing across the runway, promoting Japanese police to call for reinforcements from a nearby U.S. military base. DiMaggio visibly fumed at his sudden conspicuously supporting role. However badly Joe’s minders may have misread the demographics, the landing itself marked a historically joyous moment for Japan. The pandemonium put Haneda Airport on the world’s radar, as the nation took tentative steps towards its reemergence on the international stage after its wartime defeat. Nothing like it would be seen in the usually well-mannered and orderly town until the arrival of The Beatles in 1966.

For the newlyweds, however, it was to prove the beginning of an unforgiving Litmus test that publicly exposed the extreme vulnerabilities of a relationship that early witnesses in Japan were already suspecting would not last. Marilyn soon became too much of an irritating distraction at events organized for Joe, so her appearances at baseball events were reduced. Joe was unhappy about Marilyn flying off to Korea to entertain U.S. troops, but held his wrath in check, some observers noted, for fear of being seen as unpatriotic. By the time Marilyn returned from her triumphant four-day concert tour to rejoin Joe and his friends for a weekend at the exquisite Kawana Hotel overlooking the sweep of breathtaking Sagami Bay, the strain was palpable.

The tour gave Japanese fans a glimpse of the American dream they saw personified in Joe and Marilyn, in an age when romantic love was rarely expressed in public. Although Japan was still years away from embarking on its economic miracle, every stop on the tour inspired virtual shrines dedicated to the memory of the couple’s “heavenly visitations”. Every meal the press reported Joe and Marilyn enjoying, or a simple beret Marilyn was wearing, would become the subject of quests for fans to experience the same, though the price tags were far beyond the reach of most Japanese, whose average annual income in 1954 hovered at around $500. Just as America endeavors to this day to find the remotest Marilyn link to boost interest and sales of a book or product, Japanese towns are eager to let visitors know that “Marilyn was here,”’ albeit in some cases for just a few minutes, 70 years ago.

The three weeks in Asia would spark a momentous shift in Marilyn’s life, not only for the unprecedented frenzy her honeymoon trip generated, but also for the career-changing stage it triggered, far from the influence of her studio and the Hollywood media. Her new trajectory started to unfold even before she had touched down in Japan. Joe and his entourage saw Marilyn board a flight in California, a sweet starlet on her proud American icon’s arm, and witnessed a full-blown goddess disembark at Haneda International Airport on February 1, 1954. It may have been the unexpectedly riotous welcome she had been accorded on their stopover in Hawaii, or the dream invitation she received to perform in Korea from U.S. military officers they met on the plane en route to Tokyo. Marilyn appeared to step off the luxury flight across the Pacific and cast off the shackles that had bound her throughout the long years under contract to 20th Century Fox and step into a new off-screen role.

By the end of a year that had begun with her suspension from Fox, Marilyn had made global headlines by marrying an American icon, swept Japan off its feet, and blissfully serenaded 100,000 troops in Korea - experiences she called the happiest moments of her life. She moved into the next chapter of her life inspired by a bold new strategy, in spite of still being held to what she considered the be “demeaning” Fox assignments, such as a small part in There’s No Business Like Show Business that she was committed to honor, along with her struggling marriage. Soon to follow was the iconic moment when her white dress billowed over her head in The Seven Year Itch – a turning point from which she never looked back. The “Marilyn Typhoon”, as the Japanese press gleefully hailed her historic landing in Japan, appeared at that moment to be an unstoppable force of nature.

In a dizzying succession of events packed into the crowded few weeks that followed her shoot in New York, Marilyn announced the end of her nine-month marriage to Joe and was feted by the cream of Hollywood aristocracy, who had gathered to toast the completion of The Seven Year Itch and welcome her into their ranks at Romanoff’s in Los Angeles, the legendary restaurant to the stars. Her childhood idol Clark Gable was there, as were Doris Day, Humphrey Bogart, and his wife Lauren Bacall, with whom Marilyn had co-starred in How To Marry A Millionaire, Gary Cooper, Jimmy Stewart, and William Holden, alongside the powerful Hollywood moguls Jack Warner and Samuel Goldwyn. Even her nemesis, 20th Century Fox president Darryl Zanuck, who just months before had deemed her a replaceable blonde bimbo, showed up to proudly laud Marilyn’s dazzling climb to the pinnacle of Hollywood.

What should have been a day to savor the respect of peers and idols she had craved for so long, was already dwarfed by ambitious preparations for the next grand chapter she had started to craft months before, even during her honeymoon. Unbeknown to the luminaries who gathered that day, or to her studio, or the husband she had just left, she was packing to move away from Los Angeles for a new life in New York, leaving incognito on a midnight flight with her new business partner, photographer Milton Greene, to announce the launch of Marilyn Monroe Productions, with Marilyn as its president.

For Japan, 1954 was nothing less than the unforgettable Year of Marilyn, when a goddess stepping out of the silver screen bestowed on the people a glimpse of the American dream just as the nation, too, was opening to a new world. It was also a year when the impoverished country's economic recovery was finally showing signs of growth. In an otherworldly coincidence, Marilyn’s greatest rival for the headlines in Japan’s entertainment annals of 1954 would be none other than the birth of its biggest international screen export of all time, Godzilla, himself an enduring icon of endless fascination 70 years on.

Three weeks in Japan radically realigned the stars guiding Marilyn’s career, while assuring her a place in the collective memory of an entire nation. It remains a uniquely Japanese phenomenon to this day. Kim Kardashian is not a familiar name to most Japanese, but attending the Met Gala in Marilyn’s gold dress from the legendary 1962 performance at President John F. Kennedy's birthday event alone earned Kardashian considerable press coverage in Japan. Marilyn Monroe remains a beloved and endlessly marketable icon in Japan, as she is, of course, around the world. The place she holds in the hearts of the Japanese, however, continues to enjoy a magical aura even today, rooted in the lasting mythology born that historic moment when the Goddess appeared at Tokyo Bay.