Issue:

Beyond the Nobels

Japan has a number of coveted international prizes in science and technology, some of them created by well-known business figures.

by JERRY MATSUMURA

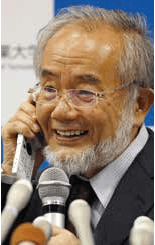

On Monday, Oct. 3, news headlines datelined Stockholm reported that Japanese biologist Yoshinori Ohsumi, 71, a professor at the Tokyo Institute of Technology, had won the Nobel Prize in medicine for discoveries on how cells break down and recycle content, a garbage disposal system that scientists hope to harness in the fight against cancer, Alzheimer’s and other diseases.

He was the 25th Japanese Nobel Prize winner since 1949, when Dr. Hideki Yukawa, a physicist, received the first Nobel Prize to be awarded to a Japanese citizen, “for his prediction of the existence of mesons (a subatomic particle) on the basis of theoretical work on nuclear forces.”

The greater part of the Japanese public was not even aware of the prize at the time though citizens were not prohibited to receive it, unlike in Hitler’s Germany. But coming so soon after their disastrous defeat in World War II, Yukawa’s international recognition gave the Japanese particular pride and encouragement.

Now Japan is not only in the top league of Nobel Prize recipients (in the field of natural science, the number of winners has been second behind the U.S.), but it also issues a number of international prizes which offer major incentives for the world’s most talented scholars and researchers. In fact, where Japanese awards and Nobel Prizes cover the same categories, it is often the case that outstanding merit is recognized first in the awarding of a Japanese prize. (In 2012, for example, Professor Ohsumi won the Kyoto Prize, one of Japan’s top private awards for global achievement.)

Out of a total of some 600 science and technology prizes, there are four at the top based on financial value. This does not necessarily mean that they have the greatest significance, let alone that the amount of prize money or the order represents the degree of importance or recognition. As with Nobel Prizes, nominations are sought from around the world.

THE KYOTO PRIZE WAS started in 1985 by the Inamori Foundation in Kyoto, founded in the previous year by Kazuo Inamori, the founder and Chairman Emeritus of Kyocera Corporation, with his personal funds. Three annual prizes of ¥50 million are awarded to outstanding individuals or groups in the categories of Advanced Technology, Basic Sciences, and Arts and Philosophy. Particularly characteristic of The Kyoto Prize is the Arts and Philosophy category, indicating the importance Inamori attaches to the enrichment and elevation of the human spirit that is lagging very much behind the progress in science and technology.

Nine of the past Kyoto Prize recipients have gone on to receive the Nobel Prize, including South Africa’s Dr. Sydney Brenner, who made significant contributions to work on the genetic code and Dr. Jack Kilby of the U.S., the coinventor of the integrated circuit.

The Japan Prize has been awarded annually since 1985 by the Science and Technology Foundation of Japan (renamed as the Japan Prize Foundation in 2010). The foundation was created in response to the government’s wish for a prestigious international prize of the Nobel Prize class to be issued locally. It was largely funded from a personal donation from the late Konosuke Matsushita, the founder of the Matsushita Electric Industrial Co., Ltd. (now the Panasonic Corporation) “to honor scientists who have made original and outstanding accomplishments in science and technology with significant contributions made to peace and prosperity of mankind.” A cash prize of ¥50 million is awarded to individuals in two fields each year. Since its launch, the Emperor and Empress have associated themselves with the award through their presence at the Prize Presentation Ceremony.

Six of the Japan Prize awardees have subsequently been awarded the Nobel Prize, including Dr. Gerhard Ertl of Germany, whose research laid the foundation of modern surface chemistry, paving the way for the development of cleaner energy sources. He was awarded the Japan Prize in 1992 and the Nobel Prize in 2007.

The Blue Planet Prize is an annual prize established in 1992, the year of the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro, by the Asahi Glass Foundation. Each of the two recipients (individuals or organiza tions) who have made outstanding scientific contributions to promoting solutions to global environmental problems receives a monetary award of ¥50 million.

The International Cosmos Prize is an annual prize with a monetary value of ¥40 million. It was created in 1993 by the Expo ’90 Foundation to commemorate the 1990 Osaka International Garden and Greenery Exposition, whose theme was “The Harmonious Coexistence between Nature and Mankind.” It rewards an individual or an entity making an outstanding contribution to environmental science and research as well as to other fields promoting this goal.

THE FIRST TWO PRIZES the Kyoto Prize and Japan Prize share a number of features in common. Each was founded with the personal funds of the industrialists concerned. And, in both cases, the founder had built up his business from modest beginnings, suggesting they both shared a desire to repay society.

Inamori, who founded the Kyoto Prize, is a dynamic, charismatic entrepreneur who founded a small ceramics company and built it into the Kyocera Corporation, the world’s leading hightech ceramic and electronic products company. He is also the founder of DDI, the first long distance telephone company to challenge Japan’s telecommunications monopoly, and in 2010 was appointed chairman of the then bankrupt Japan Airlines at the pleading of the Japanese government.

Born in 1932, Inamori battled disease and various family problems as a youth. In 1955, immediately after graduating from Kagoshima University, where he majored in applied chemistry, he joined a small insulator company in Kyoto after being rejected by other larger companies. In 1959, he left this company to start up a tiny operation of his own, enduring all manner of hardships before eventually building up a large personal fortune.

He reportedly regards his hardwon wealth as something entrusted to him to administer for the benefit of humanity. Of the Kyoto Prize he wrote: “I first conceived the idea of the Kyoto Prize in 1984, when Kyocera celebrated the twenty fifth anniversary of its foundation. At the time I was fifty two years old. I wanted to bring to life the concept that a human being has no higher calling than to strive for the greater good of humanity and the world. . . .”

Inamori, who has shown genuine interest in the spiritual dimension from his youth has now moved beyond the business world to become, as it were, a public philosopher of modern Japan, teaching his people centered philosophy of management to groups of young business managers and entrepreneurs in various regions of the country, and writing books on management and on the meaning of life. In one of his books, A Compass to Fulfillment: Passion and Spirituality in Life and Business, he stresses that man’s soul is immortal and that the enrichment and elevation of the human spirit, or “the care and improvement of our soul” in Socratic terms, is the most important task in one’s life. His company’s motto is: “Respect the Divine and Love People.”

JAPAN’S TOP PRIZES

Kyoto Prize: www.inamori-f.or.jp

Japan Prize: www.japanprize.jp

Blue Planet Prize: www.af-info.or.jp

International Cosmos Prize: www.expo-cosmos.or.jp

THE LATE KONOSUKE MATSUSHITA (1894-1989), who founded The Japan Prize, was Japan’s most successful postwar businessman and one of the most inspirational role models of all time, particularly during Japan’s high growth period. Born into a poor farming family, Matsushita worked at various manual jobs from the age of nine before opening a small one room electrical parts factory in Osaka in 1918.

Always in search of innovation, he developed a series of home electrical appliances and pushed his company to the forefront of the industry. His accomplishments as leader, author, educator, philanthropist and management innovator are astonishing, and his philanthropy accelerated as he aged. In 1979 he established the Matsushita Institute of Government and Management (MIGM), designed to develop and promote leadership for the 21st century. Yoshihiko Noda, the former prime minister, was among the first of its graduates.

The Japan Prize, which was established four years before Matsushita’s death at 94, was “intended to honor scientists, of whatever nationality, whose research has made a substantial contribution to the attainment of a greater degree of prosperity for mankind.” His philosophy, however, was not a science centered one, but envisioned peace, happiness and prosperity coming from open minded people with humanistic values who had the courage to tackle society’s most intractable problems. The Showa period came to a definitive end in 1989, as it marked the deaths of both Emperor Hirohito and Matsushita.

Opposite, the Kyoto Prize medal; left, Yoshinori Ohsumi at a press conference after winning the Nobel Prize in medicine this year (and who won a Kyoto Prize in 2012); above, the 2016 ceremony for the Japan Prize winners attended by the imperial couple

While the Nobel Prizes, of course, remain the most coveted of the world’s awards in the scientific and other fields, Japan’s prizes are attracting growing interest from researchers all over the world. And these prizes not only benefit the winners, but also draw attention to Japan’s commitment to great advances in science and technology.

Kosuke “Jerry” Matsumura is a freelance journalist based in Tokyo, formerly affiliated with Hugo Publications in London.