Issue:

From enemy combatants to saints, architects and celebrities, this small Tohoku city seems to have stumbled upon a magic formula for survival in a time of need.

Deep suffering can never be measured or compared, particularly in regard to tragedies of the dimensions that struck Tohoku on March 11, 2011. But it’s hard to ignore the fact that the notoriously unruly gods of the region spared little that day, and the town of Onagawa’s suffering was conspicuous in its scope. Its core was snuggled tightly in a narrow corridor between sea and hills, so when the 14.8 meter wall of water (some witnesses believe it hit nearly 20 meters at its peak) swept over the town, it leveled 70 percent of its buildings, stripped the town of its railway and took the lives of nearly 10 percent of the population in one fleeting sweep.

That the gods targeted Onagawa at all seems cruel. The proud, ancient enclave was already in the throes of both an economic and population freefall. Voting down a 2005 initiative to join six other towns in a merger that would make Ishinomaki city the second largest in Miyagi Prefecture along the way, Onagawa’s population had dropped from 16,000 in 1980 to 10,000 in 2010.

Neitzsche could well have been looking at Onagawa when he famously observed “that which does not kill us, makes us stronger.” Onagawans appear to have an abundance of that stubborn and resilient DNA which gives some trauma survivors the positive boost that psychologists call “post trauma growth.”

Soon after the disaster, the members of the “Town Building Study Group,” formed only the year before by the town’s businesses and young entrepreneurs to take urgent economyboosting action, were promptly out on reconnaissance, vigorously mapping the still operational components of the town.

The results were immediate and dramatic. One week later, construction hands in Onagawa had cleared enough to open a narrow path for supply deliveries and SDF access while volunteers and rescue workers were reporting from Ishinomaki that debris-clogged roads made that town largely impenetrable. “Let no crane or standing facility be left idle” became the town’s battle cry.

“The earthquake may well have been the jolt which snapped us out of the old complacency and mindset that were killing our town,” says Yoshihide Abe, CEO of Umemaru Newspapers, a delivery service. Abe resumed newspaper delivery in just three days, and his extensive dealings with local businesses helped gather leaders to form an action group focused on reconstruction.

The president of a fish products manufacturer, Masanori Takahashi, provided his still-intact facilities for meetings, and on his premises promptly built offices for the chamber of commerce, tourist association and fish processing associations to resume the much-needed operations of the town’s core businesses. By mid-April, the Reconstruction Coordination Association was up and running to work with the not-yet fully operational municipal government.

The flyboy . . .

In the midst of the frenetic aftermath, mysterious funds started to appear and not just vague offers of assistance, or promises languishing in the corridors of Japanese aid agencies awaiting distribution. The funds were, for the most part, free from the clutches of the disaster relief Black Hole because they were earmarked specifically for the “The People of Onagawa.”

The town was moved and thoroughly perplexed by the gifts, arriving in large part from Canada. Only a few elders had any inkling as to the possible roots of such generosity.

The funds were followed by the tread of Canadian feet on the ground, in the form of droves of volunteers with dollops of cash in hand from family and friends, and the reason was quickly apparent. It seemed that a city of 10,000 in British Columbia called Nelson had a particularly strong resonance with the tragedy, a feeling that was reinforced after the local Canadian children folded thousands of origami cranes to raise funds, matched by the city. Their generosity soon arrived in Onagawa as a $40,000 gift.

What the citizens of Nelson recalled, though largely forgotten in the mist of Japan’s collective WWII amnesia, was the memory of one Hampton Gray that echoed from deep beneath the waters of Onagawa Bay.

Hampton (or “Hammy,” as he was known to family and friends in his hometown of Nelson) was the most decorated Canadian pilot of WWII. He had joined the Royal Navy in 1940 and fought throughout the rest of the war in such locations as Africa and Norway before joining the attack on Okinawa and mainland Japan.

On August 9, 1945, less than a week prior to Japan’s surrender, Gray was leading an air attack on the escort ship Amakusa, part of the naval fleet in Onagawa harbor. Though he sunk the ship, he took fire from five naval batteries as well as from the shore, and was last witnessed by his fellow flight members rolling right in a ball of fire and smoke, and exploding into the waves of the bay. For his heroics, he posthumously received the Victoria Cross, one of only two members of the Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm to be so decorated.

It was hardly an event, one would think, that would inspire great friendship between nations, particularly as there was also considerable collateral damage to civilians on shore. But, after the war, Canada persevered in delicate negotiations to convince Onagawa to help locate their favorite son’s Corsair and remains. When joint recovery operations proved futile due to mines left from the war, Canada then asked the people of Onagawa to permit the construction of a memorial to their fallen hero. Preferably with a view, no less.

Quite understandably, this was cause for considerable discussion and division in the town, but when the memorial was eventually erected in 1989, its opening was attended by inter-national media and Canadian dignitaries and even some survivors of Amakusa. A local Lion’s Club pledged to main-tain it in perpetuity as a sym-bol of enduring friendship. One current executive of the Club, Tadao Kato, remains humbled by the enormity of the respon-sibility entrusted in his generation, particularly as the fate of their chapter was much in the doubt on the day of the earth quake and tidal wave.

“A friendship nurtured in such calamity is important and of deep value”

That pledge has since blossomed into a formidable bridge linking the small town with the outside world. Perhaps it is a symbolic one, but it comes with enormous practical ramifications for recovery that the town would be ill-advised to ignore. The channel of communications with the Canadian Embassy in Tokyo and Navy remain particularly strong. And though the memorial stone toppled and broke on that day in March, 2011, it has since found a new home by a hospital on a hill with, of course, a view.

The thespian . . .

“We knew about the memorial as children,” recalls Masatoshi Nakamura, the renowned actor and singer who hails from Onagawa. “Older people in town used to talk about an air raid in WWII, but my post-war generation knew little about the story behind the Gray memorial. So the way Canada reached out to us certainly fills us all with gratitude and hope.”

Onagawa is lucky to have a celebrity spokesman like Nakamura, who himself lost three cousins and his childhood home to the tsunami. He campaigns tirelessly at schools and charity events to keep Onagawa in the thoughts of people, lest anyone forget that Tohoku’s struggles continue.

He also is a sort of bridge, thanks to his starring role in American Pastime, a 2007 U.S. film about baseball in a Japanese internment camp. Nakamura was surprised by the unexpected speed and generosity with which former crew and cast members orchestrated donations that he says “just kept coming!”

Onagawa’s international bonds were once more on prominent display after stories began to circulate about how the local fish-processing company executive Mitsuru Sato was swept away by the tsunami after leading the Chinese trainees working at his firm to safe ground. Sato instantly became a virtual patron saint to millions in China and Hong Kong, prompting visiting Chinese Premier Wen Jiabao at the time to request a pilgrimage to Tohoku in honor of the “brave man who transcended nationality” to save his countrymen. Sato’s portrait can still be seen proudly displayed in Dalian, from where the majority of trainees living in Onagawa at the time hailed.

The architect

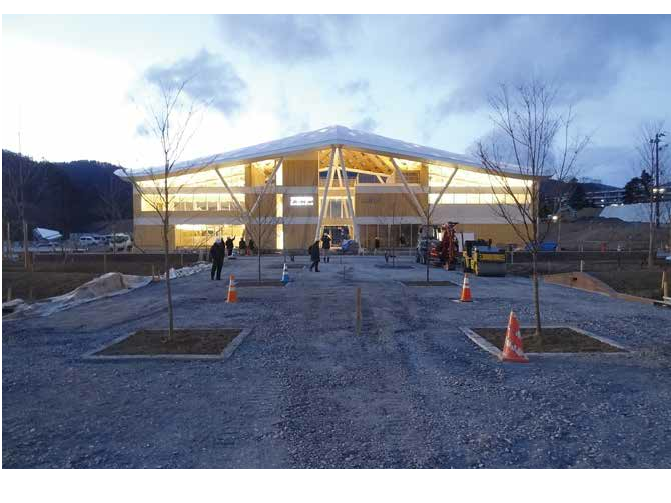

Now, as the town prepares to celebrate a recovery milestone with the completion of the Ishinomaki Line’s last few miles into the center of town on March 21, Mayor Yoshiaki Suda gleefully senses a great buzz around Pritzker-winning architect Shigeru Ban’s new station building. Ban, who is as well known as a humanitarian visionary as a pioneering architect possessing a magic touch with unusual materials, was much feted for the many emergency structures he created for Tohoku as well as for the ergonomic paper partitions his Voluntary Architects’ Network installed pro bono to give Onagawa and other towns’ evacuees a modicum of much appreciated privacy in the crowded evacuation centers.

The station building is a commission that the mayor himself a happy resident of Ban’s pro bono temporary housing since the tsunami feels “is not only a reflection of Ban’s exceptional talent, but one which brings his stature and international interest to the town.” He goes on to add, “The publicity certainly won’t hurt.”

“I’m happy and honored to be a part of the station reopen-ing,” says Ban, “and I hope it provides a little respite for tired travelers, even though they may not come in large numbers at first.”

Modest projections all around, but everywhere the excitement is palpable. The town is already looking forward to the next phase of Onagawa Station construction that will include a new shopping promenade and a park. Kato, the keeper of the flame from the Lions Club, is already contemplating the possibility that Hampton Gray’s memorial may one day find a more visible resting place in the new plaza, so that many more can pay their respects.

“A friendship nurtured in such calamity is important and of deep value,” said Premier Wen Jiabao that fateful year when all seemed lost. He could have been speaking for the entire world, which luckily for Onagawa, continues to watch . . . and care.

Mary Corbett is a writer and documentary producer based in Tokyo.