Issue:

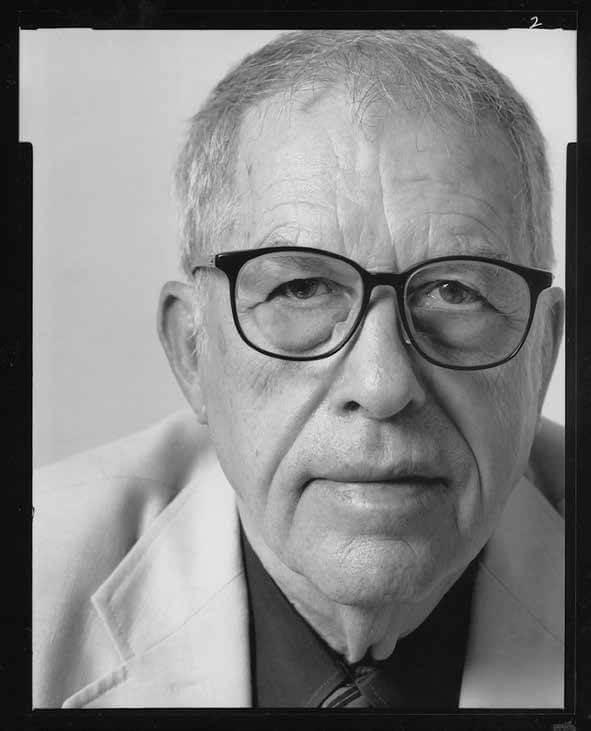

When Donald Richie passed away on Feb. 19 at age 88, he left behind enough books with his byline to fill a library shelf, innumerable articles on all manner of subjects penned for publications the world over and a global legacy of love for Japanese cinema, which he introduced to the world.

Equally impressive was his willingness to help others. As writers, photographers, editors and visitors to Japan of all professions and ages can attest, Donald was unstinting in sharing friendship, advice, assistance and introductions with anyone who needed them.

We asked friends and acquaintances to share, in turn, some of their memories.

John Howes, historian

Donald and I met on the General Blatchford, which was scheduled to arrive in Yokohama on Dec. 28, 1946 with 400 civilians to help run the Occupation. Donald was looking for adventure and very keen to get away from Ohio. We had departed the Brooklyn Navy Yard 50-some days earlier; engine trouble had made ours’ one of the longest passages ever. The ship sailed like a billiard table with no stabilizers, so most of the passengers physically shared in its lengthy struggle. En route, Donald, who was then 22, wrote a Christmas cantata for a choir that I was to conduct on the big day. We arrived in Naha on Christmas Eve, where there were few buildings standing; liquor, on the other hand, was everywhere around us. The resultant celebration left us with a cantata but no one sober enough to perform. And I don’t think it has even been performed to this day.

Martin Fackler, journalist

I didn’t know Donald very well, but one very brief glimpse into his character that I do recall was six or seven years ago at the FCCJ, when I asked him for his email in case I wanted to request an interview. He looked at me with an enigmatic smile and handed me his address his mailing address, that is in Ueno. He told me if I wanted to get in touch, the best thing was to write him a letter. Then after a pause, he explained that he thought cell phones and email had had the opposite of their intended effect: instead of linking people closer to together, he said they were actually isolating them and pushing them apart. Using the post office seemed to be his way of resisting this electronic atomization, or at least registering his lone protest against it.

Mark Schilling, film critic

One night at Donald’s apartment in Ueno, after dinner and a shared bottle of wine, the subject turned to his WWII service in the Merchant Marine, which I had always imagined as relatively uneventful. He told me, rather matter of factly, that he had three ships shot out from under him. When one ship started going down after being torpedoed in the Mediterranean, he said, “I jumped one way and everybody else jumped the other.” A German submarine surfaced and machine gunned his crewmates, while he stayed hidden on the other side of the ship. By the time it sank, the submarine had left and Donald, the only survivor, somehow made it to shore. He reminisced about the feeling of freedom he enjoyed, wandering the Italian countryside, alone. “I had the time of my life,” he said. I imagined Donald hoisted on the shoulders of brawny, cheering peasants, flowers garlanding his head.

Leza Lowitz, editor

Donald liked to stroll around Ueno park, where he lived for over two decades. As we circumambulated the lotus pond, he stopped to greet various people denizens of the demimonde or perhaps a rung lower on the social ladder people most others would walk by without noticing, or in fact, turn away from. Donald was fully present, fully observant. He saw them. They were real. We stopped at a small stand where you could make ceramic plates and bowls. We each made a plate. He painted his in a blue and white pointillist pattern, then he gave it to me. He elevated those who were with him by helping us to see the ordinary moments that make life extraordinary.

Leo Rubinfien, photographer

I was 15 when Donald formed the Tokyo Jane Austen Society with Seidensticker and my mother; I would visit him to talk about books and films. Wearing a vast hakama, he’d make waffles at his low table, insisting that no Westerner could ever become Japanese, that to think otherwise was dishonest. Decades later, however, wanting to demonstrate how much more adventurous he was than I, he took me to a shabby Okubo block full of women for hire, half of them Bolivian, dark and squat, half brightly lipsticked, Ukrainian, voluptuous. The police had stuck up warnings in Spanish and Cyrillic, and in the twilight eros mixed with gloom, it was a crazy scene. Donald was a connoisseur of backstreets, of course. This one was for sex, but he loved them all food alleys, lanes where you saw into rooms and lives, culsdesac with gods secreted at their ends. They were, perhaps, his imagination’s atelier. Now, suddenly, amid those women from Odessa and Cochabamba, a nation alistic stranger (Japanese) flamed at him resentfully, “What are you doing here? Go back to your own country!” Donald hesitated not half a second, but snapped back, “Kore wa boku no kuni dayo!”

Lesley Downer, author

Donald was wise and funny, also extremely mischievous. I first met Donald in the late 1980s. From then on, I saw him whenever I visited Japan, as well as at the London Film Festival, where he was treated with appropriate reverence. In 2008, we gathered in Tokyo to celebrate his 60th year in Japan. Donald gave us each a card with two photographs, one of him in 1948 in an overcoat, resting his elbow on the Nihonbashi bridge, the other 60 years later in the same pose, at exactly the same spot.

Gregory Starr, editor

In the early nineties, I was running excerpts from his then unpublished diaries in Tokyo Journal, and we would meet monthly for lunch at the FCCJ to discuss the next selection. The diaries were a mine of fascination, a ribald, unabashed, free flowing dissection of his life in Japan, as well as a detailed record of celebrity excess with him guiding world famous authors, artists, actors, filmmakers through Tokyo’s highlife and lowlifes. It was an astonishing history and Donald had gotten it all down, moments lofty and shocking and often unlikely to be appreciated by the subject of the entry. I would pore over the pages and come in with various suggestions. Very often, Donald would get that mischievous grin of a child on a prank, lean over and say, “He’s (or she’s) still alive. We’d better hold on to that one.” But the conversation would always lead to further detail, more stories and deeper insight laughter fueled tales of filmmakers, fellatio and philosophy over the starched white table cloths of the Club’s main dining room.

Alex Kerr, authorFrom my

September 21, 2009.

I carry my bag in the heat to Ueno park, and sit by the lotuses for a while as I call Donald about our lunch appointment but no answer. Finally I arrive at his door to find a note pinned on it. It says “Dear Alex, I’m sorry I can’t have lunch with you today. I’m having a heart attack. You can reach me at Jikei Idai Byoin. Regrets, D.” I jump in a taxi and go to the hospital, to find Donald, who’s in ICU, with Fumio. It’s serious (the doctor says it’s not a heart attack, it’s a stroke), but Donald pulls out his address book and gives me three numbers to call (Dae Jung, Gwen Robinson, and Paul McCarthy). I call them. Take Shinkansen to Kyoto.

Gwen Robinson, journalist

Donald cared greatly about his public image, not whether people liked him so much as whether they respected him. His real obsession was how he would be remembered. His aspiration to be a modern “renaissance man” clearly drove his forays into areas as diverse as painting, poetry, filmmaking and music composition. He always knew that his real talent lay in keen observations of people and society, like a contemporary Samuel Pepys, he once joked. He could only be such a chronicler, he told me, by being “in it but not of it,” never letting people get too close and shunning emotional commitments and cohabitation. “I chose the loneliest but by far the most rewarding path in life,” he added. No relationship ever threatened that philosophy. Even his long and genuinely affectionate relationship with his Korean partner in later years was a treasured liaison that nevertheless had its times and places. Over lunch at the Club two years ago, I asked him if he had any regrets about how he had lived his life. Smiling like a Cheshire cat, he answered slowly and clearly, “Well now, what do you think?”