Issue:

March 2024 | Japan Media Review

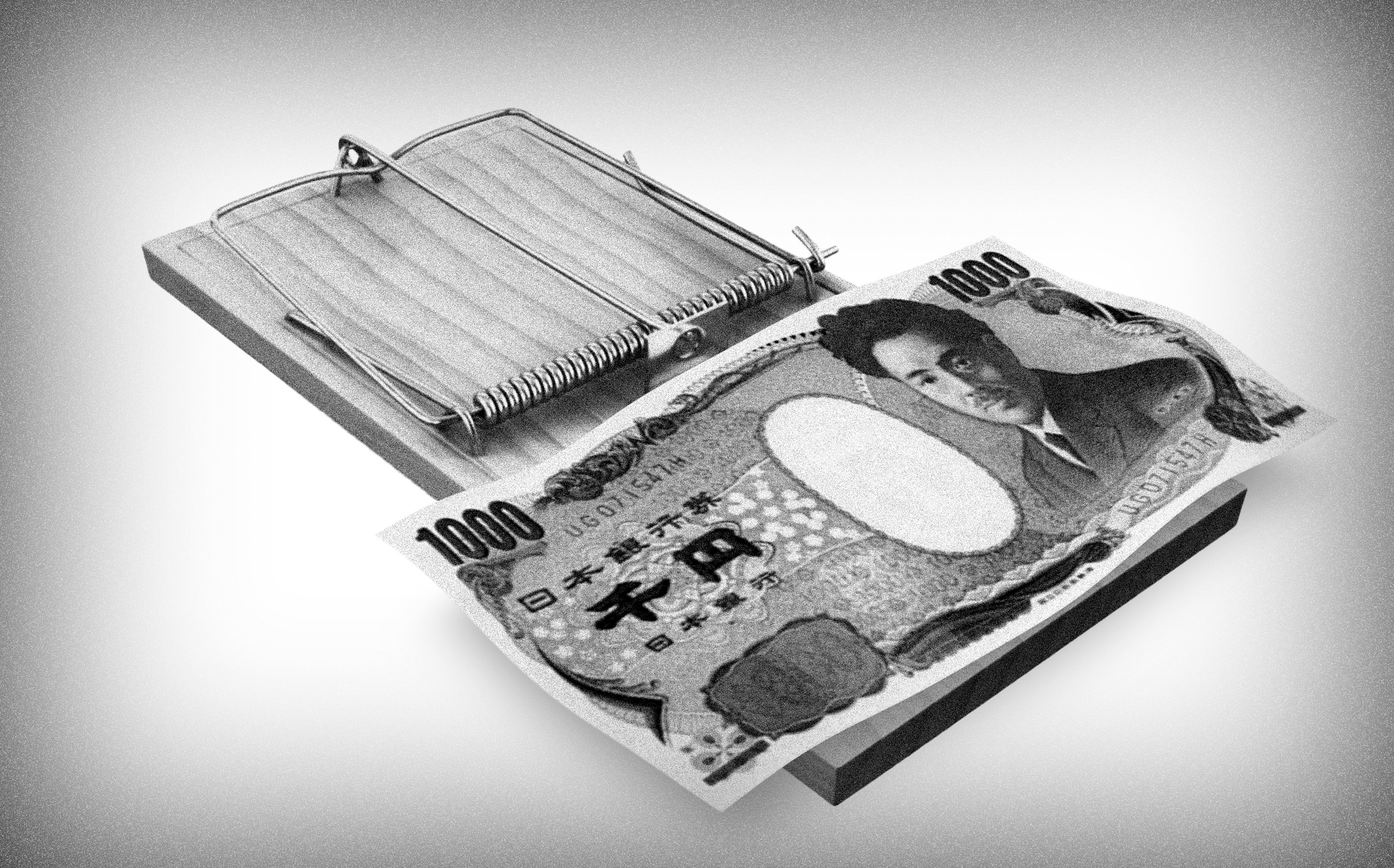

‘Poverty businesses’ are exploiting Japan’s most vulnerable for profit

Last autumn the Gunma Shiho-Shoshi Lawyers Association, a group of legal scriveners working in Gunma Prefecture, accused Kiryu city hall of short-changing an approved welfare recipient of his full benefits. The man, who was in his 50s, had been approved for public assistance in July and began receiving payments the following month. But instead of giving him the full ¥70,000 he was promised, the office required him to make daily visits to its counter, where he received ¥1,000. A representative later said the reason for this unusual procedure was the condition that the recipient visit an employment office every day to look for work and then bring them proof of the visit. The representative added that this scheme is used when the welfare official who approves benefits is afraid the recipient will spend the entire monthly payment right away.

The scrivener group, which the recipient consulted on his own, said that the daily payment system violated the constitution and the public assistance act, since the monthly sum of the daily payments fell well short of the ¥70,000 to which the man was entitled. The Kiryu welfare office admitted it had been wrong and paid the man all the money it owed him retroactively.

Although most Japanese media covered the story, the Tokyo Shimbun went deeper, running almost daily stories about the Kiryu welfare office between November 2023 and early January this year. This scrutiny uncovered another welfare-related story involving a foreign woman in her 60s whose Japanese husband died in January 2023.

In May, the woman, who had suffered abuse by her late husband's family, and her disabled adult son moved into their own apartment in Kiryu but only took some of their belongings, leaving the rest at the home of her in-laws. When she applied for assistance at the city office she was rebuffed because, according to the official who handled her case, she could not receive benefits until all her belongings had been moved to her new address, which would be used on the application. But as one lawyer pointed out to the Tokyo Shimbun, "People who evacuate [a residence] due to domestic violence usually leave their possessions at that residence."

The matter was not cleared up until October and the retroactive payments not made until mid-November. The city explained the delay by saying that it had trouble determining how much in national pension benefits the woman was supposed to be receiving. City officials said that these problems were merely oversights and denied that they were carrying out something called mizugiwa sakusen—literally, "water's edge strategy"—wherein bureaucratic functionaries prevent someone from even applying for a service. It's a term often used about public assistance, as those at the counter (the "water's edge") are instructed to pre-empt any possible abuse of the system. The practice has become normalized in many local governments, which have been told by the welfare ministry to keep payments to a minimum.

This bureaucratic mindset engenders an adversarial relationship between officials and welfare recipients. Case workers tend to be particularly over-burdened and often turn to third parties for help in carrying out their tasks. This situation has given rise to an enterprise known as the "poverty business" (hinkon bijinesu) – a term used to describe companies or organizations that help people on public assistance navigate their lives in exchange for the benefits they receive.

The most common form of poverty business involves housing. For years, some organizations have managed collective residential facilities for welfare recipients. To receive benefits in Japan, one must have a fixed address, so these organizations guarantee a residence and then accompany the person to the local welfare office to apply for benefits or instruct them on how to apply themselves. The organization then retains some or all of the benefits allocated every month for rent. The residences tend to be dormitories, with multiple people sharing a room. When welfare offices receive a query for benefits from someone who does not have a permanent address, some will refer the potential applicant to these organizations.

Since the end of the Covid-19 pandemic and the government's temporary policy of placing unhoused people in commercial accommodations, another kind of poverty business has emerged called anaumeya, or "the business of filling holes". The practice was reported in greatest depth by NHK last May on its web page Shutoken Navi. It first attracted attention as a side effect of the real estate boom that followed the pandemic. People who had invested in rental properties suddenly saw their tenants moving out, and when NHK investigated it found that in many cases the tenants were welfare recipients.

NHK focused on one investor, a salaried employee in his 40s who bought an old apartment building in Saitama Prefecture for ¥31 million in May 2022 by taking out a loan for the entire amount. The man wanted to save money for his children's education and thought real estate was the best bet. It was the first time he had ever invested in anything. At the time he purchased the building, all eight units were occupied, thus providing him with ¥330,000 a month in rental income. After subtracting the monthly loan payment, he was left with ¥110,000, which he felt was a fair return, even when he figured in property taxes and maintenance costs. The loan was for 18 years, and he assumed the income would be pure profit once he had paid it off.

However, these calculations were based on the belief that the building would have 100% occupancy. He also assumed that he would always be able to charge the same rent, which was high compared to market rates in the area. That's because some of the units were occupied by welfare recipients who were getting the maximum amount allowed for rental properties: ¥42,000. The other tenants who were not welfare recipients paid on average ¥35,000 a month. Local governments provide rental assistance and general assistance separately. Rental assistance is determined by the location of the residence and the number of persons in the household. In the city where the apartment was located, the maximum rental assistance for a one-person household was ¥42,000 a month, while the market rate for the kind of apartments in that building was ¥28,000 a month. The investor knew this. In fact, it was the main reason he thought the building was worth buying, because the tenants on public assistance were guaranteed to receive the rental allowance. He didn't have to worry about delinquencies.

But within a year of buying the building, five of the eight units became vacant, and when the owner tried to find new tenants at the same rate, he couldn't, and had to reduce the rent to ¥29,000. Even then, he only found one new tenant. Consequently, his monthly income fell by half, which was not enough to cover the monthly loan payment, so he had to dip into his savings.

NHK found other cases that fit the same pattern. In these cases, when an investor bought a building, it was 100% occupied, mostly by welfare recipients who would move out without giving prior notice shortly after the purchase was made. The buildings had been bought from real estate companies. When NHK tracked down some of the tenants it discovered that they had been recruited by organizations that work with realtors to fill up rooms in these apartments to make them attractive investments. Once the sale was complete, the organization relocated the tenants to another apartment building that the realtor was trying to sell. The tenants had originally answered ads placed by the organization, which said they would provide people who are normally shut out of the rental market with housing and help them apply for welfare. As already mentioned, many of these organizations also have relationships with local government welfare offices, which refer potential applicants to them to secure addresses.

A real estate expert told NHK that the scheme is probably illegal, but it would be difficult to prove that a real estate company is gaming the system since the tenants are moving at the behest of the organization rather than that of the realtor. In any case, buyers are always warned that all investments involve risk of some kind. When NHK called several realtors to confirm this practice, they didn't necessarily deny it but said that everything was above board, adding that if there were any problems it was because the investor didn't really understand the rental property business.

In February 2023, the Asahi Shimbun ran a feature that focused on the organizations that operate this kind of poverty business. One provided a consultancy for housing and employment that targeted indigent, elderly, and disabled people – demographic groups that landlords typically turn away. Anti-poverty support groups told the newspaper that in most cases the rental properties these organizations find are far from both the city center and the kind of employment opportunities underprivileged people rely on. Those who can work tend to be hired for part-time jobs and short-term positions. Given that there is relatively little work of that kind in the suburbs, they remain on welfare even if they can work. The rental properties realtors want to sell are usually located in the suburbs.

As a result of complaints about these organizations, a group of lawyers established a council to address the anaumeya businesses, both in terms of tenants who are exploited and investors who think they have been misled. The council planned to ask the welfare ministry to investigate the practice.

But the problem seems to be getting worse. A December article in Toyo Keizai said that anti-poverty groups reported that they had received five times as many complaints about poverty businesses from welfare recipients in 2023 than in 2022, and that some organizations have come up with new ways to gouge the people who seek their services. A common scheme is to advertise cheap rooms for welfare applicants with no money up front. However, when it comes time to signing a rental agreement, there may be all sorts of added fees for things like the purchase of furniture and appliances, as well as transportation charges incurred during the application process. One 59-year-old man told Toyo Keizai that even after moving into his rental unit and receiving welfare, he still had to go to charity outlets for free meals because all his welfare benefits went to the organization. What is particularly frustrating is that he was referred to this organization by a local government office. When he complained to the office, it told him it was his only option. The Toyo Keizai reporter, in a rare display of editorial pique, accused the authorities of ignoring their duty as public servants by cynically tossing needy citizens into the maw of the private sector, which they know will exploit them because that is in their nature. This attitude reinforces structural poverty by making it impossible for those at the bottom to work their way out of a perpetual cycle of debt and destitution. He added that he understood that welfare officials faced formidable problems, but said they weren’t even trying to solve them.

In a January essay for the blog site Magazine 9, anti-poverty activist Karin Amamiya discussed the evolution of poverty businesses, especially after the government suspended its special relief measures for needy individuals when the Covid pandemic officially ended. During the pandemic, welfare recipients were given free accommodations in underutilized hotels while they looked for work, but now they have been thrown back into the market, where they are prey to unscrupulous operators who know how to game the welfare system. As mentioned above, welfare officials are conditioned to be constantly alert to the possibility that applicants will take advantage of the system to avoid working. The irony is that, in fact, it is these so-called businesses that exploit the system for financial gain. Somewhere along the line, the government's public assistance priorities have become twisted.

Sources

Philip Brasor is a Tokyo-based writer who covers entertainment, the Japanese media, and money issues. He writes the Japan Media Watch column for the Number 1 Shimbun.