Issue:

December 2024

Two infamous eccentrics whose actions put Ichigaya on the historical map

To anyone who has not yet done so, I would strongly advise that they arrange to take one of the morning or afternoon guided tours of the Ministry of Defense complex in Ichigaya, which include a visit to the Ichigaya Memorial Hall.

This is the remaining section of a once larger building, originally a military academy that later served as Japan’s equivalent of the Pentagon. Presently it houses the well-preserved room where the International Military Tribunal for the Far East was held.

Plenty of time is allotted to mingle with the old ghosts. Visitors are free to sit on the spectators' benches and shoot selfies in front of the dark wood dock where witnesses and defendants gave testimony, still complete with a ribbon microphone and red lightbulb used to signal interpretation in progress.

The room is partly devoted to rows of glass showcases displaying historical documents and objects related to the Memorial Hall, although explanatory notes are only in Japanese.

When indictments were read at the tribunal on May 3, 1946, the only civilian among the defendants was a tall, bespectacled 59-year-old man named Shumei Okawa, who happed to be seated directly behind former prime minister, army general Hideki Tojo.

As the clerk read the indictments, Okawa, clad in a pajama-like garment and wearing sandals, began squirming in his seat and chirping gibberish.

"... as the clerk reached count 22 of the indictment," wrote Eric Jaffe in his 2014 book A Curious Madness, Okawa rose halfway in his seat. Wearing what some reporters later called a 'cunning grin,' he extended his long arm forward with an open palm and slapped the top of Tojo Hideki's bald head. The startled general ... turned back to see [U.S. Army Colonel Aubrey] Kenworthy restraining Okawa by his gangly shoulder."

The incident was captured on film and can be viewed on YouTube.

After he slapped Tojo's head a second time, the court decided Okawa needed a psychiatric evaluation to determine his competence to stand trial. Based on a neurological examination and a Wasserman-Kahn blood test, major Daniel S. Jaffe, a U.S. army doctor assigned to the 97th Infantry Division, confirmed a Japanese doctor's earlier diagnosis that Okawa was exhibiting symptoms of tertiary syphilis.

Three months later, under heavy sedation, Okawa was committed to Matsuzawa Byoin, Japan's oldest mental hospital, in Tokyo's Setagaya Ward.

A native of Yamagata Prefecture, Okawa began his career from 1918 as a translator for the East Asian Research Bureau of the South Manchurian Railway Company. Within a decade he had risen to prominence in nationalist circles, stirring the political pot to the point that he came to be described by the allies as the "Japanese Goebbels".

As one of the ringleaders crusading for a "Showa Restoration," Okawa was involved in plotting and instigating the May 15, 1932 uprising, which culminated in the assassination of prime minister Tsuyoshi Inukai.

Hollywood actor Charlie Chaplin, who was visiting Japan at the time, was also targeted by the assassins, but avoided tragedy that day because he had been attending a sumo tournament in Ryogoku, escorted by Inukai's son.

Okawa was sentenced to 15 years for his part in the attempted coup, but the duration was reduced to seven years on appeal. Influential friends then pulled strings and he was released after only 16 months.

Just nine months after leaving prison he opened a boarding school, the Okawa Juku, to indoctrinate students with his political philosophy. Incredibly, his academy received generous funding and a stipend from the War and Foreign Affairs ministries. Three months before the war's end, a U.S. air raid reduced the school buildings to rubble.

The lone Japanese civilian defendant at the tribunal, Okawa was viewed as "the brain trust of Japanese militarism", described by a prosecuting attorney as "the sparkplug that kept the whole conspiracy alive and going over the whole period covered in the indictment".

An excerpt from the prosecution's 22-page dossier on him read: "Long before Tojo and his gang of international outlaws appeared on the scene, Dr. Okawa was busy night and day with his bloody coups and his evil determination for Japan to fulfill its Messianic Mission against an unwilling world."

"If Okawa had remained on trial," Jaffe speculated, "he would have been convicted with the others, and very well might have been hanged."

Okawa's syphilis was cured by a newly developed method previously used for treating malaria patients. He retired to write his memoirs and lived quietly until his death at age 71 in December 1957. He is buried adjacent to the Meguro Fudo temple in Tokyo.

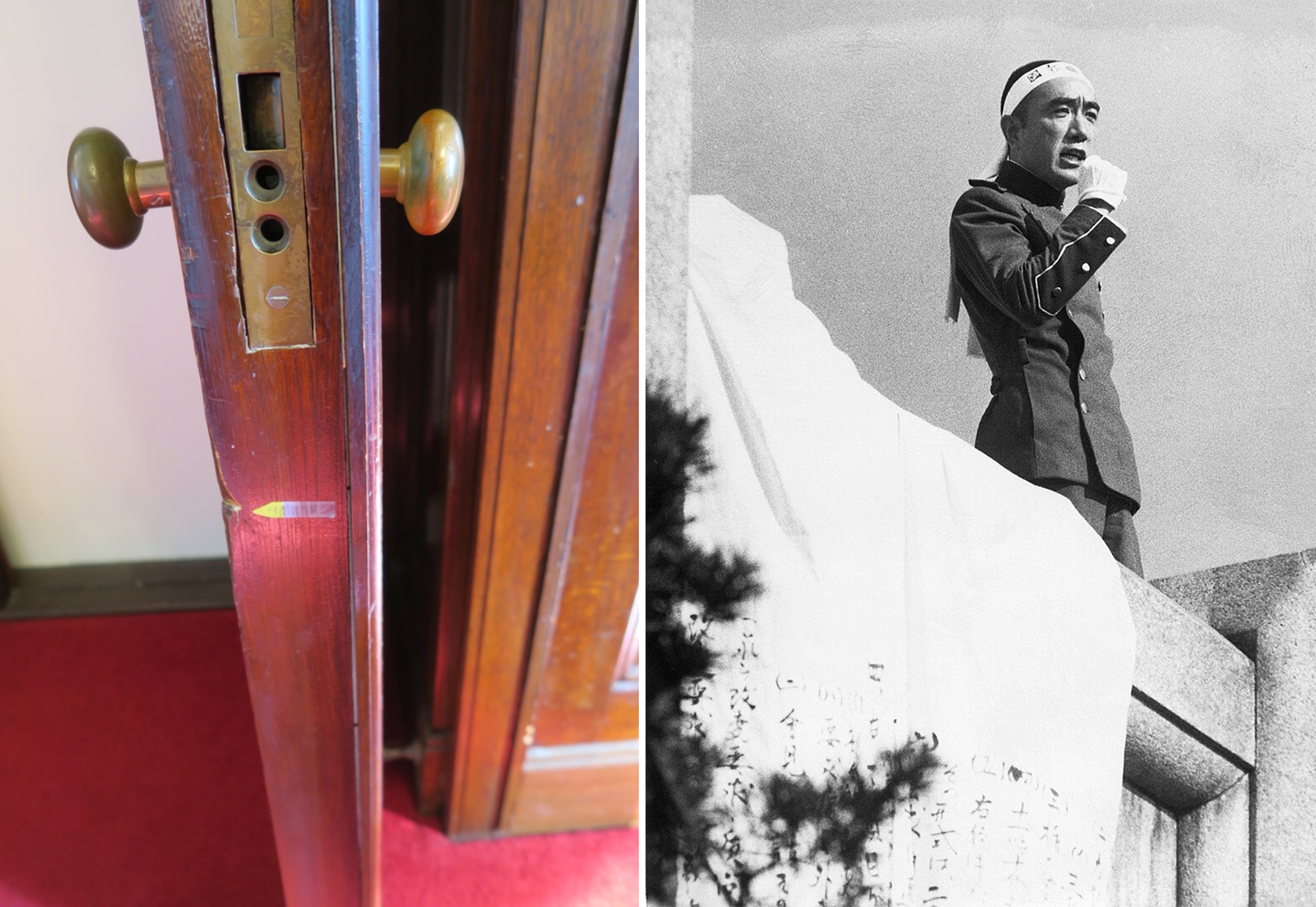

Returning to the Ichigaya Memorial Hall, our guide directs us to the second floor, which was once the office of the Ground Self-Defense Force commanding general. It was in this room on Wednesday, November 25, 1970, novelist Yukio Mishima and four members of his private mini-militia, the Tate-no-Kai (Shield Society) made a spectacularly unsuccessful attempt to goad GSDF soldiers into an uprising.

While the charismatic Mishima's writings were recognized as brilliant, his eccentric political views caused discomfort but were nonetheless politely tolerated. After all, he was an internationally recognized author, and almost a certain shoo-in for a future Nobel Prize for Literature. By toadying up to Mishima, the GSDF perhaps sought favorable press coverage. Nonetheless it seems reasonable to question its lax attitude toward security, admitting five uniformed members of a patriotic paramilitary group, concealing real swords, into the commanding general's office. What could possibly go wrong?

On the morning of November 25, 1970, Mishima submitted the manuscript for the final part of his tetralogy Hojo no umi (translated as The Sea of Fertility) to his editor and set off on his rendezvous with fate.

At 11:15 a.m., Mishima and his uniformed underlings, clad in their snazzy uniforms, were admitted to General Mashita's office. The stocky Mashita, a judo expert, bowed, welcoming his visitors.

Suddenly, at a prearranged signal, the five men pulled short swords from beneath their uniforms and pounced on the general, gagging him and tying him to a chair. Three of Mashita's unarmed subordinates rushed in to attempt a rescue and a brief melee ensued, but they were driven from the room by the sword-wielding minions, who then shifted a heavy desk to barricade the door.

Mishima stood before the trussed-up Gen. Mashita and demanded he summon all the men in his camp to hear him speak.

Wearing a hachimaki headband emblazoned with a patriotic slogan, he unveiled a zany six-part manifesto, handwritten on a large white sheet, that he draped from the balustrade. He then began haranguing some 1,200 soldiers assembled below.

"Listen to me carefully, very carefully," he shouted, "I've come here with a feeling of sadness and indignation, Japan’s politics have been marked only by intrigues…

"Can you not see this logic? You have been degraded into nothing but a mere protection of the present Constitution, a Constitution that makes your very existence illegal" – a reference to Article 9, banning the maintenance of armed forces.

Not the least bit persuaded, the soldiers began heckling Mishima with a cacophony of catcalls and jeers.

After 10 minutes of getting nowhere, Mishima realized the futility of his quest. He bellowed "Tennoheika, banzai! (long live the Emperor)” and went back into the building.

At around 12:40 p.m., the final act began as Mishima stripped to the waist and knelt on the red carpet directly in front of Gen. Mashita. Sensing that Mishima was preparing to commit seppuku, the general frantically begged the novelist not to go through with it. Mishima ignored him, and gripping a short sword, he issued a loud shout and plunged the sword into his abdomen.

Mishima's kaishakunin, 25-year-old Masakatsu Morita, who was also rumored to be his lover, swung the sword but failed to behead Mishima. After two more failed attempts, Hiroyasu Koga, a former kendo champion, stepped in and completed the job. Morita then attempted to perform seppuku himself but botched that as well, and giving up, he gave the signal and Koga beheaded him as well.

Members of nationalist groups praised Mishima's death, calling it an "action for justice". The nation's politicians, however, issued limp denunciations.

"I can only think they went mad," Prime Minister Eisaku Sato wrote in his diary. Future prime minister Yasuhiro Nakasone, then director-general of the Japan Defense Agency, criticized the action at a news conference, saying, "It's a terrible nuisance. What they did is so aberrant. I always regarded Mishima as a man of common sense."

"It was a wasteful way to die," said Nobel laureate Yasunari Kawabata, Mishima's patron and the go-between in his marriage, while wiping away tears.

The New York Times reported that the police had put extra guards on duty to protect senior government officials and political leaders and quoted an unnamed police official assigned to monitor right-wing organizations as saying: "It is this period immediately after a sensational incident that we are most worried about. People are shocked and excited, and they may do foolish things."

Two weeks later, a three-page article by Jerrold Schecter titled “The Samurai Who Committed Hara–Kiri" appeared in Life magazine's issue of December 11, 1970.

At the time of his death at age 45, Mishima had authored 34 novels, approximately 50 plays and 25 books of short stories, more than 35 books of essays, a libretto and one film.

In retrospect, it became apparent that Mishima had meticulously planned his suicide over a year in advance, going so far as to leave behind funds earmarked for the legal defense of the three surviving members of his group.

It's also clear that Mishima had long harbored a preoccupation with ritualized death. In 1961 he published a short story titled Yukoku (Patriotism), about a young army officer who commits seppuku after the failure of the February 26, 1936, coup attempt that he had supported. Mishima directed the eponymous film and starred in the lead role.

Five years later, while speaking before the FCCJ, on April 18, 1966, Mishima told his audience: "I cannot believe in western sincerity because it is invisible, but in feudal times we believed that sincerity 'resided' in our entrails, and, if we needed to show our sincerity, we had to cut our bellies and take out our visible sincerity."

Mishima was 20 years old on August 15, 1945, when Emperor Showa broadcast Japan's surrender. His diary entry on that day read: "Only by preserving Japanese irrationality will we be able contribute to world culture 100 years from now."

Perhaps it was from this time that the seeds of his self-destruction first began to germinate.

Mark Schreiber is author of Shocking Crimes of Postwar Japan (Yenbooks, 1996) and The Dark Side: Infamous Japanese Crimes and Criminals (Kodansha International, 2001).